Alsace was made up of several different interconnecting territories

At the beginning of the 17th century, the possessions of the Catholic Church in Alsace consisted of several different interconnecting territories.

In the 16th century, vast areas made up catholic ecclesiastical territory. The bishopric of Strasbourg included half the Lower Rhine and some parts of the Upper Rhine. The bishop of Bâle in the south and the bishop of Spire in the north also possessed land in Alsace. The Habsbourg estate included two thirds of the Upper Rhine and the dukes of Lorraine also owned land in Alsace.

The house of Wurtemberg, however, which was favourable to the Reform Movement, owned land in the Upper Rhine, as well as various different branches of the house of the Palatinate. Strasbourg was a special case : since the XIIth century it had been a free town, independent of the Catholic Church and was only loyal to the Emperor ; under Bucer’s influence, the town soon joined the Lutheran movement.

The different stages leading to the return of Alsace to France

By the end of the Thirty Years War (which lasted until the middle of the 17th century) France had taken possession of many territories in Alsace. The Thirty Years War finally came to an end with the Treaty of Westphalis (1648). The conditions were:

- The treaty of Osnabruck, signed by Sweden (which was protestant) and the Austrian empire (which was catholic). In this treaty the members of each religion were allowed to recuperate the land which had been in their possession on 1st January 1624.

- The treaty of Munster, signed by France and the Empire. In this treaty, France retook possession of the three bishoprics (Metz, Toul, Verdun) as well as the Habsbourg estate : Haute Alsace and the “langrave” of Haguenau, that is to say, most of Alsace, apart from Strasbourg. However, certain clauses were obscure. Indeed, according to the treaty, the king had to maintain in his territory « the Catholic religion in the same way as the princes of Austria had maintained it before him and that he should ban any new religion which had been introduced during the war », thus the principle Cujus regio, ejus religio was faithfully adhered to. However, the treaty also stipulated that in the regions where there had been religious tolerance before 1624, this condition did not apply. What’s more, those who had adhered to the « so called Reformed religion » were to be given freedom of worship – religious persecution was forbidden and the Lutherans were allowed to keep the possessions of the Catholic Church which they had owned before the Ist January 1624.

The king, in fact, according to the treaty, only maintained possession of the territory which had formerly belonged to the Austrians and this did not include Strasbourg and the free imperial towns of the Décapole (Mulhouse, Colmar, Munster, Turckheim, Kayserberg, Sélestat, Obernai, Rosheim,Haguenau, Wissembourg). The inhabitants of these towns refused to swear loyalty to the French king and would not even open their doors to the duke of Mazarin, the nephew of the Cardinal and grand bailiff of Alsace. But the treaty of Nimègue (1678), which put an end to the Dutch war, obliged these towns to join the kingdom of France. From 1679, Louis XIV proceeded in truly Machiavellian style, as can be seen from the following : he insisted on the fact that according to the treaties of Westphalia, not only was he given land and towns, but also the dependent territories which accompanied them. Thus, the policy of « reuniting territory » enabled the French Crown to take possession of the principality of Montbéliard (which had belonged to the dukes of Wurtemberg), the territories of Germescheim, Lauterbourg, the duchy of Deux-Ponts, Forbach and other places in the Sarre. What was even more spectacular was the fact that in September 1681, Strasbourg surrendered to Louvois, without so much as a single cannon being fired, quite by surprise and at a time when there were no hostilities. Alsace and France were definitely reunited (except for Mulhouse which became part of the French kingdom in 1798) shortly before the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, thus stunting the growth of Protestantism in Alsace.

However, the treaty of Ryswick (1697) put an end to the league of Augsbourg and also to Louis XIV’s policy of imperialism. Indeed, he was forced to surrender all the bridgeheads situated on the right bank of the Rhine, which had formerly belonged to France.

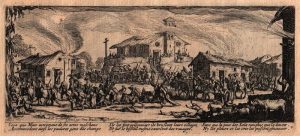

A repressive policy

At the surrender of Strasbourg, Louvois (minister for war and responsible for governing Alsace) had agreed to respect the rights of Protestants, as was stipulated in the treaty of Munster. However, when the catholic mass was celebrated anew in Strasbourg cathedral in the presence of Louis XIV, this symbolic act was done deliberately to show the inhabitants that their town was no longer a Protestant stronghold. The Jesuits were instructed to set up a seminary for future religious ministers in the province and soon afterwards they also set up a college for young people who were not destined for the Church.

Other measures followed which were more repressive than before. For example in communes where any Catholics at all had been registered, even if they had been few in number, Lutherans or Calvinists were not allowed freedom of worship ; Jesuits and Capuchins were allowed to distribute religious propaganda without restraint ; any citizen who denigrated the Catholic religion was severely punished ; all these decrees could incur the confiscation of goods or banishment from the town.

On the other hand, new converts to Catholicism were given many advantages and Catholics coming from other regions were warmly welcomed. In many Protestant churches, the sharing of the place of worship or “simultaneum” was made compulsory. In Strasbourg it was with the greatest difficulty that two of the main Lutheran churches, Saint Thomas and Saint Guillaume, managed to resist the implementation of such a policy. The most shocking of these decrees concerned free towns where the population was entirely Protestant or partly Protestant and partly Catholic. In such places, the councils had to consist of as many Catholics as there were Protestants, even if only a few Catholic members were concerned. It is difficult to know how many Protestants converted to Catholicism – in 1697 there were 5000 Catholics and 21000 protestants.

Mercifully for the Protestants, when Louvois died in 1693, the government of the province by the French Crown became less repressive than during his lifetime.