The need for civil peace

Organising a new political regime through his coup on brumaire 18 (the 9th of November 1799), Bonaparte’s aim was to achieve civil peace, and he deemed religious policies very important. He was an agnostic who did not know much about Protestantism, but considered it favourably (« we wish all the people were Protestant », he said in 1801…) to outweigh Catholicism which he would not accept as the dominant religion, contrary to what the Pope wished, but called it the « religion of the vast majority of French citizens ».

The Concordat, concluded with Pope Pius VII, was signed on the 8th of September 1801, but was not readily enforced, and only became a law on the 8th of April 1802 (18 germinal year X) after the Organic Articles – ruling the Catholic church and organising the Protestant worship – had been added by Bonaparte himself. The Jewish community was to be dealt with later, which was justified by the fact that the Jews were rather a people than a religion, and their worship was to be reorganised in 1808.

Nevertheless it was not a negotiated law, but a governmental decision – indeed the minister in charge, Mister Portalis, had talked with a few Lutheran or reformed leaders, notably with pastor Paul-Henri Nahon and with a member of the legislative body Pierre-Antoine Rabaut-Dupui, but never took their opinion into account. Actually Bonaparte’s goal was not to reinstall the Protestant church -especially its reformed movement- into its pre-persecution status. He changed its organisation, causing a lot of difficulties and conflicts.

The 1598 synod was partly forgotten

The new organisation of the reformed church upset various aspects of its traditional organisation, namely :

- In the 16th century the reformed church followed the so-called « synodal presbyterian » model « based on the assembly of the members of the local church who voted for their consistorial representatives, or elders’ council (presbyters), renewed through co-option. The consistory chose the pastor and president, and also its representatives at the « colloquy » ,i.e. the assembly of representatives of a few local churches. The elders also elected delegates to the particular -or provincial- synod. The assembly of representatives at the particular synod was called the general synod. The regional synod dealt with regional disciplinary matters, and the general synod was the upper instance and held doctrinal authority. To conform to the logic of universal priesthood, the assemblies comprised lay people and pastors.

- Bonaparte’s laws ignored local churches, and favoured « consistorial » churches with « six thousand similar worshippers », as in a Catholic parish. The Protestants being spread out, consistorial churches comprised several local churches, thus creating a hierarchy, which is contrary to the traditional equability among local churches. Moreover « particular » synods alone were considered, and required a government leave to meet, which was never to be granted. But foremost, the law did not mention the general synod which was the only authority in dogmatic and disciplinary matters – the body of reformed churches was thus left without a head. Finally, the State interfered with religious matters, indeed article 4 stipulating that no doctrinal or dogmatic decision, especially no confession of faith, could be published or taught without governmental consent.

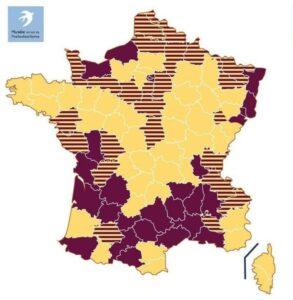

- In 1802, 81 consistorial churches were founded and 19 oratorial churches with very small congregations or in areas without a consistory. Local churches did not disappear, but had no official status, and the pastor was to be chosen by the consistory. Its lay members, chosen for four years, were co-opted among the wealthier citizens, which was contrary to the democratic standpoint of reformed Protestantism. As Pastor Pédézert wrote later on : « Neither the apostles nor Jesus-Christ could have become electors or been elected in the church designed by Napoleon and his ministers. » The general synod was ignored, and the reformed church was run by eminent citizens.

The Protestants, however, welcomed that status which acknowledged their existence and held no restrictive measures n comparison with the catholics,. As pastors played an official rôle, they could be asked to take part in public ceremonies. They were to be paid by the State for the first time. So churches could build up their fellowship, notably their religious structure. In addition to the Lutheran theological faculty in Strasbourg, and to the one in Geneva annexed to the Empire, a reformed faculty was to be created in Montauban. In 1814, the pastoral community, weakened after 1792, was renewed with 214 positions opened to reformed pastors, almost twice as many as in 1802.

Adjustment problems

Problems progressively appeared all caused by this ill-adjusted law, namely :

- Discipline and synods – the discipline of reformed churches was a standardising text written in 1559, a sort of constitution to rule the life of the Church, its material and spiritual organisation. The Concordat admitted the Discipline but it was difficult to implement. Indeed, the consistory was the only authority, generally composed of eminent people (who did not represent the majority of protestants), and besides there was no structure for consistories to meet – no national synod being devised by the law, and particular/ regional synods not being allowed to hold sessions. In the Drôme region a modest attempt was made between 1848 and 1853, but no meeting of all particular synods was ever held. So the question was raised as to which authority was in charge of enforcing the Discipline, there being no synod ?

- Local churches, according to the reformed tradition played a basic role of living quarters for their members, and of foundation for the pyramidal structure of the reformed church composed of the assemblies. But the Germinal law ignored local churches, and did not acknowledge their very essence.

Means to claim a Protestant identity

In order to create structures within which common problems could be discussed on a national level, even unofficially, some contrivances were devised, such as :

- the creation of various religious associations, the main ones being the Société biblique protestante de Paris (1818), Société des Traités religieux (1821), Société des missions evangéliques (1822), Comité pour l’Encouragement des Ecoles du Dimanche – committee in favour of Sunday Schools (1826), Société pour l’Encouragement de l’Instruction Primaire parmi les protestants de France – association in favour of Primary Education among French protestants (1829), Société Evangélique de France (1833), and from 1835 on various associations merged in 1847 under the name « Société Centrale Protestante de France ». All these organisations were generally run by wealthy and devoted lay people.

- The organisation named Conférences pastorales led by Jean Monod in Paris and Samuel Vincent in Nîmes played an important role in discussing problems, but could not replace synods as they had no ruling power.

Until 1848 as long as the huguenots were not too disunited, the debate on dogma could exist. But in the following years the lack of a central authority and the hard lines led to a split.