The XVIIth century : the founding and development of the Pietist movement

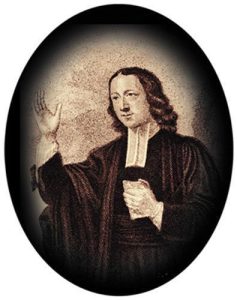

The founder of the Pietist movement was the Lutheran pastor Philip Jakob Spener (1635-1705), who was born in Alsace. When he was a pastor in Frankfurt, he gathered together his parishioners in collegia pietatis for Bible reading, prayer and the discussion of the Sunday sermon. These meetings were attended by an increasing number of participants, but they had not received official authorisation and aroused the suspicion of the authorities. Such meetings, referred to as “conventicules” were the very basis of the Pietist movement. They aimed at a spiritual maturity that could be achieved through Bible reading, the priesthood of all believers and the charitable admonishment of fellow members. Spener thought that personal religious experience was more important than adherence to a confession of faith. He insisted on the importance of “conversion” – the believer had to go through a crisis of despair followed by the experience the gift of God’s grace. He was expected to bear public witness to this experience : emotions were an important element of Pietism.

The orthodox Lutheran Church soon came to criticize the Pietists and sometimes even persecuted them. Spener quarrelled with the Elector of Saxony, but the Hohenzollern family showed more understanding and in 1691 Spener became a pastor in Berlin. Auguste-Hermann Franke (1663-1727), professor at the university of Halle, drew up a set of rules for the movement, founded several charitable institutions (schools, orphanages, colleges for poor students, popular editions of the Bible). As a result, the Pietist movement spread far and wide, even setting up the first missions in Asia.

The XVIIIth century : a new development in the Pietist movement

A new dimension was added to the Pietist movement by the Saxon nobleman count Nicolas von Zinzendorf (1700-1727). He provided refuge for a group of United Brethren ; they were descendants of Jan Hus’ disciples and had been chased from their homes by the Hapsburg persecution. Zinzendorf settled them on his estate and gave the name Herrnhut (The Lord’s watch) to the new community which was known all over Europe as the « Moravian Brethren ». They were divided into « bands », practising different spiritual exercises according to their level of spiritual experience. Moravian piety was joyful, romantic, emotional, a religion « straight from the heart » ; for them, Christ’s sacrifice in atonement for our sins was of the greatest importance – they even celebrated Christ’s blood and wounds, a practice which some people considered to be morbid. After some yeas of uncertainty, the Moravians established their own theology of an orthodox nature and acceptable to all branches of Protestantism. New communities sprang up all over Europe and America and their missionary activities became widespread.

At the end of the XVIIIth century, German Pietisms stressed the importance of fulfilling one’s duty to society and of education in particular, which led to a new economic status quo. The Moravian Brethren were scattered far and wide, which was an important factor in their development. As J.F. Oberlin remarked, their presence was even felt in France.