The Bible crossed French frontiers

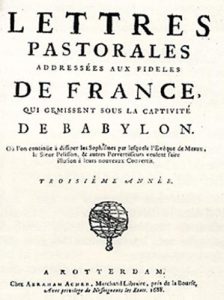

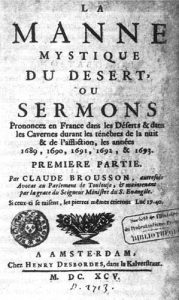

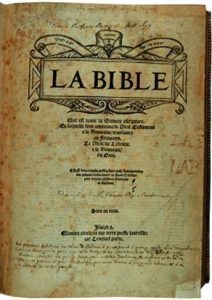

After the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, a decree was issued by royal council on 9th July 1685 forbidding any Protestant bookseller or printer to continue his professional activity. As a result many fled to Protestant countries and it was no longer possible to print the Geneva Bible in France. However, Bibles were printed in Geneva, Amsterdam and Leyden as well as books written with the aim of strengthening the Protestant faith of those who had renounced their faith and remained in France (Les Lettres Pastorales by Jurieu in 1686 and Claude Brousson’s Lettres aux Catholiques Romaines in 1688, which ran to 10,000 copies). Sometimes liturgies or sermons were printed for communities without a pastor. All these texts were smuggled into France and distributed in spite of the difficulties.

The hidden Bible

In October 1685, the Edict of Fontainebleau (or the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes) made it illegal to follow the Reformed faith in France. Some Protestants fled to Protestant countries. Many renounced their faith, under threats from soldiers. They were called the “new converts“. However, many continued to read the Bible and to sing psalms in secret.

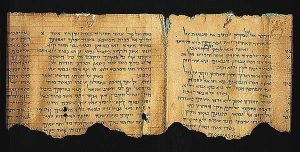

However, on the 6th September 1685, the Paris Parliament forbade anybody to read the Bible and the Geneva New Testament (that is to say the Olivetan Bible which had been revised in Geneva). All police officers were ordered to undertake searches “in printing firms, booksellers, as well as in the homes of ministers and elders” (that is to say in the homes of pastors and leaders of the Protestant communities). So, to own a Bible was dangerous – it was a sign that one was not a good Catholic and could be punished by prosecution, a fine or even imprisonment.

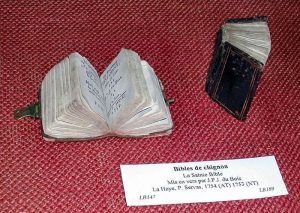

Thus the “new converts” had to hide their Bibles – this could be in a variety of places : behind a mirror, under a stool, in the wall. Another solution was to have a tiny Bible called a “chignon Bible” which women could easily hide in their buns.

Many of the soldiers undertaking the searches in the homes of the “new converts” could not read. Their officers had taught them to recognize the first page of the Geneva Bible. So the “new converts” tore off this offending page and the soldiers were unable to recognize it.

All these stratagems enabled many families to keep their Bible at home and continue reading it. This was often with other members of the family or neighbors. Their children had to follow a Roman Catholic catechism during the day, but in the evenings they would “unlearn” their lessons as they listened to the Bible being read and the Psalms being sung at their family service.

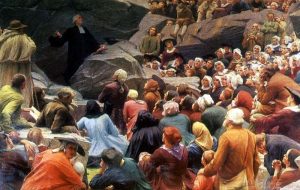

Preaching from the Bible

Protestants were not allowed to worship in public after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, but nonetheless the “new converts” continued to gather together in isolated places, sometimes at night, in order to hear a preacher. If they were caught, the men could be sent to the galleys and the women and girls to prison or to a convent ; as for the preacher he could be hung on the gallows. At the end of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th century, many Protestants died for their faith. However, the risk of danger did not prevent the “Protestants” from wanting to hear Biblical sermons or learning more about the Scriptures. For them the Bible had become the Word of Life for every day and the Word of Comfort in times of difficulty.

As the pastors had received orders to leave the kingdom within a fortnight of the issue of the Edict of Fontainebleau, laymen called “preachers” would often read sermons which had been printed before 1685 or in the Refuge countries. The king’s soldiers searched for them without ceasing and they were all too often sent to the gallows, tortured on the wheel or forced to go into exile ; the “prophets”took their place.

The Bible and Prophesy

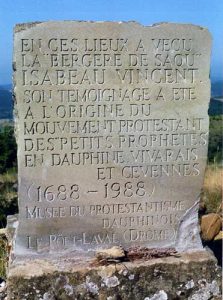

In 1688, in the Dauphiné a strange Protestant movement emerged : prophetism. A young shepherdess, Isabeau Vincent talked in her sleep, first in the local dialect and afterwards in French. She recited Bible verses one after the other which suited the circumstances of the time perfectly. “Hold fast – seek the Word of God – you will find it if you repent”. A crowd gathered round to listen. This movement called the “minor prophets” spread throughout the Vivarais region and later reached the Cevennes. Many of these prophets were young people, both boys and girls. Nearly all of them were illiterate and only spoke the local dialect, which is why it was so surprising that they should prophesy in French. An explanation could be that they had memorised the texts of the Bible when it was read aloud in French.

The “minor prophets” mostly called the faithful to beware of the Roman Catholic Church, nicknamed “Great Babylon”. They told the “new converts” to return to their Protestant faith and refuse to go to mass. The short, succinct phrases uttered by the Biblical prophets (“Leave Babylon”, “Return to God”) deeply impressed the Protestants in the Cevennes and were the origin of their armed rebellion called the War of the Camisards (1702-1704).

Studying the Bible

After the War of the Camisards, the “new converts” put an end to any violence and the prophetism movement lost its momentum little by little. After the death of Louis XIV, and under the influence of Antoine Court, Protestants began once more to hold secret meetings. The spontaneity of the prophetic movement was replaced by a more cautious organisation of Protestant communities and a return to the discipline of the Reformed Churches.

Antoine Court set up a divinity school in 1726 in Lausanne to give theological instruction to the pastors of the “Desert Church” (pastors who lived an underground existence and who had to spend their time in hiding). The teaching was mostly devoted to Bible Study. Many of the pastors who received this instruction in Switzerland fared badly when they went back to France ; they were frequently condemned and shot. The last of the executions was pastor Rochette who was put to death in Toulouse in 1762.

After 1760 France became a more tolerant country, but freedom of worship was not re-established until 1789.