The importance of education

For Luther and the reformers, as for the 16th century humanists, it was the duty of parents and of the Churches to give schooling to children. This duty had been an essential component of the French Reformed Churches’ code since their 1578 national synod held in Sainte-Foy.

The Edict of Nantes allowed members of the so-called ‘So-called Reformed Religion’ to run their own schools, but only in places set aside by the same Edict for services of worship.

The « small schools »

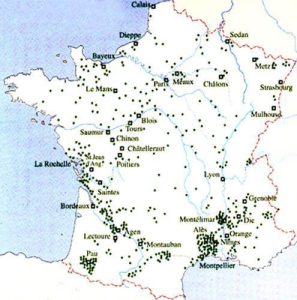

As a rule, each Reformed Church set up its own school : in most cases a primary school for boys, but often also primary schools for girls or mixed schools.

The schoolmaster or regent was recruited by the presbytery from each Church, the latter providing accommodation and a small salary. This was increased by a contribution paid by the parents (school fees).

The teaching was on an individual basis : each pupil would come up in turn to read, write or recite at the schoolmaster’s desk. The only common activities were psalm-singing and catechism.

The Colleges

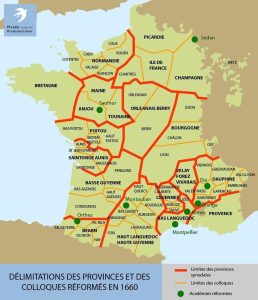

At the beginning of the 17th century, there were about thirty Reformed colleges (the 1596 national synod of Saumur had stipulated that there should be at least one college for each provincial synod).

At college, a pupil at first studied Latin, then Greek, with history, dialectics and rhetoric in the last two classes.

The day began and ended with prayer while catechism formed part of the school curriculum. The schoolmasters took the pupils to hear the Sunday sermon.

The colleges were run by a headmaster selected as much for his spiritual qualities as for his administrative and teaching abilities. The masters and teachers all had to sign the confession of faith and the church code of the Reformed Churches (a decision taken at the 1620 national synod of Alès).

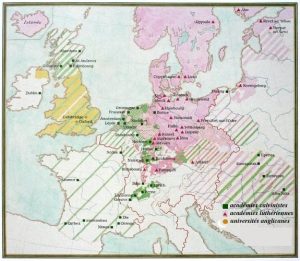

The Academies

The term Academy described a college which had been upgraded to become a teaching centre of university level and including a faculty of theology, on the Geneva model.

After a two years course consisting mainly of philosophy and leading to a Master of Arts degree, the student could go on for a three years course in theology. The study of Hebrew, Greek, grammar and rhetoric led to a thorough study of the texts.

A student thus acquired a sound basis in theology, necessary to a « minister of the word of God », whose « main duty was to preach ».

The primary aim of the Reformed Churches was to train future ministers. But some academies, for instance those of Orthez and Sedan also offered courses in other subjects, such as law or medicine,

The Academy was headed by a rector who often taught as well – he was appointed for one or possibly two years and could be re-elected.

The synods were responsible for financing university education.

At the 1620 synod of Alès, the academies of Die, Montauban, Nîmes, Saumur and Sedan were officially established.

Protestant teaching methods

Although religion was considered to be the main aim of Academy teaching, it was also possible to thoroughly study classics.

Both Protestant colleges and Catholic ones – such as Jesuit or Oratorian – gave great importance to studies with a humanist orientation.

At times, the same school books and exercises were used by both.

But some differences must be mentioned :

- the wider choice of authors from the classics in Protestant schools ;

- the far greater importance given to biblical texts in the studies of a protestant academy ;

- and especially, the Protestants taught Greek, Hebrew and Latin, whereas the Jesuits taught Latin but little else in the way of languages ;

- Catholic colleges were all run on the same pattern, whereas each Protestant academy and college had its autonomous organisation.

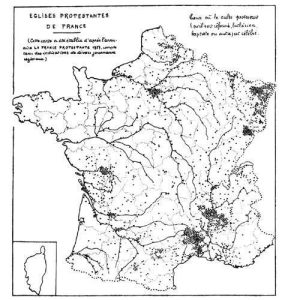

The Protestant network of academies was gradually dismantled by the State

From 1661 onwards, both the State and the Catholic Church tried to regain control of education in France.

All along the 17th century, various measures were adopted with a view to curtailing the development of Protestant primary schools and colleges. Mixed schools were closed down on moral grounds and if a Protestant Church was no longer in use, its school was closed down with it. The Jesuits would take over the previously Protestant schools.

As for the Academies, measures were taken to drain them of any financial means and their teachers were prohibited from attending synod meetings.

They were destroyed one after the other : Nîmes in 1664, Sedan in 1681, Die in 1684, Saumur and Montauban in 1685. The Academy of Montauban had already been transferred to Puylaurens in 1659.

The result of all this was that many gifted intellectuals fled to the countries which would later be known as the Refuge countries. Many of them were to play an important role in the development of the host country, such as Pierre Jurieu or Pierre Bayle in the Netherlands.