Repression

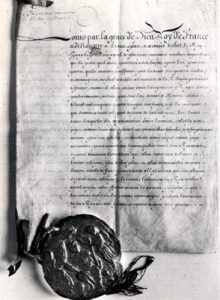

As early as 1634, pastors were forbidden to organise worship outside the town where they lived. From 1635 onwards, complaints filed against Huguenots became more and more numerous in the Clerical Assemblies’ books of grievances. In 1655, churches built outside the places specified by the Edict of Nantes (and defined by those charged with implementation of the Edict) had to be pulled down and access to religious services was restricted.

Legislation against the Alleged Reformed Religion (R.P.R.) was enforced between 1666 and 1683 and tore the Edict of Nantes to pieces. From 1661 to 1685, around 175 decrees and royal claims forbade religious worship, attendance at services, removed dignity and freedom of conscience.

Between 1679 and 1685, (even before the Edict of Revocation), about 250 churches were pulled down and the “Lord of the Manor practice” in castles and chapels was gradually prohibited. Then, people spontaneously gathered on the very sites of the former churches.

The first meetings

As early as 1682, the practice of secret meetings began in the southern Provinces (in Drôme,

near Anduze and in Vauvert, then in Cevennes and Languedoc), on the sites of demolished churches.

In 1683, 32 members of the Reformed Church were arrested in Drôme and Château-Double, while 300 others set up the “camp of the Eternal” and clashed with four regiments of dragoons.

The battle ended in Bourdeaux (Drôme), with the arrest of 50 rebels who were burned at the stake or hanged. The lawyer, Claude Brousson (1647-1697), tried to encourage spread of this movement throughout France to show the king that, although the churches had been destroyed, the Protestant communities were alive and well. The whole thing turned into a riot, which was harshly repressed.

After the Revocation

In July 1686, a declaration made provision for using the death penalty against those “caught organising meetings” with life in the galleys for males that helped them, and a prison sentence for females.

In areas where Protestants were few, they gathered in each others’ homes. In Holland and in Switzerland, some pastors tried to make these meetings easier by printing a “liturgy for Christians without a pastor”.

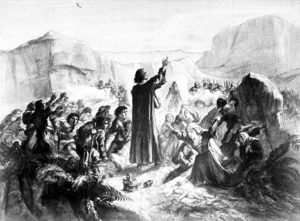

In regions where Protestants were numerous, resistance was public. First, great numbers refrained from going to Mass once the dragoons left. Most importantly, they called secret meetings in remote areas, mostly at night, to hear sermons and occasionally celebrate the Lord’s Supper. Unlike the very first meetings, these were no longer presided over by pastors as they had had to flee or recant. So meetings were organised and led by lay people : the preachers.

The preachers

Particularly in the Southern Provinces, many tens of preachers had an itinerant life, hunted down by soldiers (1686 declaration). Most of the preachers were young and not very well trained. The best known was the lawyer, Claude Brousson, who came back to France in 1689 after he had been a refugee in Switzerland since 1683. He began presiding at secret meetings in Cevennes and Lower Languedoc and later in the Northern Provinces. His sermons, written in the “Desert”, were copied and distributed to people. Some were published in Amsterdam.

Some pastors who had moved abroad answered the call of their “shepherd” and came back to France, putting their lives in jeopardy. Five were arrested in Paris and sentenced to life imprisonment on the island of Sainte Marguerite, off Cannes. Others led an adventurous existence as preachers. Among the most famous preachers we must mention, besides Claude Brousson, tortured in 1698, Fulcran Rey hanged in 1686 and Francois Vivent executed in 1692.

In Cévennes and Lower-Languedoc

On April 26, 1686, a meeting in Saint-Germain-de- Calberte was caught unawares by royal troops. In Lasalle, Gard, secret meetings were held as early as 1686, notably in the caves at Pagès. Despite ruthless repression by Intendant Basville, the secret meetings multiplied. Cevennes and Lower Languedoc had the largest number of preachers : about sixty between 1685 and 1700. However, by 1700, nearly all the preachers were dead or in exile.

Some meetings were protected by armed security guards who did not hesitate to shoot at the king’s soldiers. Some preachers contacted the Protestant princes who had allied their forces against Louis XIV during the War of the League of Augsburg. A plan to land allied troops on the Languedoc coast, in conjunction with an uprising in Cevennes, was aimed at restoring the Edict of Nantes in France. This landing never took place, but the royal authorities increased their surveillance of secret meetings and toughened punishments.

In Upper Languedoc, the Tarn mountains and the Lacaune hills, numerous meetings were held after 1685. The most notorious was the one in Saint-Jean-Del-Frech in 1689, which led to the massacre of 50 people. Among them was the preacher, Corbière de le Sicarié, killed in Pierre-Plantée, near Castelnau-de-Brassac. Every year a Protestant ceremony is held in this place of memorial on the last Sunday in August.

In Dauphiné and Ardèche

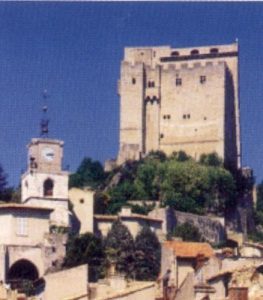

In 1686, secret meetings were called in Calençon and Plan de Baix, Ardèche. Between 6 and 6000 attended these meetings. Those arrested were jailed in the Crest Tower (Drôme), sentenced to the galleys or hanged.

From February 1688, a strange movement started in Drôme : prophetism.

Near Crest, a young shepherdess, Isabeau Vincent, started preaching in patois, and then in French, while asleep. She attracted a crowd of followers who collected her prophecies and sent them to the Refuge where they were printed as small volumes which were then distributed all over France. The young prophetess, and several young girls and boys, started prophesying all over the area. In January 1689, the movement of the “little prophets” crossed the Rhône and stirred up the people of Vivarais. The prophetic gatherings multiplied. Since they were convinced the Holy Spirit would protect them, people did no longer took heed of any danger. On February 19th, 1689, near Saint-Sauveur-de-Montagut (Ardèche), the audience refused to run away as they were convinced the angels would protect them from any shots : 400 people were killed. The prophetic movement was not seen at large meetings any more, but remained hidden in small hamlets and private homes until it reappeared in 1700 in Cevennes and Lower Languedoc.

In the rest of France

In Poitou, in 1688, a meeting was held in Grand Ry near Mougon (Deux-Sèvres). The dragoons found 1500 people at prayer and shot at them like pigeons.

On the Arvert peninsula (Charente-Maritime), secret meetings were held in the dunes or the forests but persecution was not as violent as in the south.

Around Sedan, the Huguenots were decimated by the arrival of 300 cavalry and 17 companies of the Champagne regiment in November 1685. Those who escaped the massacre worshipped in the woods but were also sentenced to prison or the galleys.

In Béarn, meetings were organised in private homes and in the woods around Pau. In 1698, after presiding over two meetings in Pau, Claude Brousson was arrested in Oléron and then tortured to death in Montpellier.

In the Dordogne Valley, the Reformed Church congregation gathered to sing psalms in the ruins of the church at Bergerac, destroyed in 1682. In 1688, a woman, “la Montjoie”, was hanged for holding secret meetings.

In Normandy, the Church of the Desert was supported by Claude Brousson. Large meetings were cancelled and replaced by preaching in private homes. Around fifteen meetings were surprised around Condé-sur-Noireau, Bolbec and, Crocy and, as a result, 300 people were sentenced to prison, 37 to the galleys and 18 to death by torture.