Times of Peace

The peace of Saint-Germain seemed possible in spite of the difficulties between the Protestants and Catholics to live together, with notable sporadic problems as early as November 1570 in Amiens, Rouen and Orange.

Catherine de Medici tried to strengthen her alliances abroad. Since the interview in Bayonne, the relations with Spain had deteriorated. Gaspard de Coligny, who had returned to favour at the Court, recovered his rank of Admiral and participated in the private council, he pleaded for a French intervention. Fighting against Spain, a common enemy, was the best way to get Catholics and Protestants together again. But the project was not pursued, the prestige of the powerful Spanish army was enhanced by its victory over the Turks at the Lépante battle on 7 October 1571.

To reinforce the home situation, Catherine de Medici, who strongly believed in marriages between royal families, decided that her youngest daughter Marguerite would marry the Protestant Henri de Navarre – King Henri IV to be. Her mother Jeanne d’Albret first refused, but was later convinced. On 11 April 1572 the marriage contract was signed by Cardinal of Bourbon, uncle of the king and future member of the league.

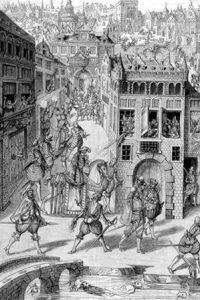

Henri de Navarre entered Paris on 8 July 1572 surrounded by 900 Protestant noble men in black, the king being in mourning after his mother’s death one month before. The wedding took place on 18 August at Notre-Dame: a huge stage was set up outside, Henri led his spouse to the choir of the cathedral so that she could listen to the nuptial Mass celebrated inside, but he walked out and did not attend Mass, the nuptial benediction was then given on the stage. Sumptuous feasts took place for three days, and were meant to establish the reconciliation between the two parties.

Times of War

The news of the king’s sister marrying a Protestant astounded the Parisians who were strongly attached to traditional Catholicism. To their eyes the Huguenot was a foreigner responsible for a decade of woe in the country. They idolised Henri de Guise and were outraged at the protection the Court seemed to give to the defeated heretics. In Paris Calvinists were a minority and worshipping was forbidden even in peaceful times. Most of them lived on the left bank, thus the Saint-Germain district was called “little Geneva”.

Admiral Gaspard de Coligny settled down on the rue de Béthisy near the Louvre, and was guarded night and day by Swiss Guards. He knew his life was threatened and never went out without his supporters. On Friday 22nd of August as he was walking to the King’s Council and reading a letter, a shot was heard that injured his right hand and his left arm. The news spreads all over the city and the worst was expected.

The Protestants gathered around the Admiral’s house and requested an inquiry, as they deemed the Queen Mother and the Duke of Anjou responsible. The king decided on an investigation. But it might reveal the people responsible for the assault, so the King’s Council persuaded him that the chiefs of the Huguenots had to die because they wanted to take power. Charles IX gave in and the list of victims was drawn up.

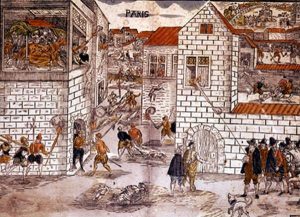

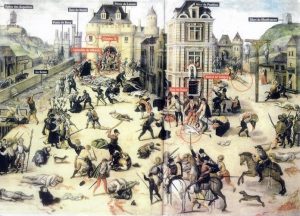

Order was given to close the city’s gates, to chain up boats on the Seine to prevent any escape. When the bells tolled, the execution started at dawn on the 24th of August under the Duke of Anjou’s surveillance. Gaspard de Coligny was assassinated at home, thrown out of a window in the street, emasculated, and beheaded. Children dragged his body in the streets, which was then hanged on the Montfaucon gallows, used for ordinary executions. The killers scattered in the courtyard of the Louvre, in the rooms and the galleries.

All the Huguenots nobles were killed, except for the blood-princes Henri de Navarre and Henri de Condé, provided that they recanted. The de Guise troops spread all over the Saint-Germain -l’Auxerrois area where all the Protestants were killed. Only those living in the Saint-Germain-des-Prés area managed to escape. Two hundred nobles were killed and their bodies gathered in the courtyard of the Louvre.

The following day militiamen took up arms and killings spread all over the city. It lasted for three days, and the city doors stayed closed. In order to identify one another the slaughterers hung a white crosses on their clothes and hats. The cutthroats killed randomly after denunciations, not sparing women, children, or even some middle class Catholics. Monks incited the killers to rid Paris of the “damned race”. Blood ran in the streets. Over 1,800 corpses were pulled out of the Seine river.

On the 25th of August 1572 Charles IX ordered the provost of merchants to stop the killings and protect the survivors. The following day the King went to Parliament and assumed the responsibility for the killing of the Huguenot chiefs. He alluded to a plot by Gaspard de Coligny against him and his family. The culprits having been chastised, the King claimed he did not wish to harm the other Protestants who remained under his protection.

The number of 4,000 dead was generally acknowledged. As early as August 24th, the news of the Parisian massacres reached the provinces. All cities would be concerned: 1,200 victims in Orléans, 600 in Meaux, 300 in Roanne, between 500 and 3,000 in Lyon, etc. Messages from Parisian extremists, but not from the King, incited these massacres without precise instructions. The attitude of the local authorities varied. Some drove to killing, others let it happen like the mayor of Bordeaux where about 3,000 people were killed.

But the horror of violence, as well as the looting, sometimes caused magistrates and members of the clergy to try and protect the Protestants, often by jailing them. On August 31 in Lyon however the people had the doors of the Cordeliers prison opened and killed all the prisoners. Certain governors tried to limit the massacre: “I always served the King as a soldier, and would be sorry to act now as an executioner.” one of them said. Massacres went on for several months: “Saint Bartholomew was not a day but a season” Michelet wrote. Assessing the number of deaths was difficult – between 7,000 and 21,000.

To justify the event, ambassadors were sent to European Courts. Pope Gregory XIII celebrated the event with a mass of thanksgiving and had a medal stamped. Philip II had a Te Deum sung, Emperor Maximilian II, Charles IX’s father in law, denounced the murder of Gaspard de Coligny as a tyrannical act. In England, in Switzerland and in the Netherlands, outrage was felt. A number of terrorised Protestants recanted. Many went into exile to the “Refuge” countries, such as Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands and England.

The Southern regions, Languedoc and Vivarais, Cévennes and Montauban reacted and took up arms, and the cities were forbidden to royal troops. Sommières was besieged by Count Damville-Montmorency for two months. The city was defended by Cevennes inhabitants who carried a tin spoon in their hats like Zeland -a province in the Netherlands known as “gueux”. Damville spared their lives. The siege of Sancerre from March to August 1573 was terrible and the population famished. The defenders’ lives were spared.

But La Rochelle gave the most outstanding example of resistance. Refugees from all over the kingdom came there. Pastors preached fighting, invoking the Bible, several of them were part of the city council. The siege led by Henri d’Anjou lasted from March to August 1573. Several assaults failed. The failure of the English rescue expedition did not discourage the population supported by the passionate sermons of it’s pastors. But food progressively became scarce, and the population was exhausted. On the 11th of May, La Rochelle was saved when Henri d’Anjou was elected to the throne in Poland. He abandoned the siege and signed an armistice on the 21st of June 1573.

The edict of Boulogne, registered by the Parliament in Paris on the 11th of August, pronounced peace and putting behind the Saint Bartholomew horrors. It granted freedom of conscience, but freedom of worship was limited to three cities, namely La Rochelle, Nîmes and Montauban, and later Sancerre. It was the most restrictive edict as the Holy Communion was forbidden even at lords and Chief-justices homes.

The exceptionally violent aspect of the Saint Bartholomew Massacre made historians ask many questions. Whether it was to defend the royalty against a plot, or a universal conspiracy of Catholic monarchies against the Protestants, or a vendetta of the Guise clan, or a bargaining chip for peace with Spain who demanded that heresy be destroyed, or a “crime against a social class” the poor against the rich Huguenots, the Saint Bartholomew Massacre still seems one of the great mysteries in the wars of Religion (Le Roux).