Early years (1787-1814)

- Nîmes and Geneva (1787-1805)

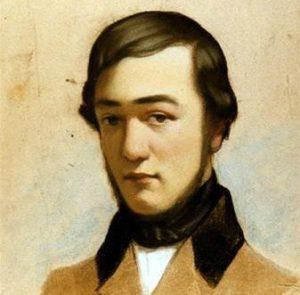

Guizot was born in Nìmes on 4 October 1787, a month before the proclamation of the Edict of Toleration that gave recognition to Protestants. He was the son of a lawyer, André Guizot, and the grandson of Jean Guizot, a pastor of the Désert, a termsymbolizing the clandestine existence of Protestants after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes.

The Guizot family welcomed the Revolution in 1789 with enthusiasm. But André Guizot sides with the Girondins, and is sentenced to death on the scaffold at the time of the Terreur His two sons, François and Jean-Jacques, aged seven and five, were taken to the prison of Nîmes to kiss their father farewell. Elizabeth Sophie Guizot, the 29-year-old widow, is left on her own and responsible for her children’s upbringing. She took them to Geneva from 1799 to 1805, to ensure them a correct education. She was a passionate, authoritarian woman, deeply religious, and had a great influence on her eldest son.

- Literary and academic beginnings (1805-1814)

In 1805 Guizot, aged 18, found himself alone in Paris to study Law, away from his mother’s influence and his home background. His mother had hoped he would come back to Nîmes and follow in his father’s footsteps, but Guizot was interested neither in reading Law, nor in returning to his home town. His life took a decisive turn when he met two persons who were to provide him with their culture and their connexions : Philippe Alfred Stapfer, a former Minister of the Helvetic (Swiss) Republic, and Jean-Baptiste Suard, member of the Academy and founder of the Publiciste.

In 1812, Guizot married Pauline de Meulan, 14 years his senior, a liberal aristocrat from the Ancien Régime. A woman of great intelligence, she earned her living by writing. In the early years of their marriage, they published together Les Annales de l’ éducation (1811-1813), thus starting a happy relationship and a lasting intellectual fellowship which ended with the death of Pauline in 1827. They had a son, François, who died in 1837, aged 21.

At the end of the same year, his increasing reputation earned him his appointment to the chair of Modern History at the Sorbonne.

The Restoration (1814-1820)

- Early steps in politics (1814-1820)

With the return of the Bourbons, Guizot gave up teaching to become a high-ranking civil servant. Too young to run for Parliament (the mandatory age was 40), he acted as unofficial political adviser to several ministers. This period saw the foundation of the Doctrinaires’ group : confronted to the ultra royalist aristocracy who dreamed of a return to the Ancien Régime, these liberals sought a new form of government suited to post-revolutionary society by a liberal enforcement of the Charter.

Guizot rapidly stood out as the movement’s leader. A Protestant with middle-class origins, he was a whole-hearted supporter of the 1789 Revolution ideals of liberty and civil rights. Like his liberal friends, he was opposed to democracy which, to his mind, was closely related to revolutionary anarchy and despotism. He wished to set up a representative government consisting of influential people capable of acting according to reason and elected by tax-paying citizens. The decisions taken by the government were to be controlled by both Chambers and widely publicized. Thus Guizot hoped that society would be ruled by reason rather than by the supremacy of the people.

- A great intellectual (1820-1830)

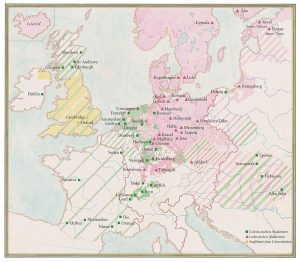

The assassination of the Duke of Berry in 1820 brought the ultra royalist party back to power. As head of the liberal opposition, Guizot was suspended from all his duties. At this time began his most prolific period of intellectual creation, as a political thinker and historian. Between 1820 and 1822, he published his most famous political work in support of a constitutional monarchy and delivered his lectures on L’Histoire du gouvernement représentatif. His lectures were suspended by the government from 1822 to 1828. He then wrote L’Histoire de la Révolution d’Angleterre which – according to him and his contemporaries – foreshadowed French history with the founding of a permanent constitutional monarchy.

As from 1828, political prospects opened up once more. Guizot resumed his lectures at the Sorbonne, cheered by his young audience crowding to attend the event. In order to publicize his opinions, he collaborated with the establishment of the Globe and he founds La Revue Française, which he heads from 1828 to 1830. In January 1830, having reached the legal age for Parliament, he is candidate for the arrondissement of Lisieux, in the département of Calvados. He will be its député for 18 years. His influence was now at its highest.

The July Monarchy (1830-1848)

The July Monarchy had established a constitutional monarchy, thus following to the ideas of Guizot. As theoretician and philosopher of the new regime, he became its essential actor. Guizot was member of the “resistance” party, as opposed to the “mouvement” party, and hoped to give time and stability to the representative monarchy and ensure its durability.

- Minister for Education (1832-1837)

After a short period as Interior Minister (1830), Guizot was appointed Minister for Education, which he remained almost continually until 1837. His law of 28 June, 1833 created the municipal primary school. Each municipality was to finance a boys’ school and a teacher. Guizot also had the intention of creating schools for girls, but his proposal did not interest the députés. He planned the establishment of an Ecole Normale in each département for the training of teachers and set up a staff of school inspectors.

As Government Minister, Guizot founded other institutions which still exist today : for the upkeep of France’s historical heritage, he founded the General Inspection of Historical Monuments, the Société de l’histoire de France and the Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques. The latter were to strengthen the links between the French and their past by the research and publishing of previously unpublished documents. Guizot likewise restored the Académie des Sciences morales et politiques, which had been closed on Napoléon’s orders.

Guizot’s second wife, Eliza, died at the age of 29, after the birth of their third child. She was the niece of Pauline de Meulan and much younger than her husband with whom she had had a most passionate relationship., Despite his government duties, Guizot the widower took remarkable care of his children. His mother, then 70, took on the upbringing of her grandchildren.

- The years of power (1840-1848)

After a brief period in the opposition, Guizot was appointed ambassador to London. A few months later, he became Minister of Foreign Affairs, replacing Thiers who had been at odds with Louis-Philippe as a result of his aggressive policy towards Britain on the Oriental question. Guizot stayed in office until 1848 ; though in an unofficial capacity prior to September 1847, he actually ran the government nominally presided over by Maréchal Soult.

Guizot’s foreign policy advocated peace. He favoured good relationships with Britain, with which France had often been at war. Nevertheless there remained numerous reasons for discord, as the two great powers were still at war in different regions of the globe. In collaboration with his British counterpart George Aberdeen, head of the Foreign Office, Guizot elaborated diplomatic solutions to these conflicts. This was the first Entente Cordiale.

On the home front, Guizot wished to strengthen the representative government by a policy of stability. It led him to immobility when faced with requests for reforms and the enlargement of the electoral system. He was violently attacked in Parliament, but Guizot was an exceptional orator listened to by the entire Paris population as he dominated his adversaries with his brilliant wit. The 1846 election was a personal success, and confirmed him in his conservative policy. He failed to foresee the evolution of opinion. In 1847 new demands for electoral reforms again met with Guizot’s opposition. Their instigators launch a “banquet for reforms” campaign in the English fashion in order to address public opinion directly. But the movement escaped its organizers. In Paris, in February 1848, the last banquet turned into a revolution, and Guizot was obliged to find refuge in England.

The years of retirement (1848-1874)

Back in France, Guizot was defeated in the 1849 elections and renounced to any come back to power, but he still remained active and influential. From now on he directed his political activities towards the uniting of the Bourbon and Orléans dynasties.

For Guizot, his was likewise a period of great intellectual activity. Lacking financial means, he was obliged to make a living with his writings. Following the publication of his Mémoires, Guizot wrote three volumes on the Christian religion entitled Méditations. At the age of 80, he began writing L’Histoire de France racontée à mes petits-enfants, (The History of France told to my grandchildren) ; after his death, it will be continued and published by his daughter Henriette. It was one of the great successes of the time.

An influential member of the Académie Française since 1836, Guizot actively collaborates in the organization of elections. His welcoming speeches to new members of the Académie were eagerly awaited by Parisian society. Even the Empress Eugénie was present when he welcomed Tocqueville’s successor Lacordaire !

Throughout all these years, Guizot played a very active role in the French Reformed Church. He acted as representative of the Church to the official authorities and succeeded in having a general synod called in 1872. In a deeply divided Protestantism, he sides with the orthodox. However, alongside both Catholic and Protestant liberals, he fought for the survival of the Christian faith in the face of progressing atheism.

Guizot spent the rest of his life in his Normandy estate, surrounded by his numerous family. He died there on 12 September 1874, at the age of 86. His intellectual influence lasted well into the Third Republic. His ideas inspired numerous politicians as well as great historians of the next generation.