Very quickly, the Protestant world encouraged the development of a demanding technical education that took its place next to the teaching of philosophy, the humanities and theology.

In the 16th century, education was one of the priorities of Humanists and Reformers (Luther, Melanchthon, Calvin, Bucer, Rabelais, Montaigne). Luther entrusted this responsibility to families and to the civil authorities. Melanchthon, like other Humanists, wrote educational treatises and instruction manuals.

In Strasbourg, the reformer Martin Bucer created an establishment where the Humanities were taught. This was the first “secondary school” or high school. As soon as it subscribed to the Reform, the city of Geneva created a college.

In France, reading and writing spread quickly in reformed circles. “The Reform was passionate about educating the people. It wanted every man to know how to read, and which book? The one from which it drew life (Jean Jaurès, 1911).”

After the Edict of Nantes was signed, Protestants were authorized to maintain schools in the cities where the reformed church was recognized. Great attention was given to religious instruction. Theology, philosophy, the humanities and law were taught in the Academies. Those of Saumur and Montauban were famous.

All these establishments were closed after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes.

-

Philipp Melanchthon (1497-1560)

-

Martin Bucer (1491-1551)

-

Johannes Sturm (1507-1589)

-

The Protestant education

in the 16th century -

Protestant education

in the 17th century -

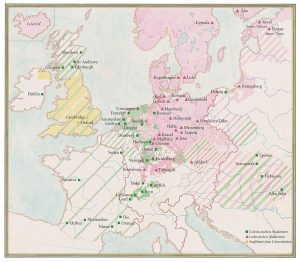

The Reformed Academies in the XVIth and XVIIth centuries

-

Pierre Bayle (1647-1706)

-

Blaise Pascal (1623-1662)

-

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778)