Protestants, including legitimists, were advocates of liberty of conscience

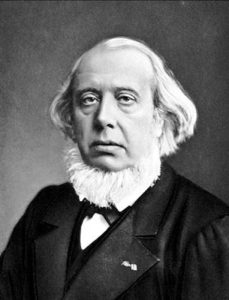

Like the great majority of the French, Protestants were tired of the Emperor’s ceaseless wars, and in spite of bad memories left by the Ancient Régime, they welcomed without great fear the return of Bourbon on the throne of France. They thought the egalitarian legislation of the French Revolution and the evolution of mentalities would protect them from new persecutions or even mere discrimination. Louis XVIII well remembered being on good terms with Protestant personalities during his long exile, and a Protestant, Arnail François de Jaucourt was one of the five members of the provisional government formed after Paris had capitulated. Two Reformed Protestants, Boissy d’Anglas and Antoine Chabaud-Latour partook in the drawing up of the Constitutional Charter, which guaranteed liberty of conscience and ensured the salary of the ministers of recognized religions. At that time, the young Guizot was appointed secretary-general to the Ministry of the Interior.

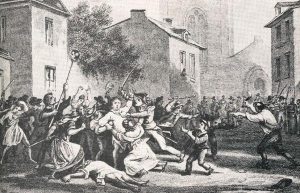

But after the Cent Jours, Protestant mistrust of the Bourbons was brought about by the White Terror of 1815 which had resulted in the massacre of numerous Huguenots in the Protestant areas of the Gard département.

The White Terror

The name White Terror had been given to local, counter-revolutionary movements organized in 1795 to avenge the Monarchy overthrown by the Revolution (and the red terror). The rebels committed violent massacres among those whom they accused of favouring the Republic.

The name White Terror was likewise given to a counter-revolutionary and ultra-royalist movement that threatened all those whose previous political sympathies had made them suspect of attempting to oppose the Restoration after the second return of Louis XVIII. The alleged enemies were obviously the Bonapartists (by fear of a recurrence of the “Cent Jours”), but also the republicans and, in the long run, Protestants (who were obviously little inclined to support a regime granting pre-eminence by right to Catholics). As partisans not of a constitutional monarchy but of a fully restored monarchy of absolute power, they began by spontaneously organizing themselves here and there into armed gangs (mainly in the South of France) carrying out acts of terror such as summary executions, destruction of Protestant churches and violent intimidations.

The elections of August 1815 were a success for the ultra-royalist députés (Les Ultras) who won 350 of the 400 seats in the Chambre des Députés (as from then the latter was referred to as “introuvable” – non-founded, non-existent). This victory gave self-proclaimed legality to intensified violence : accounts were settled, apparently with complete impunity (particularly purges in the civil service and the army). As the political tensions rose, all those who were likely targets feared the worst. Protestants even feared the possibility of another Saint-Barthélemy massacre. But after the assassination of several marshals of the Empire (including Ney, even though a Peer of France), and when proposed laws were to give outrageous privileges to the Roman Catholic Church, Louis XVIII, who was of a rather realistic nature, dissolved the Chambre Introuvable and thus put an end to such doings. However, incidents could not be avoided, at least not until 1820. It was in Nîmes as well as in several villages of the Cévennes region and in Ariège, that Protestants felt most cruelly this re-awakening of antagonisms rooted in a long story of persecutions.

Back to normalcy

Between rumour and reality, it was difficult to assess the number of the victims of the White Terror. The fact remains that, as a result, the entire Protestant community felt a definite mistrust for the restored Monarchy.

All this was to strongly contribute to the idea that Protestants are « left wingers ». Guizot, a civil servant discharged in 1820 and whose lectures at the Sorbonne were suspended between 1822 and 1828, became an active member of the opposition. Most Protestants, even though they may not have taken part in the Revolution of 1830, were pleased to see the end of the regime established by Charles X.