A typical conversion

When faced with the dragoons, or hearing that they were coming, the members of the Reformed Church renounced Protestantism in droves. They converted to the Catholic, Apostolic and Roman Church, which is why they were called the “new converts” (N.C.).

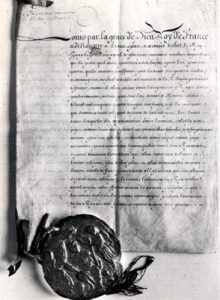

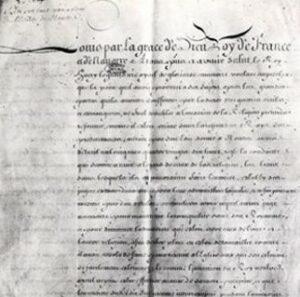

Some of them refused to recant. Despite the last provision of the Edict of Fontainebleau specifying that members of the Religion Prétendue Réformée (RPR) could “keep about their business or enjoy their possessions without being bothered”, provided they did not worship publicly, they were often persecuted and their children had to be baptised and raised in the Catholic faith.

The Catholic obligation

With the Revocation, the “new converts” (N.C.) lost their social and cultural identity and had to fulfil Catholic obligations :

- go to church,

- take Communion at Easter,

- baptise their children,

- send their children to catechism,

- receive Extreme Unction when about to die.

Catering for the new converts caused problems in Protestant areas. The existing Catholic churches had to be expanded or new ones built, which was the case in Montauban.

These new converts had to be taught catechism. The king ordered that religious books, Catholic catechisms and even copies of the New Testament which had been translated into French by Father Amelot, should be given away free. Catholic missions were conducted in Protestant areas in order to educate the new converts. Conferences were organised by Sorbonne scholars. Fénelon himself gave one in Saintonge.

In 1686, the king passed over the duty of supervising the new converts to the priests. The latter set up lists of new converts with notes about them. As a result, the priests became repressive agents of the crown. They denounced the bad Catholics, those who did not go to church, did not take communion at Easter or who did not send their children to catechism. These bad apples could have their belongings confiscated or their children taken away and placed in Catholic institutions.

The resistance of the "new converts"

The new converts tried various methods of escaping from their “Catholic obligation”. The most common way was to flee despite emigration being forbidden. This was reinforced in 1699 and again in 1713.

The second was passive resistance : refraining from going to church or sending their children to catechism as soon as the dragoons moved away. In actual fact, church attendance of the nobility was more closely supervised than that of the masses. In 1689, the priests in Anduze realised that only 10% of the new converts took communion at Easter.

Of those who had to send their children to Catholic catechism, many, once the children returned home at night, discredited Catholic teachings and taught the children to reject the Catholic faith.

According to the Edict of Fontainebleau, Catholic baptism was mandatory. The new converts submitted to this obligation in order to provide their children with a birth certificate because, from then on, only the Catholic Church was allowed to keep the registers. Conversely, the Edict did not tackle the issue of marriage. Some new converts accepted a Catholic wedding. Some others only signed a marriage contract in front of a public notary, but as a result their future children were illegitimate.

Regarding Extreme Unction, the new converts found various tricks to escape it (declaration of sudden death, no call to the doctor who had to warn the priest and the registrar about the patient’s condition).

They also actively resisted by continuing to worship within the family or with neighbour, in private gatherings. The pastors of the Refuge endeavoured to maintain these private gatherings with the printing of liturgical leaflets for “Christians without a pastor”.

Very soon, in the south, the new converts gathered in remote areas to hold Protestant services. These were called the “underground” gatherings, and were harshly repressed.