The Church of the Augsburg Confession began to develop

Theological debates began to develop. Melanchton (1497-1560), a friend and pupil of Luther, steered a middle course : he insisted that justification by works was less important than the promise of grace given to all men, who were justified by faith ; loyalty to God was essential ; everyone had to work where he had been placed in the world, according to the calling entrusted to him by God. This was the main thing and it is what he affirmed at the Diet of Augsburg (organized by Charles V in 1530) ; this declaration had been drawn up with Luther’s participation and it was signed by seven princes and two free towns ; it led to the establishing of the churches called the Churches of the Augsburg Confession(les Eglises de la Confession d’Augsbourg) and in 1555 it became the confession of faith of the Lutheran Church.

However, theological discussions continued, due to the fact that Melanchton was moving towards a more spiritual conception of the real presence of Christ at the Last Supper ; this was close to the Calvinist point of view. The Concord Formula (1557) aimed at bringing to an end these disputes and established the Lutheran orthodox statement of faith which would be adhered to by two thirds of the German protestants at a later stage.

Nevertheless, Calvinism had a certain influence, supported by Zurich and Geneva – it originated in the university of Wittenberg. First of all, the Palatinate took up the reformed faith, which had been expressed in the Heidelberg catechism (1563). This is because Frederic III, after hesitating for several years, was converted. Later on he was joined by the duchy of the Deux-Ponts, the town of Bremen, many small northern principalities and especially the Elector of Brandenburg : in 1613 Jean Sigismond chose Calvinism, but strangely enough he did not force his subjects to follow suit so they remained Lutheran : as protestants had to give each other mutual support, the other Lutheran princes omitted to criticize him in public. This support also found its expression in the warm welcome given to protestant refugees, especially in the Brandenburg district, where there were many French Huguenots.

At the end of the XVIth century and the beginning of the XVIIth century, theological disputes continued to hold sway between Catholics and Protestants ; it was called the period of “denominations”, when each religion developed its own structure ; the jubilee of the Reformation movement in 1617 did not succeed in bringing them together. What’s more, in 1618, the terrible devastation of the Thirty Years War (1618-1648), began to take effect ; this was in effect a religious war between Catholics and Protestants. Afterwards, the political situation became clearer and a certain balance was achieved between the two religions.

The Lutheran Reformation movement

The most important period in German XVIth century history was focused on the Lutheran reformation movement ; indeed, it was a turning point for theology, religion, language and politics.

After the Diet d’Augsburg (1530), which failed to conciliate Lutherans and Catholics, it was the Lutherans who were the most numerous in most of northern, central and eastern Germany. On the other hand, the Lutherans were in the minority in the Rhineland and in southern Germany, with the exception of Wurtemberg ; their Churches were scattered, either in small princedoms controlled by the prince, or in towns where they were controlled by the magistrate. The Empire was a very complex legal and political structure ; in some parts of it, in Germany and Hungary, where the emperor’s authority was not very strong, free towns and principalities were able to govern themselves.

When the attempts at reconciliation between Lutheran and Catholic theologians failed (the colloquies of Haguenau, Worms and Ratisbonne) due to the key subject of justification ; Charles V, after having made peace with François 1st (1544), returned to Germany, determined to convert its inhabitants to Catholicism. However, he had not reckoned with the protestant princes or the free towns who set up the League of Smalkade : the elector of Saxony and the landgrave (count) of Hesse were the two main leaders of this anti-imperialist party. Although the protestant princes did not win the war called the League of Smalkade (1546-1555) in Muhlberg , Saxony, with the help of France (treaty of Chambord), they were able to keep the Emperor at bay. The war ended in 1555 with the treaty of Augsbourg. Both the Catholic and Lutheran faiths were officially recognized and religious unity was imposed in every territory : each prince had the right to choose between Catholicism and Lutheranism and to impose his choice on the inhabitants of his principality. This was called the principle of “cujus regio, ejus religio”, whereby one religion was taken up by a political unit (principality or free town), whose protestant leaders (king, prince, council) were even made responsible for the appointment of pastors ; kings and princes were often “summus episcopus” – head of the church in their principality or kingdom. Their subjects had only one choice, either to submit or to emigrate with their possessions. In this way, Lutheran Churches were linked to political power and the prince’s duty was to watch over the spiritual and temporal salvation of all his subjects.

The peasants' revolt

Nevertheless, the political situation remained confused. When Luther criticized the spiritual authority of the Catholic Church, the princes seized this heaven-sent opportunity to take advantage of the situation for their own personal gain : they seized control of the churches, restricted the activities of the clergy and confiscated their goods. What’s more, the publication of Luther’s theses, calling for greater social justice, were interpreted by certain members of the population to mean that a radical revolution of society was in order. Extremists and prophets came forward. Thomas Munster denounced temporal knowledge, insisting that God had revealed his will directly to his elect ; he called for the extermination of the wicked, whom he gradually came to associate with those in power.

In 1525, the “peasants’ revolt” spread throughout southern Germany and even into some parts of Austria, destroying in its wake anything which the rebels considered to be symbols of power (churches, convents, castles). The reprisals were terrible : Munster was tortured to death. The Anabaptists, who were attracting followers in Switzerland, had the same radical approach ; their influence spread to the Rhineland and the Low Countries, where they were brutally suppressed in 1585. Luther was alarmed at the violent consequences of his social criticism and the destruction wreaked on the country by the iconoclasts. In order to re-establish authority, he understood that it was essential to bring back moral discipline, doctrinal purity and new official churches. He was joined in this opinion by Calvin (“the fear of God is the beginning of religion”), Zwingli and Bucer. He also thought it was very important to have the support of the non-religious authorities.

In the XVIIth and XVIIIth centuries pietism developed

Pietists emphasized the importance of emotional reactions in religion and also inner spirituality, prayer and individual sanctification ; leading members of this movement were P.J. Spener (1635-1755), A.H. Francke (1653-1727), Count Zinzendorf (1700-1760) and his Moravian Brothers community. Great progress was made in the teaching of technology, ahead of its time. The university of Halle was of great renown.

The XIXth century

The most important event at the beginning of the century was the series of Napoleonic invasions which resulted in the downfall of the Holy Roman German Empire in 1806. In its place, the Confederation of the Rhine was set up, grouping together the principalities according to different criteria ; this changed the political scene considerably, except in Prussia. When the French had to admit defeat at the treaty of Vienna (1814), the Austro-Hungarian Empire, predominantly Catholic, began to increase in stature and emerging as another strong economic and political power, that of Prussia, which was predominantly protestant.

According to Luther’s Episcopal organization, the heads of state, who also had full responsibility for the Churches, were obliged to gather together all the protestants, even if they had to resort to force to do so. These meetings of unification were held in Prussia and Nassau in 1817, in Hesse in 1823, and in Anhalt in 1827.

In Prussia, although the Hohenzollern were Calvinist, their subjects were mostly Lutheran. For a long period, this did not cause any major difficulty between the Prussian Lutheran Churches and the State ; however, little by little the idea caught on of an administrative reform which would bring together the State and both protestant faiths. When the theologian Schleiermacher was consulted, he suggested setting up a communal administrative structure called the united evangelical Church, to allow the Churches more freedom in their choice of ministers and to establish Presbyterian councils and synods. Unfortunately this project never came about because the King of Prussia wanted to remain the “summus episcopus” of the Church – indeed it was only at the time of the Republic of Weimar that the situation changed.

When lord Bismarck (whose religious instructor as a child had been Schleiermacher), became the Chancellor of Prussia and later of the German Empire (1871-1890), his main desire was to avoid friction with the Catholic Church. Above all, he tried to reorganize the Protestant Church along more modern lines ; to this end he set up provincial synods, attended by elected laymen. As part of his policy of “Kulturkampf” (the fight for culture) and also according to the Lutheran doctrine of the two kingdoms, he managed to establish a clear-cut distinction between spiritual and worldly authority, although the links between Church and State were maintained. The latter was especially involved in social politics and had a certain amount of control over the Churches, for example, the principle was laid down that private religious teaching was no longer allowed, nevertheless, the State undertook to establish some form of religious instruction in every school.

In the XXth century

In 1925, the Christian National Movement (Deutschen Christen) came into being, which insisted on “positive Christianity” – this became the Nazi ideal of German Protestantism. In 1927, in Königsberg, the “German evangelical Kirchentag” declared the “close union between Christianity and Germanism over thousands of years” ; in opposition to this declaration the “Christian Socialists” maintained that Christianity and fascism were irreconcilable.

On 30th January 1933, Hitler came to power. Catholicism was soon silenced due to the concordat (20th July 1933) signed with the Vatican, represented by Cardinal Pacelli, the future Pius XII. In March the “Deutschen Christen” obtained 43.9 per cent of the votes at the ecclesiastical elections. In May the bonfires of “anti-German” books started and in the new elections of July which were organized by Hitler himself, the “Deutschen Christen” obtained 3/4 of the votes ; the slogan “one people, one empire, one leader” was part of the new statement of faith. In the churches, a sword was placed on the altar instead of the cross and “Mein Kampf” instead of the Bible.

However, resistance soon got under way. In April 1933, Dietrich Bonhoeffer and later Martin Niemöller openly showed their disapproval of anti-semitic ideology. In November, there was a gigantic demonstration in the Palace of Sports, where members of the national Church read out its new constitution in public : this consisted mainly of racist and anti-semitic policies. Shortly afterwards, a proclamation was read out- in all anti-nazi communities (1/10th of the German parishes) publicly denouncing the principles and activities of the “Deutschen Christen”.

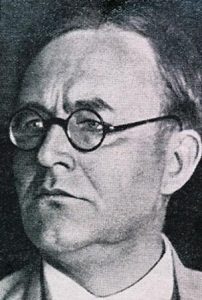

At the end of May 1934, in Barmen, the first non-official Synod of the ant-Nazi Church was held (the “Bekennende Kirche” : formed from communities and unions of the Lutheran and reformed Churches). At this synod it was decided that something must be done to actively oppose National Socialism and its attempts at taking full control of the Church. Karl Barth, together with the Lutheran Hans Asmusse, was one of the main contributors to the final text of the “Theological declaration of Barmen” on 31st May 1934. This was a “biblical Christian testimony according to the tradition of the Reformation movement.” However, in fact, only religious matters were dealt with – it was an act of spiritual resistance in defense of the Church and the purity of its message but was not a political act and in particular, no mention was made of the Jews. Only Barth and Bonhoeffer were aware of the importance of this consideration, which was gradually taken into account over the following years. Although several aspects were overlooked, the “Declaration of Barmen” did contribute to the setting-up of a resistance movement among German protestants.

After the Second World War, Germany was divided into two states : the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) consisted of the territories which had been occupied by America, England and France, while the German Democratic Republic (GDR) consisted of the territory which had formerly belonged to Russia.

The German Evangelical Church (Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland) (EKD) was founded in 1948 in Eisenach : it gathered together German Lutheran, reformed and united Churches.

The fundamental Law of the Federal Republic in 1949 institutionalised the Catholic and Protestant Churches and recognized them as corporations governed by public law ; they had to pay taxes and give religious instruction in the schools – attendance was compulsory for all those who professed to belong to a religion. The protestant Diakonische Werk (Social action), set up in 1957 organized many large-scale structures in social and medical fields, financed by the Church tax. The reformed Johanniter-Order is very active in the world of emergency medical aid and care for the elderly. The Church also finances the “evangelical Academies” where courses are held on social problems.

Sadly, the united Church movements of the EKD came to an end in 1969 because of the cold war and the communication difficulties due to the iron curtain (the Berlin wall was built in 1961).

Between 1969 and 1990, the eight Churches of the GDR participated in the Evangelical Federation of the Churches of the GDR.

During the communist period, numbers declined considerably in the protestant Churches. The Lutheran, protestant and united protestant Churches, who had the most followers in the GDR, were in a very difficult situation : they had to deal with the controlling power. The police (the STASI) recruited members of the protestant Churches. Nevertheless, it is in these Churches, particularly in Leipzig, Dresden and East Berlin that aspirations for freedom came into being and were carefully nurtured ; this resulted in the fall of the Berlin wall in November 1989 and the reunification of Germany in 1990. The eight regional Churches that had previously been in the GDR, joined the EKD in 1990.

Today, the EKD consists of 23 regional Churches situated throughout Germany : 10 are Lutheran, 2 reformed and 11 belong to the united Church. Within these united regional Churches, local communities have the choice between :

- Following the Lutheran tradition with the Confession of Augsburg and Luther’s catechism,

- Following the reformed tradition with the Heidelberg catechism,

- Or, for united communities, it is possible to choose between one or the other or even opt for both together.

A pastor can only serve in a local Church if he respects the tradition which has been chosen by that particular Church.

Since the reunification of Germany, Protestants are slightly in the majority : there are 29 million Protestants for 27 million Catholics ; (the protestants are in the majority in the former GDR). The EKD encourages its member Churches to become a united body. Apart from the EKD there are also free Churches – Baptists, Methodists and Pentecostal communities, who number about 3 million.

Pastors can choose to follow either religious confession of faith or both in their ministry, but they are obliged to respect the Declaration of Barmen.