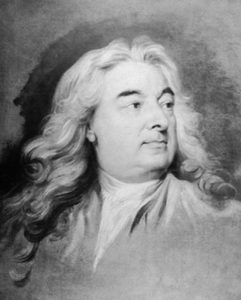

Pastoral mission (july 1765-1786)

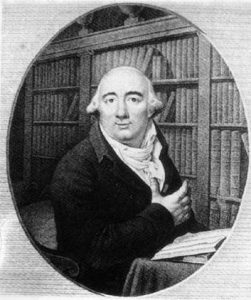

The son of a pastor, Paul Rabaut, Rabaut Saint-Etienne was born in Nîmes. He spent his childhood in the atmosphere of insecurity and anxiety that pervaded families of “Churches of the Desert” pastors.

The insecurity made Rabaut send his son to a boarding school in Lausanne to continue his education. There he studied theology.

He was ordained pastor in Lausanne on 11th November 1764 and was immediately appointed to Nîmes as his father’s assistant.

The emancipation of the Protestants (1786-1789)

Rabaut Saint-Etienne consecrated his life to an essential task, i.e. to improve the lot of his fellow worshippers. In this cause he went to Paris and contacted the Marquis de La Fayette, who was desirous of ending the exclusion of French Protestants. Thanks to La Fayette he met Malsherbes, a member of the government, also in sympathy with the Protestant cause. The work of obtaining legal status for the Protestants was supported by several influential people close to the king, Louis XVI, and they wrote pamphlets to this effect. At the end of 1786, Rabaut Saint-Etienne wrote his own pamphlet and tried to press for acceptance of the most liberal thesis possible.

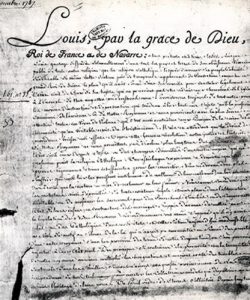

Finally, the Edict of the non-Catholics, called the Edict of Tolerance, was signed by Louis XVI on 7th November 1787. It was restricted to civil status. While regretting its limitations, Rabaut Saint-Etienne welcomed the signing of the bill and claimed : “acknowledgement does not rule out hope, but allows it.”

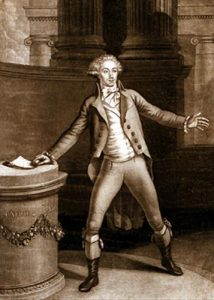

The revolutionary

Rabaut Saint-Etienne was a member of the National Assembly and of the Convention.

On 27th March 1789 he was appointed representative of the Third Estate at the Estates-General, for the Senechal’s Jurisdiction at Beaucaire ; he sat with the constitutional reformers. To his way of thinking, the National Assembly should remain faithful to its founding principles, namely equality and freedom, while maintaining the principle of monarchy.

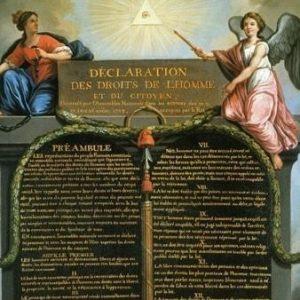

He actively took part in debates over the Declaration of Human Rights (August 1789). He also stuck to the philosophy that “freedom of thought and opinion” is “inalienable and enduring”, and that “the rights of all French people are the same”.

“Thus, Gentlemen, the Protestants do all they can for their native land ; but their native land is ungrateful ; they serve it as citizens, but they are treated as outlaws ; they serve it as men you made free, but they are treated as slaves. A French Nation exists at last, and I appeal to it on behalf of the two million loyal citizens, who today claim their rights as French. I would not be unjust enough to think the nation could utter the word intolerance ; it was banned from our language, and will only be remembered as one of those barbaric and outdated words no longer used because the concept it represents no longer exists. But, Gentlemen, this is not the same Tolerance I call for ; rather it is freedom.” This famous speech was delivered by Rabaut from the Tribune at the National Assembly, on 23rd August 1789.

(« Ainsi, Messieurs, les Protestants font tout pour la patrie ; et la Patrie les traite avec ingratitude : ils la servent en citoyens ; ils en sont traités en proscrits : ils la servent en hommes que vous avez rendu libres ; ils en sont traités en esclaves. Mais il existe enfin une Nation Française, et c’est à elle que j’en appelle, en faveur de deux millions de Citoyens utiles, qui réclament aujourd’hui leur droit de Français. Je ne lui fais pas l’injustice de penser qu’elle puisse prononcer le mot d’intolérance ; il est banni de notre langue , où il n’y subsistera que comme un de ces mots barbares et surannés dont on ne se sert plus, parce que l’idée qu’il représente est anéantie. Mais, Messieurs, ce n’est pas même la Tolérance que je réclame ; c’est la liberté ».)

Thus, thanks to the French Revolution, the Protestants were reintegrated in the national community. Freedom of thought was granted to them with the Declaration of Human Rights. Then access to all civilian and military positions came with a constitutional text on 24th December 1789, and freedom of worship on 3rd September 1791.

The execution of Rabaut Saint-Etienne

In September 1792, Rabaut Saint-Etienne was made a member of the Convention.

He sat with the Girondins who were then more moderate than the extreme tendencies supported by Robespierre or Marat.

He argued against Louis XVI’s prosecution, voting for an “appeal to the people” and a reprieve.

The clash between Girondins and Montagnards became fiercer. On 2nd June 1793, the Girondins were expelled from the Assembly, and Rabaut hid.

On 5th December 1793, Rabaut Saint-Etienne was arrested, prosecuted in the revolutionary court of justice and executed.