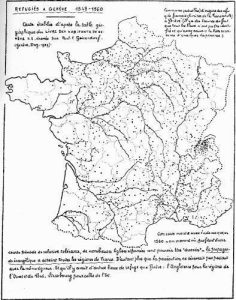

Switzerland at the end of the 17th century

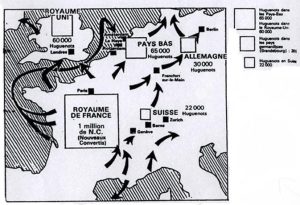

The Confederation then comprised thirteen provinces, allied states and subject states, united under the federal Diet. The Bern and Zurich cantons were the most important. The religious conflict divided the country in two blocks. Protestant Switzerland comprised the Republic of Geneva, the evangelical cantons controlled by Bern and the Neuchâtel county. The refugees’ arrival only worsened the inter-confessional tension and potentially endangered the neutrality of the country while deteriorating the fragile economic situation. Pauperism was dreaded because of the increasing number of tramps and the financial burden they represented to the municipalities, who were obliged to provide aid to the poor. Thus this temporary type of hospitality given to the refugees induced them to leave, mostly to Germany.

Two waves of refugees

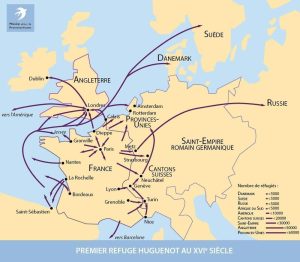

The first wave took place between 1540 and 1590 and mainly concerned Geneva.

During the second wave, before and after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, refugees came mostly from the Dauphin, Cévennes and Languedoc regions; the major route of exodus was the passage from Lake Geneva to the Rhine River. The roads to Geneva and the Valais region led to Lausanne, which was densely populated and became one of the centres of attraction for the Refuge.

Hospitality of the cantons and the difficulties

The massive influx of refugees in the Vaud canton, required that the local authorities and the inhabitants participate in meeting the immediate needs of the displaced persons.

Lodging was ensured by “public housing”, hostels (expenses paid for by the authorities( and hospitals, but also inhabitants who volunteered (refusals were rare) or were obliged to in case of massive influx. Transportation for the weakest ones was by boat or on wagons, and the transporters were generally paid. The extensive network of hospitals in the Vaud canton was opened to the refugees: lodging, food, health care, “passa ”, i.e. alms given by a pastor, enabling the recipient to “pass” further to the next locality where the refugee could ask for another passage. This effort can be explained by the wish to hasten the conveyance of refugees from one stop-over to the next, and thus shorten their stay in localities.

Reformed Switzerland consisted of a transit route from a few weeks to a few months, for most refugees who were either waiting for relatives or help, or information, who did not want to get too far away from France in case Protestantism was restored. The refugees were mobile, often changed houses, were often poor, and the authorities had trouble curbing the roaming tramps and beggars.

A minority only settled permanently, notably those who could set up an economic activity, especially a factory. The authorities then awarded them a special status as “resident” without political rights, but established some agreement with the city, and they were registered in a special book. Only those who declared in writing that they came for religious reasons were accepted. Very few acceded to bourgeoisie.

Reception facilities

The massive influx of Huguenots caused numerous problems. In the beginning it was orderless, evangelical cantons complained of unexpected arrivals. Seeing how poor those people were, Bern realised that all Protestant States should co-operate, and declared early its inability to receive all the emigrants in its territory. In 1684 the “Reformed Conference”, first limited to Bern, chose to create a common fund of 30,000 florins to which each State would contribute; one fifth of Bern’s income was spent on helping refugees in 1691. The cantons, despite some practical problems did not question the principle of financial solidarity, but verified that help was granted only to “servants of the faith”. Indeed in those days pauperism produced every kind of fraud and the authorities acknowledged that “a great number of people might leave their homeland rather to avoid poverty than not to be persecuted.”

The Bern authorities created new administrative structures. The most important was the Chamber of Refugees set up in 1683 whose range progressively spread to the whole territory. It acted as a regulator for all the questions raised by the Refuge. It was supervised by the government, and remained in force until 1789. Its main activity was to organise fund-raising events and to manage these charitable funds.

A “Salt Commission” acted as a deposit bank for the collected funds, and managed the money the Swiss evangelical churches consented to allocate in order to assist the refugees. Moreover it organised refugee evacuation, and helped them define the routes to be followed.

A Chamber of Commerce to protect and develop local industry, contact French Refugees, and check the qualifications and entrepreneurs’ abilities as well as to promote new manufacturing techniques. It also suggested a perpetual right of residence to established manufacturers.

Besides Swiss help, the refugees helped one another and created French Allowances, the largest one was granted by Lausanne. The Allowances were not limited to material help, but also led to diplomatic activities, such as petitions to the French king, contacts with Protestant princes, or to organise social life, moral supervision, relations with the local people. They even promoted the project for emigration to Ireland, that failed.

Overall aid to the refugees was based on charitable funds raised by the Evangelical cantons, strictly managed in Bern, as well as on local institutions in the cities and on the inhabitants. The participation of everyone, ordered by Bern and accepted, enabled to compensate for structural and financial deficiencies. The effort was huge.

A difficult integration

To prevent worsening the relations with Catholic cantons, the Protestant ones received the Huguenots, helped them, but only as passing guests. All the more as the political and economical situations, with scarcity of wheat, became strained. In spite of the common religion, the archives unveil jealousy, xenophobia, the “worthless mouth to feed” the professional competitor; even the Swiss pastoral circles were afraid of the competition with French pastors! In 1687 Lausanne was full of refugees and asked the Bern authorities to direct them to other passages, in spite of the risks.

In 1694 Bern ordered all refugees to leave the territory, and sent them to German states, to the Netherlands or to England. The effect of this decision was minimised after the English envoy to Switzerland obtained that, by “sorting”, some were allowed to stay and be naturalised. The main cities kept half of the refugees. In 1698 the situation had not evolved, so Bern made the decision to coordinate the departure orders all over the territory; cities were asked to contribute to expel the refugees, and thus definitely solve the problem. New host countries had to face the flow of this population, mostly poor people. Brandenburg protested and did not want to become the ”Swiss hospital”. In January 1699 Bern promulgated a new mandate forcing all refugees to be ready to leave. A month later Bern changed its mind whereby cities had to make two lists of refugees, namely those who had to go and those they wanted to keep with a view to naturalisation. Despite the middle-class being opposed to the refugees, circumstances were progressively clarified, and at the turn of the 18th century theoretically the naturalised alone remained and had the same rights as the native Swiss.

At first the pastors were welcome, but finding a parish for them would become a problem. In 1683 the Academy in Lausanne only deemed “exceptional souls” worthy of being appointed pastoral office, and only after passing an exam on biblical texts. As for the “ordinary” ones, the Academy said they “should try their luck elsewhere or differently”.

Concerning the doctrine, pastors were asked to sign a proclamation of faith of Calvinist orthodoxy, opposed to the liberalism taught at the Saumur that academy many had attended. The Lausanne Seminary, founded by Antoine Court in 1729 provided theological training to those who covertly went to France. Antoine Court had the Desert Churches accepted. At the 1744 synod he took over Benjamin du Plan’s charge as representative of Desert Churches to European countries.

Contribution of the Refuge to Switzerland

At the end of the 17th century the economic situation in Switzerland was especially bad with the wheat crisis, impoverishment and unemployment.

Protestant historiography has always insisted on the positive contribution of the massive influx of a reliable population with a solid moral education, with unknown techniques, and a willingness to reward the generous host country by its work. The quality of the French material civilisation at the end of the 17th century granted exiled craftsmen favourable circumstances as they generated an economic boost in host countries.

Modern historians tend to modify this view. The economic contribution of the first Refuge (1551-1600) to Geneva, Zurich and Basel is uncontested thanks to the setting-up of factories , especially textile in Lausanne, as well as goldsmith and clock-making. It also reduced unemployment and poverty. But during the second Refuge, in a city like Bern protectionist policies were slowly relinquished, French businessmen were confronted with a lack of capital, an under qualified workforce, and the inflexibilities of the Old Regime. The notion of confessional solidarity helped promote the economy slowly, justified obtaining the right of residency and of bourgeoisie for the refugees. The city co-signed the loans to entrepreneurs, granted tax exemption or market protection. The State signed agreements with businessmen directly. Implanting a factory authorised exclusive production, for instance the lace trade in Lausanne.

Most refugees only passed through, and all trades were present in the different places, there were traders, peddlers, clothes makers, food suppliers, builders, even famers, but mostly bakers, whose activity was strictly watched and financial help cut, because of the wheat crisis at the end of the 17th century.

Some practiced liberal professions over longer periods of time, such as teachers or surgeons.

A few numbers

It is difficult to quantify the number of refugees who passed through Switzerland as archives are often fragmentary.

A considerable number left France through Switzerland: 140,000 to 160,000 from 1680 to 1690.

An estimated 22,000 settled in the French-speaking cantons mostly for language reasons, though French-speaking parishes were established in Zurich, Shaffhausen, Bern and Basel. Cities in the Canton of Vaud lastingly sheltered large Huguenot colonies. In 1689 Lausanne had 6,204 inhabitants of which 20%, that is 1,598, were refugees. The passage had to be negotiated with German princes and free cities, and also with sovereigns in Scandinavia and the United Provinces, to guide the influx of refugees willing to respond to the requests of German princes, notably the Elector of Brandenburg.

Most historians reckon that the Confederation sheltered at least 60,000 refugees, and that about 20,000 settled there. Between 1680 and 1689, 30,000 refugees were hosted in Geneva, with a maximum influx of 12,000 in August and September of 1687; about 45,000 had passed through Switzerland by the end of the century. Moreover, in 1689 the “devastation” of the Palatinate by the armies of Louis XIV took place, and refugees already settled there came to Switzerland for shelter.

In the late 17th century, the number of arrivals depended on the political situation. After joining the league of Augsburg the Duke of Savoy re-established reformed worship and encouraged the French to settle in the Piedmont valleys. But in 1698, the Duke chased about 2,000 refugees away, implementing an exclusion agreement with Louis XIV.

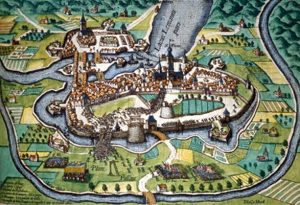

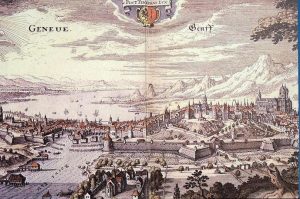

The case of Geneva, the “Protestant Rome”

The situation of Geneva was special. The Reformation was adopted by the General Council as early as 21 May, 1615. When Calvin settled there, his organisation of religious or political structures conferred exceptional influence to the city.

- The first wave

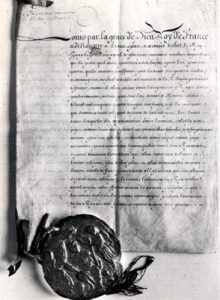

Following the first persecutions, Geneva attracted a large flow of French refugees. It thus became the undisputed capital of French-speaking Protestantism. The authorities of the city opened a special Book and granted a specific status to the newcomers. For instance the “inhabitant” was neither a passing foreigner, nor a bourgeois who had obtained or bought his title; he had no political rights and his children were called “natives” but not “citizens” of Geneva. But a sort of agreement linked the refugee to the city he had chosen, and his name was recorded in a special Book. He was accepted only if he declared in writing that he settled “only because of his desire to live according to the holy evangelical religion genuinely announced there”. The Book of inhabitants was opened in 1549 comprised 4,800 names until 1560 when it was closed because of a political attempt to coexist with France. It was re-opened after the Saint Bartholomew with 20 arrivals per day. Later, the Edict of Nantes stopped this exile, but a memory of places and links remained and would be revived if necessary.

While many refugees only passed through Geneva, some settled and acquired either habitation or bourgeoisie, generally the wealthiest and most “useful” to the economy. Such was the case of Robert Estienne, a printer.

Geneva evolved from a little town to a renowned cultural and economical centre. Genevese publishing in the 16th century was a French business. Clock-making and goldsmithing as well as the textile industry gathered momentum. The city had doubled its population over a period of ten years with 5,000 refugees. But 3,000 refugees went back to France after the edict of Nantes was promulgated.

The “French Allowance” was instituted by David de Busanton in 1545 to help refugees. Its wealth increased during the 16th century and the first half of the 17th century thanks to numerous private gifts. During the year 1687 the Allowance distributed about 10,000 florins.

- The second wave (1660-1720)

It started before the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes.

The status of Geneva, a free city, allied to evangelical cantons, but surrounded by lands belonging to the Duke of Savoy and of the King of France, was quite perilous. Louis XIV put Geneva under French surveillance, from 1679 the guardianship was represented by the French resident, who interceded with the city’s authorities to obtain the eviction of Huguenots.

Up to 350 people per day passed through Geneva in the year 1687. During the decade from 1680 to 1689 Geneva helped about 30,000 refugees. Besides the previously mentioned industrial activities, specialised activities developed consisting in re-editing the texts of pastors of the former century. Peddlers left from there to smuggle New Testaments, religious treatises or Reformed texts into French.