Marguerite d’Angoulême and the beginnings of the Reformation

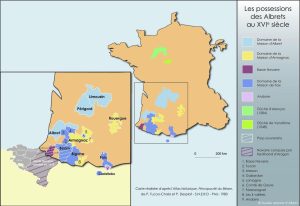

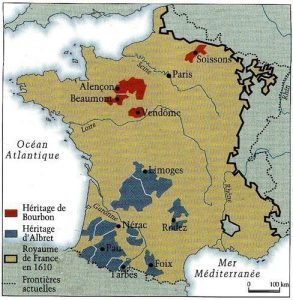

Historiography stresses the princely origins of the Reformation in the Béarn, Navarre, Bigorre, Albret and other territories which were all linked to the Crown of Navarre. Marguerite d’Angoulême, the sister of King Francis I and the wife of Henri II d’Albret, king of Navarre, who promoted evangelical ideas, played an undeniable role. She supported Gérard Roussel, her chaplain and former member of the Meaux Group, who was promoted to the bishopric of Oloron from 1536 to 1555. He tried to set up a pastoral and theological reformation in his diocese expecting a conciliatory solution to help the distressed Catholicism. He created a mass in seven steps but was questioned by the Paris School of Theology, as was his protector. However he never left the Catholic Church in spite of Calvin’s injunctions. Henri II d’Albret, who died in 1555, never responded to religious novelties, but his son-in-law Antoine de Bourbon and Jeanne his daughter, more sustainably so, were involved in promoting a reformation and helped it develop at the pace of the wars raging within France. King Henri IV, born in 1553, would witness and take part in the religious evolution of his mother. It should be noted that the religious legislation was supported by a group of people convinced of new ideas that permeated Béarn like other regions, thanks to commercial, intellectual and family exchanges.

Jeanne d'Albret’s reign and the implantation of the Reformation

At Christmas in 1560, Jeanne d’Albret symbolically took part in the Last Supper, and her 1561 ordinance allowed Reformed worship in her States under a simultaneum regime. Upon her husband’s death in 1562 she reigned alone. The methods of Jean Reymond-Merlin, sent by Calvin to help her reform her States, were too harsh for her as religious peace was reinstated in France after the first war of religion, but she turned to the moderate trend inspired by Jean-Baptiste Morely and established an ordinance on the freedom of belief. After 1566 she reconnected with Geneva and welcomed an emblematic character of the Reformaton, Pierre Viret, the famous Lausanne Reformer, and thus set up a Church in Béarn after the Geneva model.

The invasion of Béarn by Catholic troops

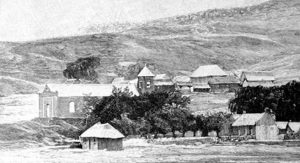

When Jeanne d’Albret held her court in la Rochelle with Coligny and Condé, during the third war of religion, she probably dreamt of a large Reformed principality in the Aquitaine region, but Béarn was invaded in May 1569 on Charles IX’s order by the Viscount of Terride supported by Catholic noblemen from Béarn and Navarre, who were against their sovereign’s religious policy. Pierre Viret was imprisoned in Pau, and seven pastors were executed. A ‘relief’ force, requested by the Viscount of Montgomery, drove the occupants out and released the stronghold of Navarrenx, who alone had resisted.

The Church ordinances of 1571

The only war of religion in Béarn gave Jeanne d’Albret the opportunity to achieve her work of Reformation: Catholic worship was forbidden. Priests were banned and Church property was confiscated to fund the new worship. Through her Church ordinances of November 1571, Jeanne d’Albret turned Béarn into a Protestant principality ruled by the declaration of faith of La Rochelle. The institutional outcome was undoubtedly the result of the deliberations of the Court of Navarre in La Rochelle, foreshadowing the French ambitions of the Protestant party before the Saint Bartholomew massacre but the formation of the Ligue put an end to their hopes. An assembly system enabled to rule a Church without bishops, and the limits were bound by the sovereign. Confiscated Ecclesiastical property were managed by the State and used to pay pastors’ salaries, to maintain buildings and to operate the academy.

The Reformation in Béarn

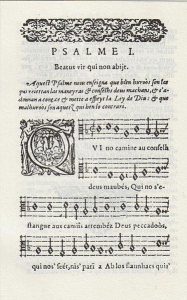

Though the Reformation was of French-speaking inspiration, the local language was used to spread the new faith ; in 1853, in Orthez, pastor Arnaud de Salette published a translation of the Psalms and of the ecclesiastical prayers of Geneva into Béarn language. An innovative school in the Orthez-Lescar academy was created in 1567, and was turned into a university in 1853. It was headed by important people such as Nicolas des Gallars or Lambert Daneau and aimed at training local administrative and religious elites.

Under the reign of Henri de Navarre and of his sister Catherine de Bourbon

Pierre Viret died early in the year 1571, and Jeanne the following year. Despite the recantation of young Henri after the Saint Bartholomew massacre, Béarn remained a Protestant Principality under the regency of his sister – Catherine de Bourbon. Her finances enabled to support the wars of Henri, who had become a Protestant again in 1576. Catholicism was only temporarily reinstated in 1599 by the Edict of Fontainebleau, a counterpart of the Edict of Nantes.

Béarn joined to France and Catholicism reinstated

In 1620, Louis XIII’s military expedition commanded that Béarn be joined to France, so that Catholicism could be fully reinstated with its worship and property. In the years that followed, Béarn, whose Protestants were mainly legalists, did not take part in the so-called wars of M. de Rohan, though they were partly caused by these events. Giving back the Churches, used for Protestant worship, resulted in an unrivaled wave of temple building, probably on an absidial architectural design, as testified in a drawing of Pau’s temple or in Arthez-de-Béarn’s vestiges, fatally damaged in 1998.

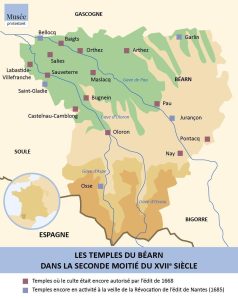

Under Louis XIV’s reign

There has been talk of the Protestant experiment in Béarn being a failure. But this term should be put into perspective because, though a half-century of State support was too short for the new faith to be durably implanted in a major part of the Principality, it was still maintained mainly in the Orthez and Salies-de-Béarn district. The end of the independence also impacted the religion of the elites, who partly went along with the sovereign’s religion. Lastly, the region particularly suffered institutional persecutions earlier than in France and in an exemplary way under Louis XIV’s reign when his main instrument was the Navarre Parliament: the Edict of 1668 reduced the worship places to twenty. The number was brought down to five in 1685 ; Intendant Foucault’s dragoons, sadly renowned for their persecutions in the Poitou region, forced Churches in Béarn to collective conversion.

The period of persecutions

The significant number of departures to England or Holland showed a spirit of resistance. The beginning of the Desert was a difficult period in Béarn, and the first meetings were cruelly smitten, Claude Brousson, for instance, was arrested after a visit to Pau as he was ready to leave Oloron in 1698. He was transferred to Montpellier and beaten up on the order of Lamoignon de Bâville, Intendant of Languedoc, who had relentlessly pursued him. The Protestants in Béarn laid low and did not follow the Camisard rebellion, but anchored their resistance in family worship, supported by the strong structure of the Pyrenean Ostau. This piety, encouraged by Jean Destremau, a former pastor of Bellocq, from Holland was maintained by writings that circulate under the bushel, (copies of sermons, prayers, theological treatises or controversy) and renewed by books sent in bundles of goods by refugee families in England.

Reconstitution of the Reformed Church

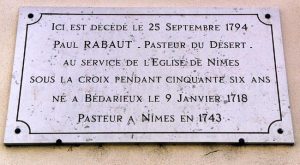

The presence of a preacher, probably of a Moravian tendency, was noted late in 1740 and prompted Paul Rabaul, who rebuilt Reformed Churches in France, to send a pastor to restore Churches in the Béarn region following the pattern defined by Antoine Court at the beginning of the century. In 1755, Etienne Defferre, a native of Gallargues near Nîmes, arrived in Béarn and spectacularly performed his task over less than two years: assemblies were held in broad daylight, christenings and weddings were celebrated, consistories were created. In 1757 he was joined by Paul Journet, a native of the Cévennes region, then by Paul Marsoô, the only pastor in Béarn at the time. The community in Orthez was supported by the influential middle-class open to the Enlightenment, whose influence managed to shelter it from the pressing undertakings of the parliament of Navarre. The community regularly wrote to the Court of Gébelin to win civil recognition for the Protestants whose christenings and weddings were not acknowledged.

The period however was not without problem. The Protestant Revival incurred the wrath of the local clergy who prompted the civil authorities to great waves of repression in 1758, 1760-1762, 1766-1767. On the basis of an agreement with the Intendant in 1767, the Protestants in Béarn switched from public assemblies to meetings in barns. They were quickly turned into Houses of Prayer which caused the last Dragonnade in 1778, the last to be inflicted in France. The glorious times however showed a decline in the community, incapable of proselytising and contaminated by ambient Malthusianism. Lastly, Protestantism was divided into two trends that announced the doctrinal discrepancies of the following century. A more urban trend, based on Enlightenment and Freemasonry, was represented by pastor Louis-Victor Gabriac who arrived in 1784 and was opposed to a more rural and more traditional evangelical piety, embodied by Paul Marsoô who was forbidden to practice his ministry in 1805, when the Consistorial in Orthez was created.

The first temple rebuilt in Orthez in 1790

The Edict of 1787 received a mixed reception, but the Revolution was embraced with enthusiasm and enabled Orthez to have the first rebuilt temple in France, dedicated on 25 November 1790. The façade bore the text ‘temple dedicated to Evangelical Christian worship’. In 1793, however, the Church was disorganised and turned into stables, as the Protestants in Béarn fell back on family worship.

Napoleon I reinstated Protestantism with equal freedom as Catholicism and Judaism in Organic Articles, a decree of Germinal year X. Though pastors were paid by the State, national Synods were abolished. Thus, after being illegal and then stifled by the Terror, the almost 5,000 Protestants formed the Consistorial Church in Orthez, that ruled over the district.

Le protestantisme béarnais au XIXe siècle

Ce qui caractérise le protestantisme béarnais au XIXe siècle, c’est d’une part l’exubérance des tendances, d’autre part l’exode de ses membres et enfin, le surgissement des “Œuvres”. Plus que partout ailleurs en Béarn il faut parler de protestantismes au pluriel : celui du Réveil marqué par un retour à la tradition calviniste conduit par le Vaudois Henri Pyt à Bayonne (1820), par Jacques Reclus à Orthez (1830), par J.-L. Buscarlet à Pau (1850) : celui de l’héritage des années difficiles marqué par les Lumières qui, lentement et difficilement poursuit sa réintégration dans le paysage religieux, contré par un anti-protestantisme sourd mais efficace dirigé par l’évêque de Bayonne. N’oublions pas les Anglicans et les Presbytériens anglais et écossais bien implantés depuis la fin des guerres napoléoniennes. Ils sont bien plus nombreux au milieu du siècle que les protestants français. Il convient enfin de citer le groupe darbyste venu grignoter les franges du librisme dans les années 1850. N. Darby, qui a vraisemblablement fondé son Église à Pau, prône une organisation plus égalitaire, sans pasteur. Il a pu séduire une partie de la communauté qui avait vécu de la sorte notamment dans le monde rural, durant toute la période du Désert.

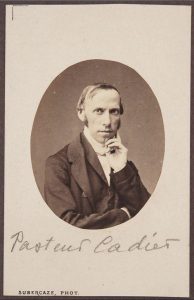

Le peuple protestant béarnais est violemment perturbé dans ses éléments majoritaires par l’exode rural. De 1880 à 1890, 10% émigrent vers les pays de la Plata, ou simplement à Orthez, Pau, Bordeaux, Paris. La nuptialité rare et tardive accentue le phénomène. En revanche, la population protestante urbaine connaît un essor remarquable : formée de descendants de Huguenots, de protestants alsaciens refluant après 1870, de nouveaux protestants issus d’une population catholique délaissée, de malades venant de partout, les pasteurs qui la dirigent ont une forte personnalité : Alphonse Cadier, recréateur vigilant et opiniâtre de la paroisse de Pau, Émilien Frossard à Tarbes et dans les stations thermales des Pyrénées, Jacques Reclus, pasteur tourmenté et intransigeant du troupeau libriste, Félix Pécaut, inventeur d’une morale laïque et créateur de l’éducation nationale. En fait, ce sont les “Œuvres” qui regroupent et soudent ce peuple protestant toutes tendances confondues. Les temples sortent de terre (23 de 1813 à 1906) ; les écoles ouvrent à Pau, Orthez, Bellocq, Sauveterre, Osse-en-Aspe jusqu’à l’ouverture des écoles laïques. Dès 1859, les mouvements de jeunesse – UCJG, UCJF à la campagne, scoutisme à Pau – dynamisent les adolescents (y compris les catholiques).

Toujours dans un souci éducatif, le journal Le Protestant béarnais est lancé en 1882, et en 1899 le pasteur d’Orthez, Jean Roth, crée L’Avant-Garde, ouvrant la voie à la tradition du christianisme social. Les bibliothèques de paroisse se multiplient et ouvrent leurs portes jusqu’à 10h le soir.

Évangélisation et mission en Béarn

Le troisième front d’unité est celui de l’évangélisation et des missions. En 1850 est créée la Société d’Évangélisation du Béarn qui œuvre en Bigorre dans les Landes, en Pays basque auprès des Bohémiens et des Juifs. L’Église libre s’intéresse aux Aragonais des environs de Pau (pasteurs Malan et Pozzi). Une commission spéciale pour l’évangélisation des Espagnols prend en charge le pasteur de Madrid, envoie des secours aux missions de Mahon et d’Oran. Joseph Nogaret, pasteur de Bayonne, prend sous sa responsabilité le travail missionnaire de Manuel Matamoros et crée une école d’évangélistes espagnols (1855). Eugène Casalis, d’Araujuzon, part en 1832 pour le Lesotho.

La loi de 1905 en Béarn

Le XXe siècle est inauguré par la loi dite de séparation de l’Église et de l’État (décembre 1905) et la formation d’associations cultuelles. Or, d’une part l’action commune de tous les protestants dans les “Œuvres” a soudé la communauté, d’autre part dans la mesure où l’essentiel du patrimoine cultuel est déjà construit et où les écoles protestantes n’ont plus de raison d’être (avec la communalisation) le régime d’association cultuelle est bien accepté. Parallèlement, l’effort d’évangélisation se structure : Oloron en devient le centre dès 1908, et Albert Cadier et son successeur Jacques Delpech créent la Mission Française du Haut Aragon. Si l’activité missionnaire en Espagne est entravée par la guerre civile (1936-1939), Jacques Delpech continue à agir de Genève et les équipiers de la CIMADE travaillent au camp de Gurs à sauver Juifs et Espagnols des camps d’extermination.

La présence des Anglo-saxons en Béarn diminue

La Première Guerre mondiale a désorganisé la présence anglicane et presbytérienne qui s’était considérablement développée dans la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle et qui avait marqué l’espace urbain de nombreuses constructions à Pau, Bayonne, Biarritz, Anglet et Cauterets. Toutes les tendances sont représentées, les presbytériens écossais, plus proches théologiquement des protestants français, et toutes les nuances de l’anglicanisme de la Low Church à la High Church et même le mouvement d’Oxford des catholiques anglais. En 1922, Christ Church est acquise par la seule communauté française (église de la rue Serviez actuellement). La Seconde Guerre mondiale achève ce départ : Saint-Andrew demeure à Pau le seul lieu de culte.

Le protestantisme béarnais à la fin du XXe siècle

À partir de 1945, les Églises protestantes doivent résoudre de nouveaux problèmes : la baisse de fréquentation des cultes, l’exode des jeunes adultes vers les centres universitaires (malgré la création d’une université en 1968) ne permettent plus un bon encadrement de la jeunesse. La communauté présente désormais un double visage : aux éléments traditionnels du fonds huguenot se mêlent des éléments de passage attirés notamment par le travail de l’industrie pétrolière. Elle crée des maisons de retraite et un Centre Rencontre et Recherche avenue Saragosse à Pau. Celui-ci a pendant une vingtaine d’années été le lieu de débats culturels, religieux, politiques très fructueux pour l’ensemble de la population de la capitale béarnaise. Soucieuse également de maintenir son identité culturelle et patrimoniale, elle crée à Pau en 1987 un Centre d’Étude, association historique, dont le siège est aux Archives départementales, recueillant les documents protestants depuis le XVIe siècle, conservés dans les Églises ou dans les familles, puis à Orthez en 1995, le musée Jeanne d’Albret, histoire du protestantisme béarnais.