The background

From 1661 on, Louis XIV gradually shredded the Edict of Nantes, which had been signed by Henri IV in 1598. He gradually banned Reformed Protestants from working in most trades and had the churches pulled down one by one. In October 1685, only a score of Reformed churches remained active.

The use of violence (as early as 1681 in Poitou) forced the Protestants to recant. They converted in droves as they were terrorised by the “dragonnades”. The atrocities began in May 1685 in Bearn, then Languedoc, Dauphiné, Aunis, Saintonge, Poitou. News of victory spread to the Court : most of France had turned Catholic.

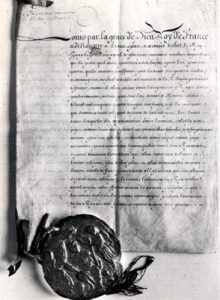

So, on October 1685, Louis XIV signed the Edict of Fontainebleau which repealed the Edict of Nantes.

The introduction to the Edict

Louis XIV, in his long introduction, praised his ancestor, Henri IV, for trying to bring the Protestants back to the Catholic Church, for the Edict of Nantes and subsequently the Edict of Nîmes (Alès peace treaty), which was only granted in order to calm tensions.

The premature death of Henri IV, and the numerous foreign wars that followed, prevented his goal from being achieved. Once peace was restored, Louis XIV endeavoured to achieve the aim. Since “the largest part of the alleged Reformed Church (RPR) have converted to Catholicism, the Edict of Nantes has become useless”.

The content of the Edict

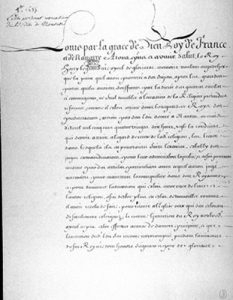

The Edict was made up of 12 articles :

1 : the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1598), signed by Henri IV, and the Edict of Nîmes (1629), signed by Louis XIII, so, consequently, the demolition of all the churches that were still standing.

2 and 3 : worship of the alleged Reformed Church was banned, including among the lords.

4 : the banishment, within two weeks, of pastors who did not want to convert – on pain of the galleys.

5 and 6 : inducements to get pastors to convert : life pensions and vocational retraining in the legal profession.

7 : ban on Protestant schools.

8 : obligation on members of the Reformed Church to have their children baptised and educated in the Catholic faith.

9 : confiscation of the possessions of Reformed Church members who had already gone abroad, unless they came back within a period of 4 months.

10 : ban on members of the Reformed Church emigrating – on pain of the galleys for men and prison for women.

11 : punishment of “new converts” who went back to Protestantism.

12 : permission for those who had not yet converted to reside in France, so long as they complied with the rules previously mentioned.

Achieving freedom of conscience

The last article of the Edict of Fontainebleau appeared to grant members of the Reformed Church freedom of conscience (if not freedom of worship). In fact, it never happened and many Protestants were jailed for refusing to recant. Moreover, “dragonnades” were still organised after the Edict of Fontainebleau, north of the Loire valley, to forcibly convert those who had not yet converted.

The ban on emigration was a unique case in European law of the seventeenth century. Indeed, the Edict of Fontainebleau forced dissidents (several hundreds of thousands) to convert to the king’s religion without even allowing them the small freedom of leaving the country.

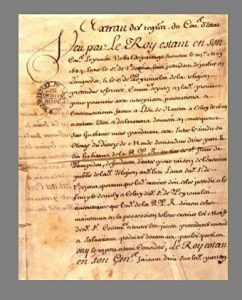

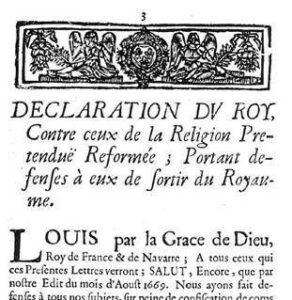

The royal declarations after the Edict

Numerous royal declarations reinforced or clarified the terms of the Edict until the end of the reign of Louis XIV.

Civil status posed a problem since the records of baptisms, marriages and deaths were kept by the “religious” ministers. Without pastors, how could the deaths of those who had not recanted be recorded ? In the face of this legal loophole, Louis XIV allowed deaths to be registered with the secular authorities from as early as 1695.

On their death beds, many “new converts” refused the Catholic sacrament of Extreme Unction and said they wanted to die in the Reformed religion. To prevent this, Louis XIV declared that those who survived after refusing to receive Extreme Unction would be sentenced to the galleys, in the case of men, and to prison for women. If they died, the corpse was dragged around the streets. But as early as the next year, the king asked that his representatives be lenient in enforcing this measure.

A declaration dating back to January 1686 declares that all the children of Protestant families, between the ages of five and sixteen, should be placed in the custody of Catholic parents or, if not, of any Catholic person appointed by the judge.

A declaration dated December 13, 1698 demanded closer supervision of the “new converts” :

- attendance at mass and Catholic practices was virtually compulsory for lords and nobility,

- there was an obligation to get married in church and to have one’s children baptised within 24 hours of birth,

- there was an obligation to present a certificate certifying one’s good Catholic behaviour, signed by the priest, in order to get legal assistance, or a law or medical degree.

This same declaration demanded parishes open primary schools for the children of the “new converts”. The king had serious doubts about converting adults but hoped to reach children through catechism and education.

In 1699, the ban on emigration for the RPR and “new converts” was reinforced.

Distress for the Protestant community

Those who had stayed in France, without churches, schools or pastors, were highly distressed. Religion structured their daily lives. Now this had collapsed, some analysed the tragedy in the light of the book of the Apocalypse.

The sudden and massive recanting, under pressure from the dragoons and the threat of loosing their children, engendered a feeling of collective guilt especially in overwhelmingly Protestant areas.

Protestants who did not convert by choice led a “double life” : they openly showed a minimum observation of Catholic rituals, but remained faithful to their religion and, in particular, read the Bible and sang Palms in the secrecy of their homes.

Passing their Reformed faith on to their children proved difficult as they had to send them to Catholic Catechism and Catholic schools. However, at night, some would undo the Catholic teaching.

In addition, hefty fines were levied on those who remained attached to the Reformed faith and did not observe Catholic rituals assiduously.

In the face of so much adversity, the Protestants wondered if the dragoons, the destruction of churches, the exiling of pastors were not signs of punishment for an ungodly people.