The Reform movement encouraged women to impose themselves in society

It was because they needed to consult the Bible to learn about God’s will for their daily lives and to “bring up their children in a Christian way” that protestant women had to learn how to read. According to Luther, schools were necessary to teach girls as they would be future mothers and according to Calvin, the mother had the same responsibility as the father concerning the upbringing of the children, which had to be both kindly and wise.

For this reason, in families belonging to the Reform movement, as early as the XVIth century, the daughters received a better education than their catholic counterparts, even if they came from a poor background. Many girls’ schools were opened in Béarn, but also in strongly protestant towns like Nîmes, La Rochelle and Montauban.

They were taught how to become future wives and mothers ; they were also instructed in the running of a household, which necessitated learning to read, write and do arithmetic. It was extremely unusual at this time for girls to be educated in this way.

From 1550 onwards, women could be seen holding prayer meetings, christening children and preaching.

This did not last long, though. From 1560 onwards, they were no longer allowed to participate in such a way in Church life. At the provincial and national synods, decisions were taken forbidding them from “meddling with Bible readings, prayers and christenings.”

The protestant Churches also gave preference to men when choosing positions of authority.

Colleges of secondary education -14 were founded between 1560 and 1598- were only open to boys and girls were simply trained to be good housewives.

As for their attitude, they were told “to be calm, modest and avoid any outrageous behaviour” :

“As long as she lives,

She must seek her husband’s pleasure

And be in perfect control of all she does

So that she should never do anything

Which displeases him.”

Théodore de Bèze

This is how women’s new role came into being in protestant sociology. No longer was she placed in an uneasy position between two extremes, the prostitute on one hand, the virgin on the other, as in the Middle Ages. She was most definitely “called by God”, that favourite expression of Luther’s, and was, in the eyes of God, as important as her husband.

Naturally, protestant women were expected to run their households, to care for their children and to bring them up to the best of their abilities. This has always been the case, but with the Reform movement, they were seen as key factors, from the religious point of view, in the accomplishing of God’s will and from the political point of view, in the establishing of an ordered society.In the couple, it was true, she took second place, but this was not to say that she played a secondary role : she made an active contribution to the marriage and the harmonious development of the family. This new role gave her a sense of dignity and value which she had never had before.

The emancipation of women

Historically, little is known about women in the protestant community, who lived out their lives in all modesty and humility. But we can guess that, due to the Reform movement, new horizons were gradually opened up, indeed, the most sacred and vital religious activity for a protestant, the study and commentary of the Bible, now became possible for them. No longer were they under the complete control of their pastors and husbands, from this time on they were considered as responsible human beings.

This was especially true of the wives of the nobility from the beginning of the XVIth century onwards. They benefited from a good education and lived in cultured circles ; not only did they aspire to more knowledge to deepen their own faith, they were also keen to discover the new ideas of the Reform movement with a view to sharing them with others.

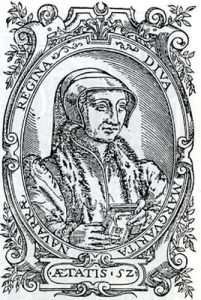

Marguerite d'Angoulême (1492-1549)

Marguerite d’Angoulême was François Ier’s sister and her second husband was Henri d’Albret, the king of Navarre. She was at the centre of a lively intellectual circle at court and followed the religious ideas of her time with interest, especially those of Guillaume de Briçonnet, bishop of Meaux and Jacques Lefèvre d’Etaples, a great humanist, both of whom advocated religious reform. She was the mother of Jeanne d’Albret.

Renée de France (1510-1575)

Renée de France was the second daughter of Louis XII and Anne de Bretagne, (her elder sister, Claude de France, married François d’Angoulême who later became François Ier). She went even further in the study of the new ideas of the Reform movement. In the austere duchy of Ferrare – she had married Hercule d’Este, duc de Ferrare – in 1535 she invited Clément Marot, who had fallen into disfavour with the king because of the “Affaire des Placards” and especially Calvin, who had been obliged to lead a wandering, poverty-stricken life, between Bâle and Geneva, after the publication of his Institution de la religion chrétienne.

Renée never, however, renounced her catholic faith – this was in spite of Calvin’s influence on her (they wrote to each other until she died), in spite of the violence of the religious wars and the horrors of the St. Barthélemy massacre, which she witnessed at first hand since she had come to Paris for the wedding of Henri de Navarre and Marguerite de Valois.

Isabeau d'Albret (1513-1560)

She was the daughter of Jean d’Albret and Catherine de Foix and married René Ier de Rohan. She met the admiral de Coligny in 1556 and was in Béarn when his niece, Jeanne d’Albret, introduced Protestantism into the area. Although she was very attracted to the ideas of the Reform movement, she did not give up Catholicism until after her husband’s death in 1558, out of respect for his faith. Then she introduced Protestantism to her family in the château of Blain and established the first protestant Church in Brittany.

Charlotte de Laval (from about 1520 to 1568)

She was the wife of Gaspard de Coligny and gave her unshakeable support to him throughout all his conflicts.

Jeanne d'Albret (1528-1572)

She married Antoine de Bourbon and became the Queen of Navarre in 1555 when her father died ; she converted to Protestantism in 1560 under the influence of Théodore de Bèze and it became the official religion throughout her kingdom. She was the mother of Henri IV and died in Paris, having come there for the wedding of he son to Marguerite de Valois, Charles IX’s sister.

Charlotte Arbaleste (1550-1606)

She was the wife of Philippe Duplessis-Mornay. Their marriage was one of faith and affection for each other and she gave him her full support in all his political and religious undertakings.

Catherine de Parthenay (1554-1631)

Catherine was from a well-established protestant family in Poitou. She was a wealthy heiress, whose second husband was René Vicomte de Rohan, with whom she had five children. One of these became Henri II, the future duc de Rohan, who became the leader of the Huguenots after the death of Henri IV (1610).

Catherine was proud to belong to this noble family and brought up her children in the protestant faith – indeed, in Brittany her château was a stronghold of the reformed faith.

At the time of the siege of La Rochelle, she remained with her daughter amongst the other Protestants trapped within the city. She managed to survive, together with five thousand others, but was later locked up in the prison of Niort. As a result of the treaty of Alès in 1629 she was released and died in the Parc de Soubise in 1631.

There were other very brave women who bore witness to their faith when they were drawn into exceptional circumstances because of their husbands’ political or religious loyalties.

Claude du Chastel (1554-15887)

Although Claude was a strong protestant, she was also very much in love with Charles de Goyon, who was a catholic. Their relationship was a tempestuous one due to the religious wars, which caused havoc at this time. Claude had to become a catholic in order to marry him, at the château de Gaillon, but when the couple returned to Brittany they openly declared their protestant faith.

Women during the period of religious persecution

From the beginning of the XVIIth century until the Revocation of the edict of Nantes(1665), and all through the XVIIIth century until the edict of Tolerance (1787), the French reformed Church was crushed and nearly annihilated by the State. As the men had to submit to authority in order to keep their jobs and protect their families, it was the womenfolk that passed on the protestant faith and its values from one generation to another.

At the time of the Revocation, many couples were torn between Catholicism (the husband wished to deny his reformed faith) and Protestantism (his wife did not want to give up the faith which had been dear to her since childhood).

During the Camisard Revolt, it was the women preachers and prophets who stirred up the religious faith and fighting spirit of the rebels.

However, one woman stands out above all the others, and this is Marie Durand (1712-1776)

who was imprisoned for 38 years in the Tour de Constance because she refused to abjure her Protestantism. She was the symbol of loyalty to the reformed faith.

The influence of the Revival movement

From the end of the XVIIIth century and all through the XIXth century, the Revival movement had a great influence on the faith of protestant women and led them to take an active part in helping the victims of society. In particular, they supported women in distress, sought to provide them with better education and fight for their rights.

They often came from bourgeois backgrounds and as protestants reintegrating French society (after years of rejection) they led lives of impeccably high moral standards, inspired and strengthened by their reformed faith. They were active members of the society of their day, creating associations which were ahead of their time in such areas as education, sanitation and even politics.

The example of Mme. Jules Mallet (1794-1856)

Madame Jules Mallet was a woman of great moral integrity who spent her life helping children, prisoners and the sick.

She was the daughter of Christophe Oberkampf, who had founded the factory which produced the famous Toile de Jouy, (a kind of printed cotton). Her father-in-law was Guillaume Mallet, the manager of the Banque de France. In 1826, she opened several infants’ schools, inspired by the English model ; these “shelters” were the nursery schools of the future, taking in children from 2 to 6 years old, mostly from working-class backgrounds.

During the cholera epidemics of 1832 and 1849, she took children into her own home and later kept them in a building which she rented out in Jouy-en-Josas.

In 1838, she organized a committee of women who visited the St. Lazare prison and helped to develop the charity which cared for those coming out of prison, run by the Diaconesses.

Emilie Mallet was a model wife and mother. However, in addition to this, she wanted to witness to her faith, (which was strongly influenced by the Revival movement) in all her activities. She took on positions of responsibility in society, involving other women of her social level as well. In fact, she instigated an awareness of social problems which led other wives of prominent businessmen to take part in associations to help those in need.

Women's contribution to social work in XIXth century society

In the middle of the XIXth century, protestant women were influenced by the works of charity carried out by anglo-saxon women and the theories of Saint-Simon (1760-1825) on “social humanism”. They became much involved in the great issues of social reform which were being discussed at that time.

They also followed the example of their American and Swiss counterparts when they sought to implement new laws governing prostitution.

Jenny d’Héricourt (1809-1875), Henriette de Will-Guizot (1829-1906), Mme Jules Siegfried (1848-1922) and others played an active part in associations or publications which became more and more well-known and respected :

- The Society Of Christian Morality, which helped the inmates of the St. Lazare prison,

- Women’s Voice – a feminist daily newspaper which called for political equality between men and women,

- The Society For The Emancipation Of Women ; this called for the financial independence of women, provided by work which should be made available to them.

- The Union Of Young Girls’ Friends ; in 1877 the Parisian section of this movement, (founded in Geneva in 1877) came into being. It militated against prostitution and the white slave trade.

All these associations run by protestant women ultimately led to the founding of the National Women’s Congress. This was the sign that the days of philanthropy were over – it was political and social action which concerned protestant women from this time onwards.