A pacifist group

In the early 20th century, the main characteristic of Protestant intellectuals was their commitment to moderate or radical pacifism. They were opposed to war with the German people with whom they shared the same Protestant faith. The commandment ‘Thou shalt not kill’ assumed its full meaning for the intellectuals.

But French Protestant intellectuals were in a duality between being opposed to German militarism, which legitimized the war, and sharing common religious beliefs with the enemy.

God’s law or the Nation’s law?

Unable to choose either patriotism or religion, intellectuals decided to take part in the war effort, on the front line or behind, while preserving their religious integrity. All followed ‘their own conscience’.

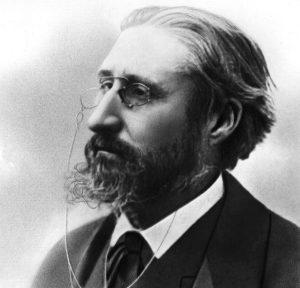

Charles Gide (1847-1932), a university professor of political economy was too old to be mobilized in 1914, but both his sons served. Paul, the elder, died for France in 1915 and Edouard, the younger, was severely wounded. In C. Gides’s view, each individual had to find his spiritual path while remaining a patriot, and still be coherent with his personal values.

Jules Puech (1873-1957), Doctor of law and assistant editorial secretary of the magazine La Paix par le droit (Peace through right), voluntarily enlisted in the infantry in 1915. According to him, the absence of God combined with the waning of patriotism induced stronger bonds between men.

André Chamson’s 1925 book Roux le bandit (Roux the bandit) portrays ‘a highlander who refuses the Common Law to follow what is for him the Divine Law’. For Roux the law should follow a religious ideals which is are above those of the country, the priority, however for most intellectuals was to maintain personal integrity.

Identifying with the others

Understanding, acting, sharing the same war effort as the people was paramount for some intellectuals. Indeed, for them talking about the war without having experienced it was inconceivable. Jules Puech and Jean Norton Cru (1879-1949) had personal experience of it. Having fought for the French Nation, they had other views and other thoughts than their comrades who had stayed in Paris. Both had felt useful in the effort, even though they were not the best of comrades they had provided ; help and support by writing to their loved ones, asking the officers for information … J.N. Cru talked about ‘empathy’ for his comrades. So that each could remain true, the fundamental value was respect.

Like Jean Norton, Jules Puech reminded people of the importance of disclosing the life stories of such different men united in the trench war.

The evolution in the notion of warfare

Upon the call to the front in 1914, men were mobilized to defeat militarist Germany. Each started with his ‘share of hatred for the enemy’, but ended with a totally different vision.

The militarized German nation, who was held responsible for the war, no longer seemed the only trigger of the conflict. The very notion of patriotism was questioned, which had never been the case before. For instance, Jules Puech mentioned the nonsense of the war launched by ‘4 or 5 idiots or bandits who made millions of men lose at least one year of their lives, but and sometimes even their lives’.

Peace and victory, as soon as possible, were longed for even though intellectuals were aware that the victory ideal was complex, because propaganda never mirrored the reality of war. Men were out of breath, physically as well as psychologically, and the cause defended by their country no longer satisfied them. Living with ‘mobilization, cruelty and patriotism’ made them understand they had been ‘mislead’.

War changes men, and men change war through their constant personal questionning, but mainly through their actions.