The first "dragonnade" in Poitou (1681)

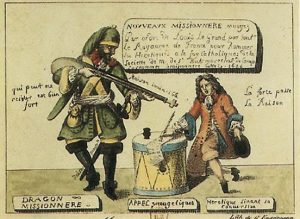

The king’s dragoons were sent throughout France in order to get heretics to convert to the Catholic faith. The Military were powerful, and the heretics recanted.

In 1681, the first dragonnade was tried in Poitou, the initiative of Intendent René de Marillac (Intendent in Poitou from 1677 to January 1682), who must have been encouraged by Louvois.

Louvois had sent a cavalry regiment to Poitou for winter quarters. Marillac lodged them mostly in Reformed homes and allowed them to plunder and to ruin their hosts. The dragoons forced their hosts to pay and feed them. When they ran out of money, the dragoons sold the furniture or broke it into pieces. If the Protestant host refused to convert, he was mistreated, hit and became a toy for these savages, who invented new torture methods and went as far as making children suffer. Women endured all kinds of torture. Once the unfortunate man had recanted, the dragoons went to the next home.

Within months, the priests registered 38,000 conversions. The Poitou area was ruined and its inhabitants fled to England or Holland. The news roused indignation in the Protestant community of Europe. The soldiers were recalled and Marillac was moved elsewhere.

The "dragonnades" before the Revocation (1685)

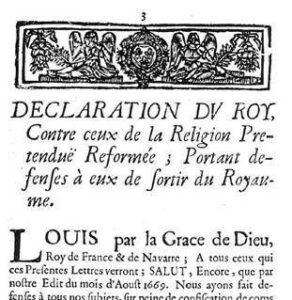

Even before the Revocation, Protestants were greatly persecuted.

The Truce of Ratisbon, signed in 1684, had rendered some of the troops “available”. In July 1685, Foucault, king’s Intendent in Pau, was allowed to use the soldiers against the Reformed community. He improved the system Marillac had begun in Poitou. As soon as the arrival of dragoons was announced, entire villages converted. Foucault announced thousands of conversions without any violence. He then went to Poitou, where he let the dragoons commit terrible abuse of all sorts.

As he was very successful, Louvois sent the dragoons to other Superintendents in other Provinces. The dragoons went to Bergerac, Montauban and then Castres, the Rhône valley and Dauphiné. In the face of the terror they provoked, the Reformed community in Montpellier and Nîmes recanted to prevent abuse and so did those in Cévennes : they converted before the arrival of the soldiers. Three quarters of the Huguenots recanted thanks to the “military missionaries”, that is the dragoons.

The "dragonnades" after the Revocation

In Lubéron, the Grignan county dragoons won over the Reformed communities around the villages of Lacoste, Mérindol, Lourmarin, Joucas, Cabrières, former Waldese strongholds.

Areas north of the Loire were under the control of the dragoons as well, but only after the Edict of Nantes.

Normandy, Brie and then Champagne were not spared either. In November 1685, the Northern and Eastern areas around Chartres, Rouen, Dieppe, Caen, and Nantes were attacked. Then it was the turn of the Meaux, Champagne, and Sedan dioceses.

In Rouen, at the end of October 1685, in four days of violence twelve companies forced the heads of households to recant. All the towns in the Caux area gave in and Le Havre surrendered before the arrival of the dragoons. Massive emigration to England and the Netherlands, through the “Anglo-Saxon Islands” (Channel Islands), caused a huge decrease in the local population.

The Brie area as far as Soissons came under the control of the dragoons in December 1685. But despite the efforts made by Bossuet, Bishop of Meaux, urging the “new converts” to stay faithful, Protestantism never completely disappeared from the region.

The Treaties of Westphalia had considered the Reformed community in Metz somewhat differently and Louis XIV had granted them an extra ten months to convert following the Edict of Fontainbleau (1685). Metz was the last city in France to be under the control of the dragoons in August 1686. In less than three days, Metz gave in and deportation put an end to resistance in 1687.

However, despite the violence caused by the “dragonnades”, the spirit of the Reformed Church survived and the apparent new converts (N.C.) soon organised resistance.