1802-1833 : the first initiatives

Throughout a first period, from 1802 to 1833, initiatives of evangelization were taken as part of the Revival movement, particularly under the impulse of Geneva (role played by Robert Haldane). The new freedom enjoyed by the French Protestants was precarious and relative and it took time for boldness to reappear after the hardships endured as a result of the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1865).

While Methodists ventured into Protestant territory and Baptists into Catholic territory, the first evangelization organisations attracted notice by their initiatives. The foreign organizations were the first to develop an active evangelization. The British and Foreign Bible Society, the Continental Society sent pastors and evangelists. Ami Bost, from Geneva, toured Alsace from 1819 to 1822 while his colleague, Henry Pitt (1796-1835), at the same period, toured the North, from where he stirred up Baptism in France, then in the Beauce area and finally in Bayonne. Felix Neff (1797-1829), likewise from Geneva, became the “Apostle of the Upper Alps”. The French organizations, following the British, Dutch or Swiss examples, also began to be active. The oldest one, the Protestant Bible Society – founded in 1818 and taken over in1822 by the Society for Religious Studies – set itself the goal of spreading the Holy Scriptures. It largely contributed to make Biblical literature available in the towns and throughout the country.

1833-1870 : gaining momentum

These years correspond to the second stage of Protestant evangelization. The latter gained momentum in pace and scale despite the difficult general context. It was the time when the ideas that had been behind the Revival Movement around 1830, though a minority at the time, now took the upper hand over liberalism inherited from the Age of Enlightenment, and this even within the Reformed Church under Concordat rule. The creation of the French Evangelical Society, the “first to evangelize under French leadership” (la première société d’évangélisation à direction française) (Jean Baubérot), is a significant sign of this change. This important organization was meant to take over the work that had until then been done by foreign organizations. It gathered Protestants of various denominations, including foreign ones, and made its ambitions clear to the Reformed Churches : evangelization must get the support of the established Church ; if not, evangelization would be carried on without its consent. It was very active and contributed, by means of its peddlers, evangelists and pastors, to create new Protestant assemblies in areas that until then had been exclusively Catholic. Lamenais wrote : “Protestantism grabbed the flanks of Catholicism in order to eat it up” (Le protestantisme s’est attaché aux flancs du catholicisme pour le dévorer). This image, though wildly exaggerated, showed how frightened the Catholics were, since they had long forgotten that an alternative to their Church could be offered to the entire French community. From 1843 to 1847, Napoleon Roussel (1805-1878) created as many as a dozen new Protestant churches and schools in Charente. The Revivalists, who did not comply with the Concordat rule and belonged to the French Evangelical Society, spread into Catholic areas and raised concern among the bishops, much more so than the Concordat Protestants who, with the “French Central Protestant Society”, were not so concerned with evangelizing the Catholics. In that respect, though on a larger scale, they followed the example of the Baptists, who likewise wished to evangelize the whole of France, including areas that were Catholic strongholds.

This evangelization movement also had consequences on clerical life. The new assemblies willingly adopted a model of the “teaching” type, separated from the State. Throughout the second Napoleonic Empire, resistance became more obvious, above all in the 1850s. Pastors and Evangelists were arrested and sometimes imprisoned, protestant churches were occasionally closed, thus weakening the evangelization impulse. Repression, particularly harsh between1852 and1860, eased with the liberal Empire.

1870-1905 : a period of unprecedented freedom for the Evangelists

Thethird period, from 1870 to 1905 – with the signing of the act of separation of Church and State – was characterized by a dramatic change of context. From that time on, during the stable Third Republic, evangelisation was widely tolerated and accepted as never before within society. This last third of the nineteenth century (mainly as from the years 1876-77 that marked the end of the “Moral Order”) was the first period of true stable and unrestricted religious freedom for the French Protestants, against a backdrop of defeat and questioning. The general atmosphere was one of confusion : France had been crushed and had lost two provinces (Alsace and Moselle). Protestant circles, at home and abroad, expressed a desire to start all over again and to spread the Gospel with greater zeal. Such an attitude was considered as being the best cure for all ills, and a variety of large-scale initiatives were undertaken. This period was characterized by all sorts of projects, which kept alive the hope that France would altogether turn to Protestantism. A lot of Revivalists kept repeating : “Now that we are free at last, shouldn’t the Protestant Christians resume and achieve the work begun in the sixteenth century but which has petered out. Shouldn’t the Protestant Christian faith be victorious ?”

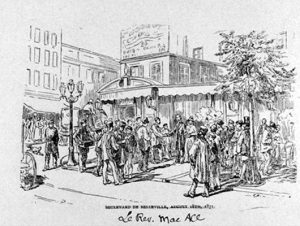

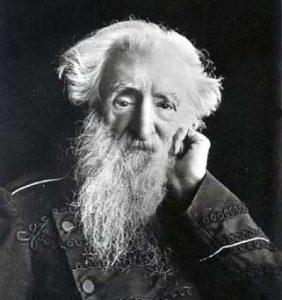

One of the most remarkable initiatives was the Mac All mission, named after the Reverend Mac All (1821-1893) who came to Paris after the defeat with the conviction that there was a real need of evangelization. In January 1872, the meeting room is opened in Belleville. Soon the Mac All mission developed with growing worldwide Protestant support. It was named “Mission for Paris workers” in 1872 and, in 1879 “The Popular Evangelical Mission”. Alongside the Mac All mission, Protestant evangelisation spread through various initiatives such as the “Parisian Committee of Domestic Mission” created towards the end of the 1870s by Eugène Réveillaud (1851-1935). He launched massive campaigns of evangelization and sensitization to Protestantism throughout France. These campaigns were characterised by a strong republican and anticlerical perspective. The implantation of the Salvation Army met the same demands for a forceful evangelization in connection with social issues. The first officers arrived in France in 1881, three years after the foundation of the movement by William Booth (1829-1912), an English Methodist pastor. “First met by the sarcasm of the jeering crowd and the suspicion of the Church” (S.Mours), the Salvation Army officers finally managed to be accepted and settled in Paris and the provinces, combining social work and evangelization (with to the magic formula “soup, soap, salvation”). Alphonse Daudet, in the periodical L’Evangeliste (1883) had severely criticized such evangelization as being inspired by purely Anglo-Saxon ideas (as opposed to the French-based Huguenot views) ; yet, thanks to different organizations for evangelism, it lasted for over fifty years until the end of the century.

Great expectations (1905-1914)

The period between 1905 and the First World War saw the last stage of the nineteenth century Protestant evangelization. Even though this was the twentieth century, the logics that were implemented and that bloomed at the time…but also died out, had been thought out in the previous century. It is no wonder that 1914 really marks the end of the nineteenth century. The Great War marked the end of an era and, at its own level, the history of evangelisation acknowledges this. Prior to 1914 the dream of a Protestant France-to-be had become truer than ever before. The separation of Church and State meant the end of the privileges given to the Church but it gave the Protestants, and particularly to those who advocated a Free Church, a considerable boost. On the other hand, the Catholic Church, distrustful of the Republic and its secular regime, looked like the remnant of an old world doomed to disappear. Could the people gather around a modern version of Christianity that would accommodate Revelation and individual conscience and allow people to be both Christians and citizens of the Republic ? Should the Reformed Church complete its work of evangelization, such dreams seemed to be within reach.

That is why this period, though of short duration, should be singled out as a period of great hope for the Evangelization Movement. The aims of such dynamics, materialised through some significant moves, were to bring the Protestants together. An unprecedented effort of coordination was made, particularly by the creation of a Federation of Evangelical Action and an important forum for evangelization, held in Paris in 1913. It gathered all the Protestant Evangelical organizations, at a time when collective conversions were dwindling and when more and more people were leaving the country to fill up the cities, thus gradually altering the traditional demographic balance in favour of the cities. Another stage of this unification process was the merging of the two main French evangelical organizations, the Central Society and the Evangelical Society, into the Central Evangelical Society. The aim was obvious : the improved efficiency of an organization fully dedicated to “evangelization per se, preaching to incredulous, superstitious or free thinking people that did not know anything about the Gospel” (Paul Barde). Total religious freedom was propitious to the use of modern methods and means of evangelization (transportable meeting rooms, tents, and missionary boats, such as the Mac All mission used). The Revival Movement in Wales (1904-1906) stirred up evangelical keenness. A meeting of the Welsh Revival in the packed hall of the “Union Chrétienne des Jeunes Gens” (YMCA), in Trévise Street, Paris, was the beginning of weekly prayers for a French Revival that were to continue until the First World War. In May-June 1914, a field-tent evangelization mission was led by Ruben Saillens (1855-1952) in Nîmes ; highly successful, it lasted six weeks and conversions were so numerous that it became impossible welcome everybody…But the Great War put an end to all these initiatives. The dream of a “Protestant France” disappeared in the nightmare of the trenches…The twentieth century had begun.