The principle of laity was not a problem for the Protestants

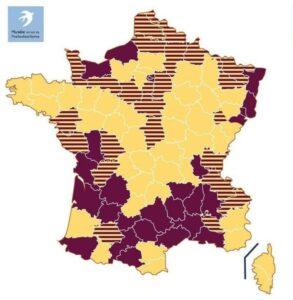

The separation of Church and State was easy to accept for the Protestants. Being a minority used to being wary of the State, they too had suffered from catholic supremacy, that was still very strong during the Ordre Moral period between 1873 and 1876. Some Protestants were probably quite satisfied that the Catholic church be submitted to the common law, as other organisations were. Moreover, a restricted minority was already independent from the State : the evangelical churches outside the Concordat.

Unanimity certainly did not exist – Lutherans were rather hostile, reformed liberals too, whereas the reformed orthodox, closer to the « left-wingers », were rather favourable, or at least uncomplaining. As for the ecclesiastical bodies, they would not officially take sides, confronted as they were to the « hostile trend towards incredulity prevailing in France » (W. Monod). The Dreyfus case and the anti-Semitic campaign, the actions against congregations, the national congress of Free Thinkers, anti-clerical campaigns made the separation seem like a victory of anti-Christianity.

But on the whole, the Protestants felt closer to the republicans, even more so as a campaign against Protestantism was launched in the 1890s in clerical and nationalist anti-Dreyfus newspapers.

In the Spring of 1895, to stand fast and get ready for the separation, an assembly of orthodox reformed Protestants suggested holding a Protestant meeting, which was to be the first general assembly of the reformed that took place in Lyon in 1896 to be followed by one in 1989.

The leaders of the orthodox reformed movement, who were given reliable information by Eugène Réveillaud (1851-1935) -a radical MP- and his son Jean -a member of Emile Combes’ cabinet – and also by Louis Méjean (1874-1955) – a collaborator of Aristide Briant – were able to modify the text of the law and allowed unions of worship associations, not only on a local but on a national level. Indeed for the evangelical movement keeping a national structure, the synod, to prevent “unrest” was of paramount importance.

Alsace, then a German region, was not affected by this law and was to keep its special status after the reunification.