Peter Waldo (1140-1217)

The Waldesian movement took it’s name from Valdus or Waldo who, around 1170, following a crisis of conscience, sold his possessions and spent the rest of his life preaching the Gospel to his fellow men. To help the non-clergy understand the New Testament he had it translated into the language which was commonly used at that time, Provencal. His ideas spread all over Europe. Waldo and his disciples, “the Poor of Lyon“, were declared heretics by the Roman Catholic Church, mostly because in their community lay people, including women, were allowed to preach. They were excommunicated by Pope Lucius III in 1184.

Nevertheless, the “Poor of Lyons” continued to preach, but they were forced to lead underground lives because they were persecuted. Their main source of inspiration was the Sermon on the Mount. They advocated non-violence and refused to swear oaths, while also rejecting any compromise by the Church with those having political power.

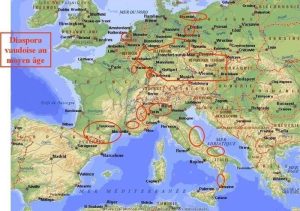

The Waldensian movement (as they came to be called by their enemies) grew from strength to strength during the Middle Ages, in spite of persecution. In the 18th century it was based in Lombardy, around Milan. Later it spread to Austria and Southern Germany, where it was strongly influenced by the followers of Jan Hus. Large communities also became established in the Piedmont valleys. Their preachers, called “barbes” (i.e. “uncles”, so as not to be confused with the Catholic “fathers”) travelled throughout Europe regularly visit the small underground groups of followers.

In the 16th century they joined with the Reform Movement

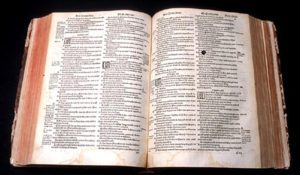

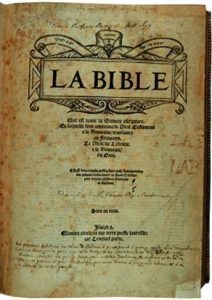

When the Reform Movement spread throughout Europe, the Waldensians came to hear of it and decided they wanted to know more about this new Church movement. They sent envoys to Berne, Basel and Strasbourg to hold discussions with Oecolampadius, Martin Bucer and William Farel, who was later present at the 1532 Waldensian synod in Chanforan (in the Waldensian Valleys of Italy). After several days of discussions, the Waldensians decided to join the Reform Movement and, in particular, to become followers of Zwingli and Bucer. They came out into the open, to a large extent but, from then on refused to follow any Roman Catholic practices, built new “temples” and held services in public. Their pastors were attached to a particular parish and no longer travelling preachers or “barbes”, as in the Middle Ages. They financed the translation into French of the entire Bible ; this was the well-known Olivetan Bible.

The Reform Movement spread throughout Italy (1532-1559)

After the synod of Chanforan in 1532, the Waldesians were active in spreading the ideas of the Reformation in Italy, first down on the plain and then to the south of the peninsula, thus linking up with other existing groups in Italy which had already joined the Reform Movement.

Evangelising of the Piedmont Valleys took place primarily during the French occupation, from 1536 to 1559 (the Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis gave back to the Duke of Savoy his former territory). Many inhabitants of the Piedmont Valleys went to Geneva for religious instruction and returned to preach the Gospel throughout the Italian peninsula. From 1555 onwards, the first “temples” were built.

The Waldensians suffered violent repression after coming out into the open ; in this they shared the same fate as the French Protestants. At first, the victims were the pastors, owners of bookshops and leaders of the movement. Many were burned at the stake for their faith.

The main groups of Waldensians were based in three regions : Provence, Calabria and the Alps. All suffered from persecution at one time or another.

The massacre of the Waldensians in the Luberon

In the 14th and 15th centuries, waves of Waldensians left the Dauphiné (Southeastern France) and Piedmont Valleys to settle in Provence, where they helped to revive a region which had seen ruin and depopulation. They were, on the whole, well accepted. In 1532, there were about thirty “barbes” in the Luberon. But as soon as they supported the Reform Movement they were victims of persecution by the famous leader of the Inquisition, Jean de Roma, and Baron Jean Meynier d’Oppède, first President of the Parliament of Provence at Aix. The “Arrêt de Mérindol” of 1540, ordered the complete destruction of the village , although this did not actually take place until 1545. Mérindol was plundered and destroyed by Baron Meynier d’Oppède’s troops. Most of the inhabitants were able to flee and later returned. The massacre spread throughout the Luberon and there were more than 2000 victims. 700 Waldesians were sent to the galleys. This massacre of the Waldensians shocked the whole of Europe and was never forgotten in the area.

The Provencal group, which had been almost entirely destroyed, was soon absorbed into the French Protestant movement and all but forgot their Waldensian roots.

The massacre of the Waldensians in Calabria

There were many groups of Waldensians in Calabria. After the synod of Chanforan they joined the Reform movement and came out of hiding. The Inquisition sent a mission to this part of Italy in 1560 with it’s attendant courts and punishment at the stake. Two pastors who died for their faith have never been forgotten – Jacques Bonello and Giovanni Luigi Pascale – who had both been sent to Calabria by the Church in Geneva. One was burned at the stake in Palermo in 1560 and the other in Rome in the same year. The country was then ravaged by a violent military campaign and the Waldensians were decimated ; those who escaped were forced to renounce their faith.

Waldensian resistance in the Piedmont Valleys

In the Cottian Alps the Waldensians lived both in the Dauphine and in the Duchy of Savoy, on either side of the mountain. In the Dauphine, the Waldensians joined the French Protestants, took part in the religious wars and then lived under the somewhat modest protection of the Edict of Nantes ; they managed, however, to keep in regular contact with the other Waldesians in the Duchy of Savoy.

Although the valleys on the Italian side of the Alps belonged to the Duchy of Savoy, they were in constant fear of invasion by France. After the first French occupation lasting from 1536 to 1559, Duke Emmanuel Philibert, who had regained his land with the treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis (1559), sent a military expedition in 1560 against the Waldensians in the Luserne valley. Their preachers persuaded them to give up their traditional non-violence and take up arms. They fought up in the mountains and for them it was truly a holy war, like the fight between David and Goliath. Before every battle, the soldiers would pray and sing psalms, while their pastors maintained strict discipline among the troops and forbade any looting. The Dauphine Protestants sent military support from the other side of the Alps and the Waldensians were able to make a stand against the Duke’s armies. After six months of fighting, he agreed to sign a treaty. The Cavour agreement (1581) brought back the special privileges and exemptions which the Waldensians had previously been given and it became possible once more to worship in public even in remote places in the mountains. Under this agreement, a Roman Catholic prince had to allow spiritual dissidents the right to live on his lands. However, sadly, this treaty resulted in the Waldensians having to retreat back to the mountains, and stopped their spread on the plain. The adjective “Waldensian” (or “Vaudois”), from then on, was only applied to that tiny remnant of the former Waldensian diaspora.

The 17th century was a time of hardship and struggle

In 1630 an epidemic of the plague came to the Waldensian valleys and destroyed a third of the population – 11 out of the 13 pastors died. The Waldesians sent envoys to Geneva to ask for help and pastors were sent from Switzerland. These pastors made the Waldensians accept the customs of the Church of Geneva and they had to adopt French as the official language of their Church – this situation did not change until the mid 19th century.

The Turin court was under the political influence of the French. From 1640 onwards the Waldensians came under attack more and more frequently. In 1655 troops were stationed with Waldensian families and began to massacre the population. The Protestant valleys of the Piedmont became Roman Catholic once more. These massacres, known as the “Piedmont Easter massacre” or the “Bloody Spring” aroused indignation in Cromwell’s England. It also prompted the poet John Milton to describe the massacres in a famous poem. Holland and in the rest of Europe were deeply shocked at such cruelty. Mazarin himself intervened. At the same time guerilla warfare continued in the Piedmont Valleys, fought by a handful of indomitable soldiers led by a farmer, Janavel, who is a legend in Waldensian history. Due to international pressure, the Duke of Savoy had to give in and abide by the conditions of the Cavour agreement. The Waldensians were able to go back to their valleys but the Duke put more and more pressure on them as time went by.

In 1685 the effects of the Edict of Nantes were also felt in the French territory of the Piedmont Valleys : Le Val Plagela and the Val Cluson. Consequently, many Waldensian families decided to go into exile and settled in Hesse-Cassel, founding villages where they had freedom of conscience and could live in accordance with their faith.

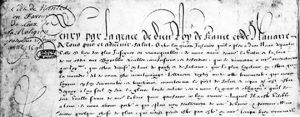

The Duke of Savoy, Victor Amadeus II, a nephew of Louis XIV, continued the anti-Waldensian policy of his uncle ; The Duke of Savoy, Victor Amadeus II, who married Louis XIV’s niece, continued Louis XIV’s religious policies : in the decree of January 1686, he banished their pastors, forbade public worship and forced parents to give their children a Roman Catholic baptism. The pastor Henri Arnaud advocated rebellion. The Waldensians were defeated in a short three-day war ; many died and 8500 were imprisoned. However, thanks to Swiss intervention, a certain number managed to flee to Geneva.

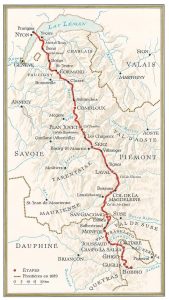

In 1688, the political situation in Europe was turned upside down when William of Orange came to the English throne and formed a coalition against Louis XIV. He sent emissaries to the exiled Waldensians in Switzerland and secretly organised their return to the Piedmont Valleys in 1689. This episode is known as the “Glorious Return“. Only 900 men managed to get back to the Piedmont ; they had to march in terrible conditions, using a very unusual route. However, they arrived in Prali, in the Val Germanica, and were able to hold their first public service on 8th September 1689, led by pastor Henri Arnaud. They swore the oath of Sibaud on 11th September 1689, loyally promising to keep together and continue their fight for the Waldensian cause, with Arnaud as their military and religious leader. They escaped from the French army as if by a miracle thanks to fog. Some days later, Victor Amadeus broke off his alliance with France and became an ally of England. The Waldensians were saved. The English put pressure on the Duke of Savoy and made him issue a decree giving the Waldensians civil rights in their territories.

The Age of Enlightenment

The Waldensian territories became a Protestant enclave in the Catholic Piedmont valleys, which became the Kingdom of Sardinia. The Austro-Hungarians now ruled over them, replacing the French.

It was thanks to the support of Churches in surrounding Protestant countries that the Waldensians were able to survive ; pastors and financial aid were sent which enabled them to set up their own schools. With the help of scholarships their young people were able to study in Geneva, Basel, Leyden or Heidelberg.

Compared to the preceding century, life was not quite so harrowing, but the Waldensians were constantly subjected to acts of humiliation and day by day fought desperately to survive at all. They lived in a kind of “ghetto”, cut off from the rest of the Italian peninsula but were attached to the rest of Europe by their links with other Protestant countries.

The Waldensians gained their freedom

The Waldensians welcomed the armies of the Revolution and later of Bonaparte. From 1795 to 1815 they were given freedom of conscience and were no longer restricted to their “ghetto”. However, all this changed in 1815 when the King of Sardinia was restored to the throne ; he brought back the former restrictive laws controlling the Waldensians. Pastor Alexis Muston was accused of publishing a thesis on the Waldensians without official permission and was taken to court. He had to flee to France, where the Protestant Church appointed him pastor in the Drôme and later in Paris. His book called The Israel of the Alps : a complete history of the Waldenses and their colonies was translated into English and German ; indeed English travelers were fascinated by it. They came to the Waldensian valleys and became benefactors of their churches. W. Stephen Gilly and Charles Beckwith, amongst others, set up an outstanding network of schools in these valleys. Charles Beckworth tried to open a school in every village and by 1848 there were 169 of them.

In 1825 Felix Neff led an evangelism campaign in the Waldensian valleys.

On 17th February 1848 Charles Albert of Sardinia gave the Waldensians legal and political freedom with the introduction of his liberalizing reforms (the “Edict of Emancipation” or “Les Lettres Patentes“). This was received with great acclaim. However, the Waldensian Church was barely tolerated and they had to struggle for over a century before receiving equal recognition with the Catholic Church. This did not prevent them from starting an energetic mission of evangelism throughout the Italian peninsula and many new communities were founded. Indeed, the building of the Temple in Turin, which was opened in 1853, symbolised their right to preach outside the Waldensian valleys. From then on, their pastors received instruction in the Waldensian Faculty of Theology, which was founded in 1855 in Torre Pelice, and later transferred to Rome. Classes took place in Italian and no longer in French. Many charitable institutions were founded, such as schools, hospitals, retirement homes and cultural centers. The publishing company Claudiana enabled the Waldensian Church to spread its influence.

During the second part of the 19th century, the Waldensian valleys faced a period of severe poverty so many people emigrated to Uruguay and Argentina, founding many Spanish-speaking churches which are still active today.

The Waldensian Church in Italy today

In Italy today the Waldensian and Methodist Churches, unified in 1975, have 25,000 members ; 10,000 live in the Waldensian valleys where they make up half the population. They have maintained strong links with the Waldensian Churches in Latin America as they attend the same synod. The Waldensian churches were founder members of the World Council of Churches, the World Alliance of Reformed Churches and the Communauté évangélique d’action apostolique (Cevaa).

In the second part of the 20th century, pastor Tulio Vinay founded two major institutions : the Agape centre in Prali in the Waldensian valleys – it is international and specialises in studying political, religious and social issues ; the Riesi centre in Sicily , a community centre which works at bringing new life to this small town.