The Edict of Saint-Germain (1570) created strongholds

For the first time the Huguenots obtained ‘strongholds’. The Edict of Saint-Germain at the end of the third War of Religion (1568-1570) granted them four strong towns for two years, namely La Charité-sur-Loire, La Rochelle, Cognac and Montauban.

The legal invention recognised by statute was a compromise of the king to ensure confessional co-existence – in peaceful times the Protestants were allowed to keep a few military strongholds to be used as refuge, if need be.

The Edicts of Beaulieu (1576) and Poitiers (1577)

In 1576 as the fifth War of Religion ended, the Edict of Beaulieu used the idea of strongholds, granting the Protestants eight strong towns for an unlimited duration, namely Issoire, Périgueux, Serres, Nyons, Seyne, Beaucaire, Mas-Grenier (once called Mas-de-Verdun) and Aigues-Mortes.

At the end of the sixth War of Religion, the Edict of Poitiers (1577) granted seven more strongholds for six years, namely La Réole, Serres, Nyons, Seyne, Mas-Grenier, Montpellier and Aigues-Mortes.

The Treaty of Nérac (1579)

After the sixth War of Religion the Treaty of Nérac was signed in February 1579 in peaceful times. It confirmed the Edict of Poitiers granting the Protestants a total of fourteen strongholds for six or seven months, as applicable. But when the time was up the Huguenot community refused to give them back, considering those places no longer as refuge, but as an armed force to oppose the Catholic forces.

The treaty of Fleix at the end of the seventh War of Religion in November 1580, confirmed that of Nérac.

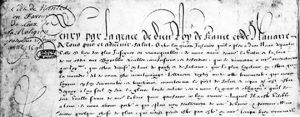

The Edict of Nantes (1598)

In 1598, the second secret letter supplementing the Edict of Nantes, which marked the end of the eighth War of Religion, allowed the Protestants to keep all the places, towns and castles they possessed in 1597. The Protestants then had 150 locations for refuge. It was the apex of the stronghold system – granting strongholds seemed the condition to accept the Edict of Nantes and peaceful coexistence.

There were different categories of places depending on the governor’s appointing methods, the men’s enrolment and the means of financing:

- Strongholds as such were towns where the garrison was financed by the king, who also had the power to appoint the governor;

- The so-called ‘marriage’ places, generally smaller, were appended to strongholds;

- the so-called ‘particular’ places were either towns without a Royal garrison and managed by a local council or by Huguenot lords, or places and castles held by Reformed lords.

Strongholds were mostly fortified towns or with a castle, such as Montauban, Nîmes, La Rochelle or Saumur. They could also be mere fortified manor houses used a refuge for the nearby population.

The future of strongholds

In 1598, the places were granted for eight years but were regularly renewed by Henri IV and Louis XIII until 1620, as requested by the Huguenot party reckoning the situation was still not safe enough to relinquish its own military power.

But as the threat of Wars of Religion moved away, justifying strongholds was less obvious. They were then considered by the Royal power as a ‘State within the State’, and the reinforced power of the sovereign and of his justice enabled to disarm the subjects.

In two phases, first with military campaigns in 1620-1622 and then in 1627-1629 when Louis XIII overtook all the Protestant military positions, as the Edict of peace of Alès in 1629 ordered the destruction of the walls of the last strong towns and castles still held by Protestant garrisons.