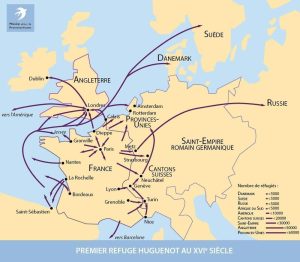

The flow of refugees to Germany

The thirty-year war (1618-1648) devastated a great number of German States. Huguenots looking for refuge after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes repopulated them, and were even a valuable source as they came from a prestigious country. Brandenburg in the duchy of Prussia received the majority of them.

Many came from border areas, for instance Metz and its region where the Protestant community was considerable, but also from Picardie, Champagne and Sedanais.

Others came from Southern France – Dauphiné, Provence, Languedoc, Cévennes- and were directed towards Switzerland. But it could not keep them all, and was only a stop on the way to the United Provinces and mainly Germany. Finally, those who had settled in the Palatinate during the first Refuge had to flee the troops of Louis XIV, who devastated the principality in 1689 during the war with the League of Augsburg (1688-1697).

The Lutheran free city of Frankfurt am Main, played the role of hub for the Refuge. Germany, being mostly Lutheran, the Huguenots chose Calvinist principalities, first Brandenburg, then Hesse-Kassel. Some settled in ancient Calvinist communities founded during the first Refuge, or in principalities of the Rhineland.

The Edict of Potsdam

The princely family of Brandenburg, the Hohenzollern, converted to Calvinism as early as 1613, without imposing it on the population who remained Lutheran, Calvinism being the religion of the Court.

Frederic-William (1620-1688), the prince-elector of Brandenburg, known as the Great Elector, published and circulated the Edict of Potsdam (the 29th of October, 1685*) granting French refugees particularly generous conditions to come and settle in his state devastated by wars. The edict guaranteed that emigrants would be taken charge of in terms of material assistance, passport, transportation to Brandenburg, freedom to choose the settlement place in the prince’s states, freedom of worship in their native language with a pastor paid by the prince, tax exemption for the first four years, option to occupy vacant housing or to build new houses with some help, equal rights and privileges as the natives, but especially naturalisation without any requirement to integrate immediately.

The Edict written in German and in French was widely circulated in German countries, in Switzerland and smuggled into France. The publicity continued under his son, prince-elector Frederic II who came in power in 1688, and was to become Frederic I, king of Prussia in 1701. During his reign the Huguenots had the same rights as German subjects, while keeping the privileges granted by the Edict of Potsdam, meaning that they had their own courts of justice, schools and French churches. 20,000 was the estimated number of refugees who took advantage of these offers. In 1700 a quarter of the Berlin population were of French origin. The French Church was very active comprising 9 pastors in 1715, building 3 temples and managing a hospital. Returns to France after 1768 were very few.

The situation lasted until 1809 when Frederic-William III abolished the specific constitution of Huguenot colonies, and granted them only the conservation of their religious and ecclesiastic organisation.

Contributions of the Refuge

One of the main contributions of the Refuge was demographic, the refugees helped repopulate sparsely populated areas after the damage caused by the Thirty-year war, epidemics and bad crops. The refugees came from more developed countries, and the first ones left a reputation of entrepreneurs, especially the 100,000 or so French-speaking Walloons who emigrated from the Netherlands to Germany.

Cultural development

The Huguenots played a key role in the foundation of the Royal Academy of Science and Letters in Berlin founded in 1700, two-thirds of its members being of French origin.

Prussia’s press was French-speaking in the 18th century. As in the United Provinces, journalism written in French was developing. The weekly literary gazette in Berlin, founded by Joseph de Fresne de Francheville, had a two-fold mission; the first was to give information on literary activities in Prussia, the second was to act as an intermediary for information from Paris.

In Berlin the New Journal of Scientists (1694-1689) was the first French-speaking scientific journal. After 1720 the Journal of Scientists became the Germanic Library, then the Literary Journal of Germany, of Switzerland and of the Northern Countries. Thus the Huguenots gave a French-speaking audience access to the German way of thinking of history, philosophy and law. German works written in Latin became intelligible thanks to translators into French.

Plentiful correspondence between Huguenot refugees played a major role in circulating cultural information and established a chronicle of the Huguenot Refuge in the 18th century. Amongst others, the letters exchanged between Elie Luzac (1723-1796), a philosopher and jurisconsult settled in Leiden and Jean-Henri-Samuel Formey (1711-1797), the perpetual secretary of the Academy of Sciences and Belles-Lettres in Berlin from 1748 to 1770.

Besides being journalists, many who mastered the French language found positions as private tutors. In Brandenburg former pupils of the French College in Berlin, who did not become pastors, were recruited by aristocratic or middle-class families in eastern or Central European cities, including Moscow and Saint Petersburg. These « unfamiliar though essential propagators in Enlightenment Europe » had a hard life, even truly “rotten jobs”, because of fierce competition. They were asked to teach everything, mathematics included, and French always being required. French young ladies were appointed to raise children and to teach them French. Samuel Formey, the son of a Huguenot,was perpetual secretary of the Royal Academy in Berlin and helped many of them find a job. The education of the princes and princesses of the royal family was almost always entrusted to French people.

The French language was not maintained equally in all regions. Besides the request to appoint a pastor, setting up a French school was not always accepted by the local authorities, as Frederic-William I called the “King-Sergeant” was not particularly favourable to the French influence. Conversely during Frederic’s reign the French language was in favour. As always cultural identity played a key role. Intermarriages rapidly germanized French names and led to the abandon of French. French continued to be used by the upper middle-class and the aristocracy. In Berlin, French Churches attracted people for quite some time, and so did a few French colleges. Madame de Staël claimed that as French was maintained, on the one hand assimilation was delayed, but on the other hand the social integration of the minority was eased thanks to mastering the language of European culture. French was longest maintained in the law and religious activities, but these slowly drifted to bilingualism. While the applications for French schools increased during the Napoleonic occupation, in 1814 Pastor Thérémin requested that French be forbidden during worship showing the French colony’s loyalty towards the Prussian crown.

Economic growth

The refugees introduced new styles of housing and diet. On the agricultural level the Huguenots revived a number of villages destroyed during the Thirty-Year War (1618-1648).

All social classes and walks of life were represented. Peasants, however, were less numerous than craftsmen who brought their expertise to the host countries.

In the industrial field, the Huguenots helped develop factories and popularise techniques, notably in the leather and textile sectors (especially wool and silk) in which they played a leading role, and created a luxury industry mainly aimed at meeting the requirements of the Court.

Prussia also benefited from the arrival of many officers, some of whom were experts in fortifications.

The traditional Hagiography of the history of the Refuge should probably be nuanced. In Switzerland, for example, the first refugees were confronted with the hostility of the local populations. Moreover, the local institutions, urban corporations and rural communities, jealously protected their interests and their independence, as they feared an evolution towards centralised absolutism, which could help the Huguenot population becoming more and more dependent on the State. Huguenot elites brought up in the ideology of an absolute monarchy were thankful and loyal to the Great Elector and his heirs, and thus became a unifying element. In that regard the Refuge contributed to the birth of modern Prussia.