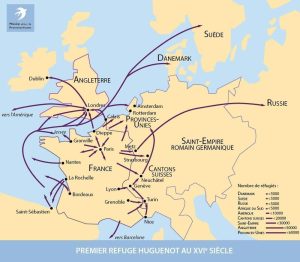

The First Refuge

The first wave of departures, called the First Refuge, took place as early as the 16th century. Following the first persecutions in 1560, and especially after the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, fugitives left the kingdom for Geneva, England or the United Provinces. In the latter they met other refugees, French speaking Flemish who had founded the first Walloon churches. A French diaspora settled there.

Calvin encouraged departures for the sake of religious virtue [«que ceux qui croient de n’avoir pas la force de témoigner de leur foi s’exilent» (let those who believe they do not have the strength to testify to their faith go into exile)]. Theodore de Bèze alluded to «l’universelle proximité du ciel nul n’ayant de cité permanente» (the universal proximity of the heavens as no one has a permanent city).

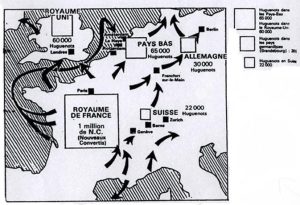

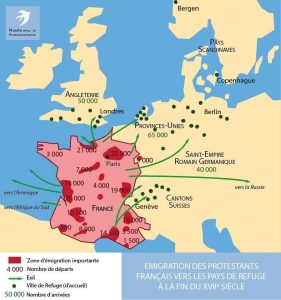

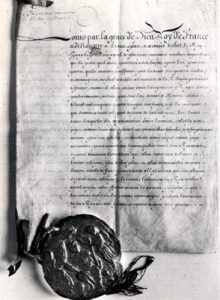

The Great Refuge

After the Edict of Nantes (1598) departures decreased considerably, and some emigrants even came back to France. But each crisis (+the taking of La Rochelle in 1628, the dragoon attacks in Poitou in 1681), led to new departures even though a royal edict (in 1669, renewed in 1682 and 1685, extended to “new converts” in 1686 and 1699) forbade them to “settle in foreign countries”. The number of exiles reached its peak with the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, decreased during the war of the League of Augsburg (1688-1697), and increased again after the Camisard War (1702-1704). Some even left once Louis XIV had died in 1715, as the Regency did not alter the legislation and did not stop repression. To the first three countries of the First Refuge were added Germany, especially the Electorate of Brandenburg (Prussia to be) and that of Hesse-Kassel, which attracted the surfeit of refugees going through Holland, but more importantly through Switzerland and Geneva. Departures to Scandinavian countries and even to Russia were mentioned. There were often stories involving the Cape of Good Hope and New World English colonies.

The second wave was called the Great Refuge: from 1680 to 1715, 180,000 French left their country, the largest migration movement in modern French history.

The exit channels

Over 100,000 people crossed borders between 1685 and 1987.

A soon as Louis XIV forbade the Reformed to emigrate in 1669, and again after the revocation of the edict, men who were caught were sent to the galleys and women to jail. The exit channels were closely watched.

The sea was easily crossed from the ports of Bordeaux, La Rochelle, Dieppe and Rouen, where rowing boats came and fetched fugitives and took them to English, Dutch or Danish ships anchored offshore. The ships left with a few official passengers, such as pastors, but mostly with clandestine travellers, in terrible conditions down in the holds after they had paid the smugglers handsomely. The attempts often failed because of informers.

Normandy, through Dieppe and Rouen, had the highest number of emigrants with English ports and the Channel Islands being close.

From the South people sometimes went to Bordeaux, and then to England or to the New World. But most of them embarked in Marseilles or Nice for Genoa, and then went on land to Turin and finally to Geneva.

Huguenots from the Dauphiné, Vivarais, Cennes, Languedoc, Provence regions, as well as from French cities in the Piedmont mostly went by land. They went to French-speaking Swiss cantons, the Republic of Geneva, the Principality of Neuchâtel. Protestants from Burgundy, Champagne, Lorraine went towards Rhineland countries. Journeys came up against natural obstacles, principally the river Rhone with its very few bridges. The Jura region on the way to Lausanne was difficult to cross as Montbéliard was French, and there were few bridges in the Doubs gorges. Surveillance was intense, but “with money you can cross the Rhone anywhere” a boatman testified.

In Lyon, an important passage point, it was easy to blend in the big city, to recruit a more or less dependable smuggler, and to wait for an opportunity. Some foreign traders even came to the fairs to take charge of the fugitives and take them to Lyon. They walked by night, hid during day and were dressed as beggars, peddlers or rosary vendors. They pretended to be sick, mute, or mad. Deaths from exhaustion, hunger or cold were not uncommon. It was a risky business, arrests were frequent and emigrants sent to the galleys, while smugglers could be hanged. Handwritten manuals gave the itineraries and crossing places, sometimes the names of people one could ask for help.

The Northern Border had many hidden traps because of the complex and changing geography of places occupied by French or Dutch garrisons. Those who were caught had to recant to be freed. Travelling on their own or in small groups with relatives, friends or neighbours, men often going ahead to make ready, women and children coming later.

Refugees, especially those of the “second generation”, often found a cousin or a neighbour in European cities. On arriving in a foreign country the Huguenots were bound to go to church and attend the preaching of the word. Most of them, obliged to recant in France, had to be “reconciled” at the end of a public ceremony and to “acknowledge” their transgression.

Hospitality in the Refuge countries

The shared religion meant hospitality was forthcoming. Everywhere there were great efforts to assist and outpourings of compassion.

Especially in Switzerland, various administrative structures were set up to deal with the immediate needs of the refugees whose material condition was often close to misery – lodging, transport, direct financial help. To collect money, parishes organised lotteries and days of prayer. But the burden was sometimes considered too heavy, and refugees were then asked, or forced, to find shelter elsewhere: Switzerland and Holland, for instance, were transit places and encouraged the refugees to go to Germanic countries, where they were better received.

But social tensions appeared, and contrary to the protestant history of charity, the Refuge was not always a positive affair. Once the first emotion had waned, the burden of emigration became heavier and heavier. Public opinion was not always understanding: fear of competition for merchants and craftsmen, jealousy of tax exemptions for the refugees or even cultural opposition, the Northern Protestants not always appreciating the effusive Southerners.

Number of refugees and hospitable countries

It is difficult to assess the number of refugees at the end of the 17th century. Fancifully, some estimates suggest up to 2 million. Voltaire reckoned there were 800,000. The Huguenots tended to overestimate, and the Catholics to reduce it by 50,000 or so to decrease the importance of the drain on the country’s productivity. A number between 160,000 and 200,000 is currently accepted and represents 25% of the 800,000 estimated protestant population. The special status of pastors was remembered. They had to choose between conversion and exile, the latter being forbidden to their followers: 80% of pastors went into exile.

Depending on the host countries, the following numbers are likely:

- Switzerland and Geneva: 60,000 reformed, particularly those from the South, went through Switzerland where they received generous help. The main crossing place was Geneva, where supposedly only 20,000 settled.

- The United Provinces: the first refuge country because of its easy access, of its secular tradition of liberty, and of hospitality in the Walloon churches. 70,000 were received, but it is difficult to know how many settled, as Amsterdam and Frankfurt were hubs for the Refuge.

- England: 40,000 to 50,000 Huguenots were received, originating from maritime provinces. The churches founded at the time of the first refuge in the 16th century, persecuted under Mary Tudor, had regained their rights under Elizabeth.

- Germany: about 40,000 Huguenots definitely settled there, mainly in Calvinist principalities: 20,000 in Brandenburg, where the Great Elector published the Potsdam Edict in 1685, making it particularly attractive; in the Hesse-Kassel region, where the landgrave issued an edict on hospitality and privileges in April 1685; the Palatinate, and the county of Lippe. Later on, under pressure from the refugees, some Lutheran states and cities agreed to receive them:, Bayreuth, Hesse, Darmstadt, Stuttgart, Nuremberg.

Other Huguenots, a small minority settled further away in Protestants States of Northern Europe, and overseas in South Africa or in British colonies in North America.

Returns were very few because Louis XIV was wary of the newly converted likely to cause trouble in France at war. The confiscated properties were added to the Domain, their incomes used to develop Catholicism i.e. schools, churches, hospitals. But the results were disappointing because properties were either sold before the people left, or they were fictitious sales to relatives or trusted friends, who were supposed to forward the revenues to the immigrants. Lawsuits were innumerable, management an administrative conundrum, and the overall profits from the dispossessions were insignificant.

The consequences for host countries

The refuge was a momentous event in European history that transformed Europe at the end of the 17th century and all through the 18th century.

It played a key role in the “European crisis of conscience” during the years before Enlightenment. From a religious point of view, the Refuge helped balance Lutheranism and Calvinism.

The benefits of the Refuge for the economies of host countries are a permanent feature of the Protestant historiography. Demographic growth helped make up for the losses suffered in the Thirty-Year War (1618-1648). The less developed States of Germany gained from the inflow of capital and of know-how from people coming from far more developed countries.

The arrival of qualified craftsmen boosted activity in many sectors, such as textile or clock-making in Switzerland. Commercial exchanges grew as the affluence of the Amsterdam middle-class testifies. But the burden of immigration and the management of refugees steadily became heavier. The competition with the new craftsmen was deemed dangerous, and public opinions did not accept the opportunities granted to the refugees. It is difficult to quantify the economic contribution.

On the other hand, the cultural contribution was unquestionable. The French Huguenots took an active part in the conciliation between the host country and their homeland. The intellectual elite who chose exile, tried to keep in touch with their original culture. Helped by the diaspora, channels of exchange and influence were established. In Holland, as well as in Switzerland and in England, publishing was booming thus promoting and spreading French as a language of culture. The Huguenots contributed to turning French into the most spoken language in Europe among intellectuals. Magazines, political and literary gazettes were written in French. A number of booksellers were refugees, former self-employed professionals or teachers. All these elements created a sort of learned cosmopolitanism, the “Republic of Letters”. The Huguenots took part in the opposition to Louis XIV and the principle of absolutism.

Such interactions were usually forbidden. Books and gazettes were circulated in secret, smuggling networks were set-up allowing the delivery of prohibited books to the Protestants still in France: critical editions of the Old and New Testaments, catechism, sermons, historical studies. Those books, mostly meant for Protestants in the South of France, were printed in Switzerland, in Geneva and Lausanne.

On the whole, it can be said that the Refuge emphasised the opposition between Catholic Southern Europe and Protestant Northern Europe.

Assimilation

For a long time many refugees from 1685 hoped that Louis XIV would restore the Edict of Nantes. The Peace of Ryswick that put an end to the War of the League of Augsburg (1688-1699) was the first disappointment; negotiations were underway, but Louis XIV flatly refused the mere idea of return unless people converted, which was seldom the case. “Protestant powers had rather to negotiate territorial advantages than defend their co-religionists.”

Exile was for good. The weakest and poorest were uprooted, marginalised, and went from Church to Church until they died. Other refugees were gradually assimilated, married natives. The French language was piously kept within families, but it evolved and drifted away from the classical pattern, Voltaire named it the “refugee style”; it was either anglicized or germanised. It remains in use in some parishes, and the Huguenot history societies promote the “return to the roots”.

At the time of the Revolution, Huguenot refugees were offered the possibility to return to France by the Royal Edict of 15 December, 1790, to be made French citizens again, and to recover their property. A very restricted number took advantage of this edict, the most famous one being Benjamin Constant. The law remained in force until the end of World War II.

Conclusion

The Revocation (of the Edict of Nantes) marked a definite break in the history of Europe. As the Sun-King was at the peak of his political might, France lost a large part of the power behind its economic and cultural influence, which Michelet called “the French elite”. All the refugees gave new impulse to every area of life in the countries which took them in, marking the collective