Théophile Alexandre Steinlen (1859-1923)

Steinlen was an emblematic artist of the late 19th century in Montmartre. He also drew, painted, illustrated, designed posters, and sculpted and had anarchist leanings. He preferred drawing and pastel to depicting everyday life on the street and the small trades.

Théophile Alexandre Steinlen, born in Lausanne, Switzerland, was the grandson of Christian Gottlieb Steinlen (1779-1847), a painter and drawer of German origin. Théophile was naturalized French in 1901.

He studied theology at the University in Lausanne for two years, but abandoned the idea of becoming a pastor and turned to an artistic career. He was trained for industrial ornamental design in Mulhouse. He worked in a fabric mill and designed cloth patterns. He also studied engraving, lithography and painting. In 1881 he left the Alsace region with Emilie Mey whom he married later on. They settled in Paris where he first worked as a cloth pattern designer.

A prolific artist

As early as 1883, he was located on the Butte Montmartre, and was acquainted with the bohemians and the golden youths. Adolphe Willette, a painter, introduced him to Montmartre and its cabarets. He often went to the ‘Chat Noir’ recently opened by Rodolphe Salis, where he befriended various artists such as Villiers de l’Isle-Adam or Alphonse Allais. He designed the poster for the cabaret and first exhibited his work at the Salon of independents, and after 1893 at the Salon of humorists.

In 1882 when Salis created La Gazette du Chat Noir, Steinlen delivered his first drawing in 1883 to be followed by 72 more in other issues. In 1885 Aristide Bruant, a nightclub satirist and songwriter, opened his own cabaret ‘le Mirliton’ and founded a gazette to which Steinlen largely contributed while also illustrating over 120 of Bruant’s songs. He depicted people’s lives in Montmartre, workers, trainee seamstresses and working people he watched on the streets of Paris.

From 1883 to 1920 he produced hundreds of drawings published in various magazines of the time. He realised some politically oriented ones under a nickname.

He also illustrated literary works and contributed to satirical papers such as L’Assiette au Beurre, Le Rire and les Humoristes founded with Jean-Louis Forain in 1911. He also befriended Toulouse-Lautrec.

An anarchist artist

Steinlen met some former ‘communards’ (supporters of the 1871 Paris Commune) back from exile after the 1880 amnesty law. He sympathised with socialists and anarchists, and was one of the artists the most aware of the social concerns in the late 19th century.

In 1890 he illustrated the book entitled Prison fin de siècle written by two Commmunards about the Sainte-Pélagie jail in Paris. After 1893 he contributed many drawings to the Chambard socialiste, sometimes under his nickname Petit Pierre. His work was first exhibited in 1894.

In contact with anarchist circles he denounced poverty and destitution, the hardships of the workers and the living conditions of girls on the streets. He wrote: « Tout vient du peuple, tout sort du peuple et nous ne sommes que ses porte-voix »-’ everything comes from the people, everything comes out of the people and we are mere mouthpieces’. He supplied drawings denouncing the exploitation of toiling masses, attacking the Church, the capital, the army, promoting a social Republic under the guise of a liberating and emancipating young woman.

In July 1894, after the laws on the press were passed, he and Octave Mirbeau were threatened with arrest. Steinlen went to Munich where he published in Simplicissimus, a German socialist weekly, and then to Norway.

In the meantime for the « Procès des Trente » -’Trial of the Thirty’ – twenty-five anarchists were taken to court, among them Paul Reclus and Félix Fénéon, and charged with conspiracy. When the figures in the anarchist movement were discharged, Steinlen came back to France in late 1894.

In 1895 he applied for citizenship and married his girlfriend at the town hall of the 18th arrondissement in Paris. He kept supplying drawings to various publications, such as Gil Blas, Mirliton, and also La Petite République, or L’Almanach socialiste. He was asked to illustrate conference announcements, or songs like Eugène Pottier’s L’Internationale in 1895. During the same year he designed the cover of the Soliloques du pauvre by Jehan Rictus. After 1897, he was the main illustrator for Zo d’Axa’s La Feuille (17 issues out of 25).

In 1897 he was involved in the Dreyfus case and denounced the lies of the army as well as the conspiracy of the military staff. In 1902 he was one of the illustrators for the Temps Nouveaux, along with Maximilien Luce, Félix Vallotton, Paul Signac et Camille Pissarro. He worked for the publication until 1914, and then until 1920. From 1901 to 1912, he supplied drawings to L’Assiette au Beurre denouncing injustice, social destitution and claimed his anticlericalism and his libertarian spirit. He illustrated works and brochures close to the anarchist movement, such as L’État, son rôle historique, by Pierre Kropotkine and Évolution et Révolution by Elisée Reclus.

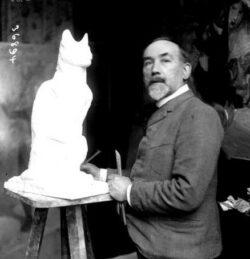

He also worked engraving such as his lithographies on the misfortunes of Serbia and Belgium in 1914-1918. He was known for designing posters, for instance the cat, which truly fascinated him, on the series of posters for the Tour of the Chat Noir, but also for his sculptures (sitting angora cat).

A committed artist

In 1902 he actively supported the creation of an Artists’union for painters and designers. He delivered his speech of accession at the Confédération générale du travail in July 1905. In 1904 he also joined the circle of designers and humorists and was appointed one of the Honorary Presidents.

In 1905, he joined the Société des Amis du Peuple Russe et des Peuples annexés chaired by Anatole France, along with Zola, Charles Andler, Séverine or Octave Mirbeau. In 1907 he attended a committee in favour of erecting a statue to honour Louise Michel. He signed various petitions, for instance in 1910 against the sentence to death of Liabeuf – a shoe maker accused of beating a law enforcement officer on duty, causing his death, or of Japanese revolutionaries in 1911.

During World War I, Steinlen toured the battlefields showing, with a humanist pacifist approach, the infantrymen and the wounded at the front but also the lives of the toiling masses in the rear.

He took part in charity campaigns, suggested the idea of a victorious, republican and revolutionary Marianne. After the war, besides personal exhibits as the 1920 one, he worked with L’Humanité, with Clarté and with Temps nouveaux. He made portraits of contemporary artists he was friends with, such as Anatole France or Maxime Gorki.

In 1923, when he died, his ashes were buried in the Saint-Vincent Parisian cemetery. Many unknown people aware of his work gathered for his funeral.

Bibliography

- Books

Associated notes

-

Félix-Édouard Vallotton (1865-1925)

-

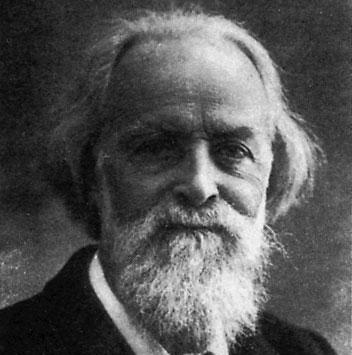

Elisée Reclus (1830-1905)

Elisée Reclus devoted all his energy to the exploration of the planet and published books which extolled its wonderful qualities. He is also known for his defense of the Anarchist...