Fertile ground

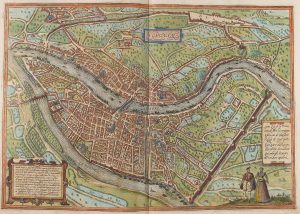

In the late 15th century, Lyon was the economic capital of the Kingdom, open to the outside. Fairs, trade and banking held by Italian merchants, and then by the German and Swiss, established the city in a European network where new ideas spread. The Consulate, the lay authority of the city, carefully treated the more or less usurer merchants, sometimes also accused of heresy. As the local power was weak, and no Parliament, no Faculty of Theology could single out the heretics, often considered as unimportant protest people. The main authorities, cardinals and bishops followed one another at a pace too fast to solve the opposition between the Consulate and the clergy, which developed an anticlerical climate. The Consulate had a very cautious attitude concerning religious matters, and was foremost worried about defending its economical and political interests against the strengthened royal rule.

Marguerite of Angoulème and her court’s presence in Lyon in 1524, encouraged the spreading of new ideas. For Francis I’s sister, it meant mainly returning to the primitive Church and preaching the Gospel alone.

Writings would play a key role throughout the history of Protestantism. In the late 15th century workers, typographers, engravers, craftsmen came from Germany bringing their tools and their knowledge with them. In the 1530s, early texts appeared and were on the verge of orthodoxy. Fairs enabled the distribution of books published in Anvers, Basel, Strasbourg, but mainly in Geneva where Calvinist editions developed fast from 1550 on. The best-known authors published in French ranged from Lutherans to Swiss Reformers, but in limited prints compared to Catholic works. Many printers were humanists, like the German Sebastien Gryphe. He had a free spirit, interested in new ideas and after he had worked in Venice he settled down in Lyon and distributed books be they heretic or orthodox. Among ‘radical’ printers who adopted the new ideas, Pierre de Vingle can be noted, the son-in-law of Rabelais’ printer, who published Guillaume Farel as early as 1525, left Lyon as a precaution and followed Farel to Geneva and then Lausanne. Etienne Dolet (1509-1546) published Erasmus, Lefèvre d’Etaples, Olivétan, Marot, for which he was arrested several times, and later burnt at the stake.

As writings became more important, the role of book workers grew. Most of them were immigrants but could read and write. They lived in secular communities called a« Griffarins »and had their own initiation rituals. In the parishes they attended they asked for a new type of worship with a liturgy in French so the people could understand. Social conflicts were sometimes violent.

Early signs

Until 1550, the camps were not clearly divided. A small minority was determined to break with Rome, but they were mainly foreigners. Still, a majority thought that changing the Church through faith and piety was what the humanists craved for, as they were more or less familiar with Luther’s ideas.

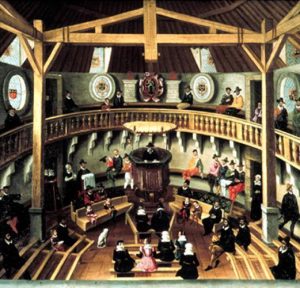

But some signs of an evolution could be seen. While the devotional Catholic trend kept developing, repression stared. Iconoclastic actions became more numerous in response, and more or less secret meetings were organised where Marot’s psalms would be sung. In June 1551 the Edict of Chateaubriant anticipated the death penalty for the heretics, and many executions followed. In 1560 the Chapter in Lyon claimed the city to be ‘a second Geneva’, and it was true that Calvin’s influence markedly increased, many pastors being appointed. Worship was no longer clandestine, and was organised in private houses or sometimes in small streets or cemeteries. A King’s envoy asked the Reformed to hold their meetings of up to several thousand people, outside city centres – the community was visible, led by pastors and a consistory, which was as good as the creation of a real Protestant Church.

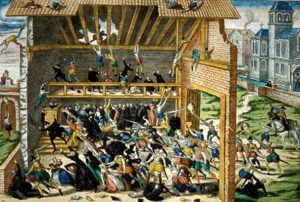

The years 1560 and 1561saw several sedition attempts as the Protestants tried to come to power, but they failed and repression escalated. Pacifying measures, under Marie de Medici’s influence caused Catholic anger, and on 1 March 1562 the Wassy massacre marked the beginning of the first war of religion.

A Protestant capital

In late April 1562, it was rumoured that a Catholic army was heading towards Lyon. In the night of 29-30 April, a group of 1,200 Protestants managed to become rulers of the city by blunt force.

The lack of reaction of the Catholic inhabitants – 2/3 of the population – is still difficult to account for: the governor of the city was absent, his assistant was probably secretly won over by the Reformation ideas ; the fear of the Baron des Adrets’s Protestant army, known for its atrocities may have also played a rôle.

The Protestants had to get organised, but they were ambivalent. They remained truthful to the King through the Guise family, but they criticised his religious policy. The Consulat with 24 elected members, half of them Protestants, was maintained, but in fact 2 new administrative bodies ruled, created after the Geneva model, firstly the Consistory, central power comprising about sixty people – pastors, ‘elders’ and people who led exemplary lives, mostly lawyers, solicitors, merchants, few peasants, few noblemen -, secondly the Council, in charge of ecclesiastical matters. Lastly, the Prince de Condé was asked to send ‘a few lords of note to conduct the affairs’, such as the Lord of Soubise in favour of the Protestants, but also the Duke of Nemours, who turned out to be an openly violent oponent, which often led to bloody conflicts.

Catholic worship was banned, religious festivals were forbidden. Reformed religious ideas were spreading, promoted by the printers and bookshop keepers’ activities. More than a hundred titles were published: combat poems, satire, pamphlets, translation of the Bible into French, prayer books, etc.

Iconoclasm burst out and was systematically organised by the Baron des Adrets’ troops who invaded the city. Many churches were looted, vandalised, even destroyed, among which the Saint-Just church and cloister, a Catholic stronghold.

Protestant rule being established, great projects were decided, such as beautifying the city, pulling down houses to widen streets, building a bridge over the Saône river. The great amounts of money spent contributed to financial difficulties that caused the city serious problems.

The ebbing

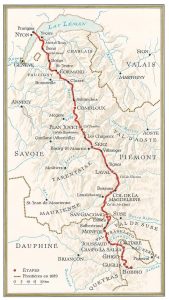

After the Prince of Condé was defeated in Dreux on 19 December 1562, Catherine de Medici ordered the Lord of Soubise to rally, in order to prevent ‘ruin and desolation’ in Lyon. The Edict of Amboise on 18 March 1563 reinstated Catholicism while awarding the Protestants freedom of worship in 2 temples. The King’s authority was restored. For almost two years Catholics and Protestants lived relatively peacefully together, the Reformed felt secure enough to organise their national Synod on 6 August 1563. Pastor Pierre Viret, President of the Consistory, was its moderator. But in later years, the Catholic religion confirmed its power. The political and administrative bodies took back control, the Consulat was modified with a Catholic majority. Churches were re-built. Interfaith conflicts, though less violent, continued, and many Protestants left the city. At the apex of the Reformation 25,000 people took part in the Holy Communion, but were only 4,000 around 1567. Pastors were expelled outside the walls, including Pierre Viret, as a foreigner.

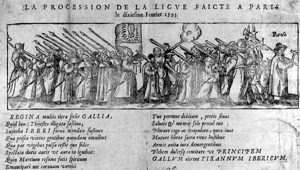

Catholic re-establishment was quick, with urban processions, worship of the Virgin, the major role of the Jesuits, who founded socially oriented religious and secular brotherhoods, all aimed at promoting the fight against the heretics.

The ‘Lyonnaise Vespers’ from 30 August to 3 September 1572, were a good example, as they echoed the Saint Bartholomew massacre in Paris on 24 August. The King, who took on the responsibility, asked that such events do not take place again in his kingdom. In Lyon, rumours and confusion led to the first violent events during the night of the 30 to 31 August. The consulat was divided but decided to save the Protestants by putting them in the city jails. In the morning of the 31st, a macabre procession organised by the militia went to the archbishopric where a sort of court of justice was set up. The Protestants who recanted were saved, the others were executed, mutilated and their bodies thrown into the Saône river. Massacres also took place in other prisons. There were an estimated 1,800 to 3,000 dead.

The harshest Catholic section had won, and the time of Protestant rule was only a vague memory. In the years that followed, intransigent Catholicism was the rule, the city joined the Ligue in March 1589, and the Protestants were expelled. In September 1595, Henri IV triumphantly entered Lyon, and the wars of religion ended in 1598. After the Edict of Nantes was published, the Protestants discretely came back, a worship place was established in the suburbs, but the confessional coexistence was fragile until the Revocation in 1685, which turned Lyon into the most Catholic major city in France.