Freedom of conscience became more widespread

Due to the influence of the philosophers of the Enlightenment, the rulers became more tolerant. This period was one of a certain acceptance of other religions, qualified by the historian Daniel Roche as “intelligent absolutism”.

It was becoming more and more clear that the Protestants had a perfect right to become full members of the state. Two people supported this idea, Turgot, general financial controller and also Maleshebes, appointed on 20th July 1775 as State Secretary of the king, dealing with the case of the Protestants.

There was less and less repression against the Protestants

Although French Protestants still lived under the threat of repressive decrees issued at the time of the Edict of Fontainebleau in 1685 (the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes) and despite the fact that the law had not changed (in 1724 Louis XV renewed the harsh rules of the Edict of Fontainebleau) nevertheless, the actual application of the laws was less strict : the punishments were less heavy and the restrictions less harsh.

The “new converts” were no longer forced to take part in Catholic sacraments and instruction.

As far as marriage was concerned, from 1760 onwards many parliamentary decrees did indeed recognize as true inheritors the children of Protestants who had not been married according to the “solemn rites” of the Catholic Church.

Little by little, reformed parents were no longer described as “concubines” or “fiancés” in the baptism records of the Church.

The Seven Year War (1756-1763) also contributed to a more tolerant approach because many soldiers were needed outside France, so there were less of them available to cause trouble to the “new converts”.

However, all was not well. An atmosphere of insecurity prevailed, the Protestants still lived under constraint, much as before, it depended very much on their local authority whether they were well treated or not. They could be harassed, fined or arrested at any moment.

During the reign of Louis XVth, 200 Huguenots were sentenced to slave-ships (whereas there are records of 1500 cases in the reign of Louis XIVth). It was due to the intervention of Court de Gébelin, general deputy of the Reformed Churches, that the last slaves were freed and that was not until 1775. Also, it was only in January 1769 that the last prisoner of the Tour de Constance was freed.

From the legal point of view, protestants were still barred from holding jobs in public service or local government.

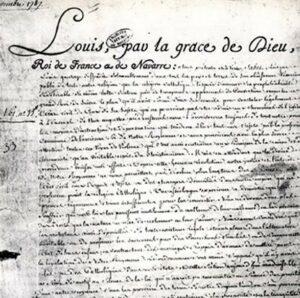

In the Edict of Tolerance (1787), with the “civil tolerance” they were recognized as having full citizenship as French subjects but were not yet able to have freedom of worship or hold positions of responsibility.

…the situation remained dangerous for protestants

Certain facts showed that the king could still threaten protestants with terrible punishments.

Pastor François Rochette was sentenced to hang on 18th February 1762 in Toulouse (he was the last pastor to be condemned to death) ; the Grenier brothers, three noblemen, glassblowers by profession, who had tried to save his life in Caussade, were beheaded.

The Calas issue : Jean Calas was sentenced to death by torture on the wheel on 10th March 1762 ; he had been unjustly accused of inflicting death on his son for religious reasons : it had been assumed by the authorities that the boy’s abjuration of his protestant faith had been the motive of the crime.

But there was another, positive aspect to the Calas issue : in 1765 Voltaire intervened at a high level to get the case reviewed by the court and Calas’ innocence proved – this had a great impact on public opinion at the time.

The Church gradually reorganized its structure

Despite the continuing repression and impossibility of public worship, there were more and more secret assemblies, under the influence of Antoine Court, so much so that the authorities had difficulty in controlling them.

Little by little, provincial and national synods developped, from the first national synod, held in the Vivarais in 1726, until the national synod of 1763, which gathered together the 19 delegates of the provincial synods. The former “map of protestantism” began to take shape again. However, it was difficult to establish contact between the various organizations as each community tended to be independent and was administered by lay members who were often important figures of the local community.

The “Désert” Churches increased in number and social importance. From 1760 on wards more and more pastors were active in this underground movement, there were 100 in 1770 compared to 180 in 1788. There was a certain safety in the fact that they no longer moved around from place to place but led a more settled existence. Most of them had studied theology in the Lausanne seminary.

Court de Gebelin, the son of Antoine Court, was appointed general deputy of the Churches by the national synod in 1763 and took up his position in Paris. He was responsible for the dealings of the Churches with the civil authorities.

He was succeeded by Rabaut-Saint-Etienne in 1784, who negotiated the edict of Tolerance in 1787.