Refugees settled in Hesse-Cassel

The north of Hesse, also known as Hesse-Cassel, became reformed, or Calvinist in 1605, while Hesse-Darmstadt in the south became Lutheran.

Both Hesse and Brandebourg, which was also reformed, had suffered greatly during the Thirty Years War and for this reason the Huguenot refugees were made welcome.

Charles 1st of Hesse-Cassel (1671-1730) introduced laws to welcome the persecuted French Protestants and in particular those who wanted to establish their own firms or set up as craftsmen. The Huguenots founded firms for making silk, gloves, material and glass.

The Huguenots settled in the towns

In the edict of the 18th of April 1685, the Count, or landgrave, Charles of Hesse gave special favours and concessions to refugees who came to settle in his States; one of these was the right to have their own jurisdiction.

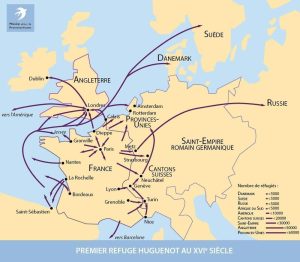

Following the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes the number of refugees increased greatly, 4000 people came to take refuge in Hesse and it became the second largest Huguenot community after Brandebourg.

The landgrave Charles 1st decided to establish two towns in Hesse-Cassel to welcome them and the architect was Jean-Paul du Rey, who was himself a refugee. These were the Nouvelle Ville Haute de Cassel and in 1699 Karlshafen, built on the foundations of a former mediaeval village.

These towns were administered by both French and German officials.

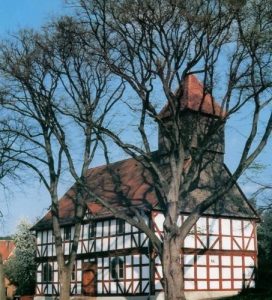

There were also many Huguenot villages in the provinces

Although the original project was for settlements in the towns, little by little the Huguenots also came to settle in the countryside. They founded twenty-seven settlements in the country during the 3 main waves of immigration, including Carlsdorf (Charles’ own village).

Usually they were built according to a very simple design, called the ‘ village along the high street’; the best example of this is Mariendorf.

From an economic point of view, few of these settlements could remain purely agricultural. Most of them were also local trade centers, the most popular one being the production of wool.

After the third generation most of these settlements had become well integrated (between 1760 and 1780) but they were never actually assimilated.

Although the landgrave guaranteed the teaching of French in these settlements, the situation varied from place to place. The French language was maintained the longest in Church ceremonies.