Luther's ideas come to Alsace

Originally the centre of the Holy Roman Germanic Empire, the region known as Alsace today was influenced from 1520 onwards by the early writings of the Reformer Martin Luther. With very few exceptions, Strasbourg publishers agreed to diffuse new ideas by publishing reformers’ tracts and numerous pamphlets. This allowed the propagation of evangelical theses given to a large, enthusiastic congregation by such well-known preachers as Matthieu Zell, an officiating priest at the cathedral. Well-known and very active theologians and exegetes such as Wolfgang Capiton, Caspar Hédion and Martin Bucer, strengthened and built up the reformation movement amongst craftsmen and the moderately well to do of the town. In 1524, Saint Aurélie, the market gardeners’ parish, asked Martin Bucer to be its pastor and preacher. Even though most members of the Great Chapter, the chapters of Saint Pierre le Vieux and Saint Pierre le Jeune, as well as a large number of the traditional clergy, refused to accept the ideas of the Reformation, the bishop of Strasbourg, Guillaume de Honstein, in spite of his opposition, was unable to curb the demand for change.

In Strasbourg, the new Protestant Church was governed by the municipality

In 1523 – 1525, the first upheavals took place ; the municipal government of Strasbourg, the “Magistrat”, participated largely in responsibilities that were traditionally attributed to the Church ; it passed laws on preaching, granted the Church the right to induct pastors in the seven parishes of the town and took the responsibility, normally attributed to deacons, of providing for the poorer members of the community.

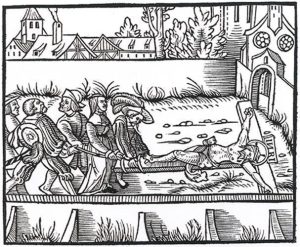

A revolt which was repressed in bloodshed

During these years, some of the rural communities of Alsace that had adhered to the Reformation, took up the claims of the “laced shoe” (Bundschuh) movement : the “Twelve Articles”, written by Swabian peasants, caught the imagination of a great number of people in the countryside in Basse Alsace – they fought for the right to elect their pastors or remove them from office. But the duke of Lorraine savagely repressed the movement and thousands of people were killed in the town of Saverne.

The celebration of mass was abolished in Strasbourg

As from 1525, the Reformation gradually spread throughout the territorial Churches governed by the local prince or the Magistrate. From 1526 to 1547, the Reformation made great progress in Strasbourg. In 1529, the Magistrate, supported by a large part of the population, voted that mass should be abolished ; violent iconoclasm spread – notably among craftsmen – to the detriment of devotional images. However, after further reflexion, some liturgical aspects of an iconographic nature as well as other traditions related to Church life were reintroduced (such as the Christmas Day holiday).

A Protestant Church observing a "middle of the way" theology

Whereas Luther’s followers presented the Augsburg Confession as representative of their convictions, it was at the diet of Augsburg in 1530 that the people of Strasbourg adopted a point of view midway between Zwingli’s symbolism and the Lutheran conception of Holy Communion – this middle of the way theology was expressed in a confession of faith shared by three other towns and called the Tetrapolitan Confession. This midway position adopted by the Strasbourg reformers, was of a moderate and diaconal nature, and quite characteristic of the Reformation in the Rhine country – it insisted on the importance of the study of the bible and inner piety, as expressed in the decree of 1534. The disciplinary aspect of church life was not too strict : small, local, religious groups of a confessing nature and taking their inspiration from the early Church, were tolerated in evangelical parishes until the Magistrate, for fear of dissent, put an end to them. The Strasbourg Church built up its liturgical, doctrinal and ecclesiastical structures ; the Church authorities instituted a twice-monthly meeting of pastors and three representatives of the Magistrate (Kirchenpfleger), in order to deal with all matters concerning the ministry and doctrine.

The growing influence of Strasbourg Protestantism

The training of protestant pastors made it possible to develop a catechism and improve the quality of instruction given to future pastors. In 1538 a Great School was opened (now the Gymnase or lycee Jean Sturm. It was run by the humanist Jean Sturm and trained future executives for Basse Alsace. Strasbourg Protestantism was influential : Martin Bucer wrote the Ecclesiastical Decree of Hesse in 1539 and that of the Electorate of Cologne. Its liturgy inspired the authors of the Book of Common Prayer of the Church of England. The town was well-known for its hospitality and reserved a special welcome to Huguenot refugees ; Jean Calvin stayed there from 1538 to 1541 and his Ecclesial Decrees of Geneva owes much to Bucer’s ecclesiology.

Radicals were welcomed in Strasbourg, but were later driven away

Since the peasants’ revolt had failed in 1525, radical evangelical groups began to develop and the town became a centre for Anabaptists, who were initially tolerated by Bucer and Capiton, but only until 1532. From 1534 onwards, a more repressive policy drove away members of this movement, which had been very popular amongst craftsmen and had taken root mostly in the rural Munster valley.

Churches governed by the princes and magistrates

In spite of the imperial Interim in 1548 demanding a return to catholic tradition throughout the empire, Alsace managed to maintain most of its evangelical privileges ; in the second part of the 16th century, the Treaty of Augsburg (1555) confirmed Episcopal rights granted to the princes and town magistrates. The latter were responsible for the spiritual and temporal well-being of the region’s subjects, for the naming of pastors, visits and special ecclesial legislation ; they also had the right to impose their faith.

Lutheranism

At the end of the 16th century, under the guidance of Jean Marbach, Alsace adopted relatively orthodox Lutheran ideas – contained in the Formulas of Concord in 1577.