A multi-confessional ecumenical organisation for evangelisation

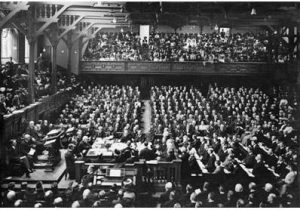

The International Missionary Council was one of the organisations that contributed to shaping the ecumenicalrequirements supported by the Edinburgh Conference, also called World Missionary Council. Its ambition was to develop a missionary cooperation between Anglican and Protestant Churches. To that end it established a Continuation Committee under the responsibility of John Mott and J.H. Oldham.

After World War I, as peace treaties redrew boundaries, including those of colonised countries, the Continuation Committee created the International Missionary Council (IMC) in 1921. Besides schooling and social actions in the field, international conferences were organised, for instance in Jerusalem in 1928, and in Tambaran (Papua New Guinea) in 1938.

The IMC was initially independent of the Life and Work and Faith and Order groups, originated during the Edinburgh Conference. It was not a member of of the World Council of Churches upon its creation in 1948. After many debates and the Conference in Achimota (Ghana) in 1958, the IMC integrated the WCC as the Commission of World Mission and Evangelism (CWME).

Within the WCME points of view started to diversify

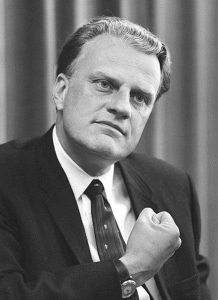

In the 1960s and 70s the WCC fought against racism, opened up to inter-religious debate, defended human rights during South American dictatorships. The WCC opted for ‘real world’ interventions in relation to the different political situations it faced (Conference in Bangkok in 1973). But this standpoint was strongly disputed by some Evangelical Protestants who attended the Commission. They felt closer to the initiatives of Billy Graham (1918-2018) linked to the stance of the United States throughout the Cold War. At the congress held by the charismatic evangelicals in Lausanne in 1974, they took a critical view of the points defended by the WCC. These views were immediately developed as the congress gave rise to a movement, called the ‘Lausanne Movement’.

In 1989 the WCC organised a conference in San Antonio. Billy Graham and the Lausanne Movement organised another one in Manilla, very openly welcoming the Charismatics and Pentecostals. The WCC feared a possible split and welcomed the Pentecostals to the Assembly in Canberra in 1991. It set up work sessions on their ‘pneumatological’ concerns, i.e. the particular emphasis placed on the power of the ‘Holy Spirit’. Jürgen Moltmann, a theologian, suggested federative thought processes.

In 1992 the CWME welcomed Catholic, Evangelical and Pentecostal representatives as fully entitled members. In 1997 the WCC adopted a joint general statement in favour of debates with non-member Churches. These reconciliations culminated at the world Christian Forum in Nairobi in 2007 attended by other ecumenical entities besides the WCC.

A confirmed opposition between the WCC and the Lausanne Movement in 2010

The differences between the WCC, its Commission of World Mission and Evangelism (CWME) and the Lausanne Mouvement did not abate. On the contrary they toughened with the hundredth anniversary of the Edinburgh conference in 2010. Some members of the CWME left in order to join the Lausanne Movement.

At the Edinburgh Conference in Edinburgh organised by the WCC, the attendees had obviously very different approaches to missionary action. Witness and conversion became prominent topics in the debates.

Shortly after the conference, the Lausanne Mouvement organised another one with the World Evangelical Alliance (WEA). The Conference in Capetown (South Africa) tried to renew the missionary partnerships between North and West, South and East.

Adopting a pragmatic standpoint Olav Fykse Tveit, the WCC’s secretary-general, hoped for a reconciliation between Geneva and Lausanne (geographically close to each other).

The WCC, though not heeded by the Lausanne Mouvement, maintained the Mission and Evangelisation division in its organisation chart. It kept reflecting on what missionary witnessing consisted of in a fragile world, afflicted by violence and often quite obscure*.

* « souvent bien obscure », cette phrase dans le texte en français sur le site n’est pas clair. Obscure, le monde? la mission, le témoignage? Donc impossible de traduire.