Commemoration of the first national synod of the Reformed Church in 1859

The French Reformed Churches appear to have ignored the jubilee of 1617. The Catholic jubilee of 1625 was similar to those of 1550 and 1600. These were all condemned by Charles Drelincourt, pastor in Charenton as ‘pagan and Judaic ceremonies involving the practice of indulgences which even the Council of Trent would have hesitated to justify ». The inspired role played by Luther as a reformer is barely mentioned on this occasion.

In France it was only in the second part of the XIXth century that the Protestants started to consider the celebration of jubilees commemorating the Reformation.

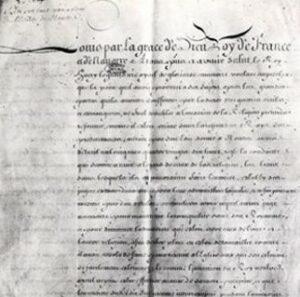

The first commemoration to involve all the French Reformed Churches took place on the 29th May 1859; this was the three hundredth jubilee of the Reformation in France and commemorated the first national synod of the Reformed Church in May 1598.In 1858 the Pastoral Conference first had the idea – they were probably influenced by the Geneva jubilee in 1836 and by other jubilees which had been held by French Reformed Churches abroad since 1850. The Jubilee commission represented different theological tendencies within Protestantism (there had already been discussion over the confession of faith). It called on every French Reformed pastor to participate and also invited Lutherans and Protestant Churches from abroad.

‘On Sunday 29th May 1859, Reformed Churches could have a special sermon dealing with the historical facts to be commemorated on the date. Suitable remarks and spiritual words of encouragement could be included in this celebration.’

Judging by the accounts describing the jubilee sent to the Society of the History of French Protestantism (SHFP) by 78 parishes, this commemoration was a great success. The biggest one took place in Nîmes and lasted for three days. It included an enormous open-air public assembly in the place where secret meetings used to take place in well-hidden spots in the countryside. (The ‘Desert’). There were sermons and discussions, alternating with songs, hymns (including choral work composed by Luther); it all brought to mind the French Reformation and those who had given up their lives for their faith in the XVIth century, at the time of the ‘Desert’. Believers were called to repentance when faith was in steady decline and to be tolerant towards their ‘Catholic brothers’ in an atmosphere of peaceful co-operation.

The first Reformation Jubilee in the French Protestant Church

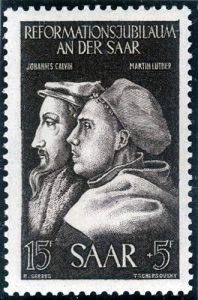

This jubilee was not to be held on a date corresponding to the actual event of the Protestant Reformation in France. In fact, in 1866, when the Committee of the Society of the History of French Protestantism (SHPF) set about celebrating the Reformation Jubilee, they did not think of commemorating it on the date of the French synod, which was considered to be too scholarly. The anniversary of when Luther posted his 95 theses was considered more suitable; (it was a rather unusual decision due to this fact and could have appeared unpatriotic to some people). However the event was considered to be a revival of the Christian conscience. For this reason All Saints Day (a national holiday in France) was chosen, but, the SHFP added, there should not be too much emphasis laid on Luther’s theses. Instead, the jubilee should be associated with memories of the French Reformation. Since then, this jubilee has been celebrated on the Sunday nearest the 1st of November.

Bicentenary of the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1885

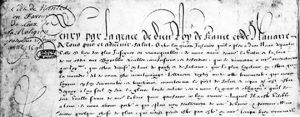

The second major commemoration of the French Reformed Church was in 1885 for the bicentenary of the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. In actual fact the committee of the SHFP was not too keen to celebrate this event publicly and they had been forced to do so by the Society of the Descendants of Huguenots Abroad.

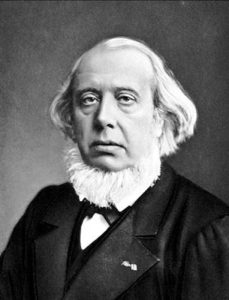

However, after the defeat of the French in 1870, there was a wave of anti-Protestantism. In spite of the need to support the Protestants abroad, it was important for the SHFP not to justify fears of ‘reviving hatred of Catholics’. This is why the SHFP, when they called on pastors to conduct commemorative services on Sunday 18th October 1885, insisted that these should reflect ‘an attitude of humiliation and national mourning’ and include ‘a fervent prayer to God that ideas of tolerance and justice may prevail’. After the various commemorative services had been celebrated on Sunday in the parishes, the SHFP held their own service on Thursday 22nd October in the evening in the Oratoire temple; there was only one foreign delegate present, from the Walloon Church. The tone was definitely patriotic, due to the sermons by Pastor Eugene Bersier (1831 – 1889) and the pastor and senator Edmond de Pressensé (1824 – 1891). There were also patriotic prayers and hymns (including one of Luther’s choral works).

In the midst of growing nationalism and anti-Protestantism, the tricentenary of the Edict of Nantes was largely passed over in silence in the spring of 1898.This first ‘edict of tolerance’ was somewhat unobtrusively commemorated in Nantes, after the general election in the large temple, which had been bedecked with the colours of the French Republic for the occasion. Once more, the pathetically small number of representatives from foreign Huguenot societies who were in contact with the SHFP and the Reformed Churches of France were not asked to speak.

400th centenary of Calvin in 1909

The French Reformed Churches had considered the possibility of celebrating a 400th jubilee of Calvin in July 1909. This was in spite of the fact that this native born Frenchman’s anniversary had been largely monopolized in Geneva, a city where the public institutions openly supported the event and whose citizens still cherished his memory. In 1909, the reformer’s jubilee was not easy to celebrate in the context of the time. It coincided with the separation of the Church and State and was ‘between the two conflicting sides of France’. The commission of the ‘jubilee of Calvin’s centenary’ was presided by the historian and pastor Paul de Félice and consisted of a majority of pastors and members of the SHFP. They decided to conduct their celebrations quite independently from Geneva; this ‘illustrious Frenchman’ should be commemorated in France. In spite of the fact that the Reformation Jubilee was chosen as the date for this ‘national’ public commemoration, it was to take place in a non-religious place, the Trocadero, and not in a temple. At the end of his speech, the Pastor Doumergue described Calvin as ‘a powerful instrument of the spirit of France and of God himself: Gesta Dei per Francos’. In a somewhat less extravagant tone, Pastor Jules.E. Roberty insisted on the role of the English Calvinist minority in the creation of the American Declaration of Rights, which had been inspired by the French Declaration of Rights in 1789.

The 400th anniversary of the Reformation in 1917 was celebrated quietly

1917 was not an ideal moment to celebrate the Reformation – indeed the war had already been going on for 3 years. In September 1917 the United States celebrated the 400th anniversary of Luther’s Reformation. However in France Frank Puaux, President of the SHFP (Society of the History of French Protestantism) did not mention the reformer when he addressed the President of the Jubilee organizational committee in America. He simply reminded him of the close brotherly ties which had always drawn together the Huguenots of France and the descendants of the Puritans who had fled to America long ago. In December 1917, in his annual address as President of the SHFP, Puaux compared President Wilson’s proclamation when the United States joined the war to Luther’s declaration in Worms. The reformer had pleaded for freedom of conscience and justice, neither of which existed at all any more in the Germany of 1917. The whole of Europe had become paralysed with fear as it struggled with the devastating evil of its opponent.

In 1917 Germany held a very patriotic jubilee of the Reformation. The reaction of the French ‘Metaphysical and Moral Review’ was to publish a special issue about the way in which the Reformation had taken place in France, England and also in Germany. This did not appear, however, until 1918.

There were many celebrations at the end of the XXth century

After the seventies there was great enthusiasm in Europe and especially in France for the commemoration of past historical events. This was because the traditional social structures and institutions that had always transmitted the memory of past events were rapidly disappearing one by one. So France decided to begin celebrating the Reformation jubilees once again.

In France, the commemoration of the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1985 was not easy to celebrate, either for the SHFP or for the Reformed Church of France. If there was too much Protestant hagiography, this could lead to trouble with the Catholics and the ecumenical movement. For this reason a strictly non-religious viewpoint of history was put forward in all colloquies and events organized by the French Protestant Church.

This commemoration of 1985 was a success; there was a celebration in Unesco presided over by the President François Mitterand and many foreign delegations. In fact it set in motion a cycle of Protestant commemorations:

- 1987 (200th anniversary of the Edict of Tolerance,

- 1989 (200th anniversary of the French Revolution),

- 1998 (400th anniversary of the Edict of Nantes) – this was less provocative because many people believed that tolerance was of supreme importance.

The jubilee of 2000 was largely monopolized by the Roman Catholics so the Protestants did not want to attract too much attention. Incredibly, when Pope John Paul II introduced the ‘Holy Year’ in Rome, it was only the Protestants who appeared to be shocked by the sale of ‘indulgences’, a practice which had been going on within the Catholic Church for the last seven centuries. So the past misunderstandings between the two faiths were still very much present in the year 2000.

In 2009, the 150th anniversary of Calvin’s birth gave rise to many commemorative events, especially in Noyon, Calvin’s birthplace which has a Calvin museum. In the course of the year many articles and books about him were published and his works were included in the prestigious ‘la Pléiade’ collection.