The early days of the Reformation

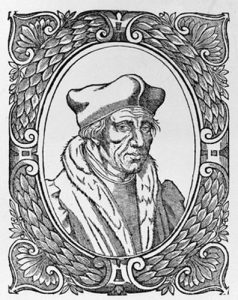

Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples (1450-1536), a great mystic scholar, preached a return to the Gospel. He was ordained as a priest and belonged to the group who wished to reform the diocese under the guidance of Guillaume Briçonnet, Bishop of Meaux. Expelled as heretical he found refuge firstly in Strasbourg and then came to Paris under the protection of Marguerite de Navarre. He published a commentary of the Psalms in 1512 and a translation of the New Testament in 1525. He is rightly considered a forefather of the Reformation.

Pierre Bully (circa.1500-1545), a Jacobin monk, was converted to the Reformation about 1540 after meeting Calvin in Geneva and then in Strasbourg. He was sent by Bucer to preach the new faith in Valenciennes and Tournai where he was burnt alive in 1545.

Guy de Brès (1522-1567) was converted to the Reformation after he was exiled in London from 1538 to 1552. He was a pastor in Lille and published Le Baston de la Foy-The Staffe of Christian Faith –, then in Amiens, Antwerp and Valenciennes. He was hanged in Valenciennes for celebrating the Last Supper. He is considered as the Reformer of the Netherlands.

The Reformation spreading in the Northern region

In the district south of Boulogne, Protestantism was attested to in the early1560s. Local noble families supported the Reformed ideas, opening their castles and manors to secret assemblies, listening to the word of God and singing psalms. For instance, the most famous castle was that of Claude de Louvigny at Wierre-au-Bois, and it was called the ‘castle-temple’ by the Catholics. It was stormed and burnt down in August 1572, the day after the Saint-Bartholomew massacre.

In the Cambrai district the rural population was influenced by Protestantism, and assemblies were held in the woods or in remote barns.

Escalating clashes

In 1555, after Charles V’s abdication, the Regent and his sister Marguerite de Parme tried to enforce a more strenuous religious rule over the whole district. But with German Princes joining the Lutheran Reformation, the death of Mary Tudor (1516-1558), who granted English Calvinists more freedom, and also with the nobility of the Netherlands supporting the Reformation, the international context strengthened the spreading of the ideas and the demands of the Reformed, who increasingly demanded places where they could meet. In spite of the prohibitions of Philip II, the son of Charles V and new King of Spain, assemblies of ‘heretics’ multiplied.

In the Summer of 1566, a revolt broke out in Steenvorde, a small town near Hazebrouck, which was called the ‘Beggars’ rebellion’ – after the name given to the heretics. Preachers worked up the crowds and the congregations around Lille, which was left unscathed, but Marcq-en-Bareul, Bondues, Croix, Wasquehal, and Valenciennes, considered as the ‘New Geneva’, were ransacked.

Unable to put an end to the violent demonstrations, Marguerite de Parme appealed to Philippe II who sent the Duke of Albe himself to the Flanders. He planned the repression methodically. Commissioners were appointed to make an inventory of the Protestants’ possessions to be confiscated. Capital punishments were numerous. Some who professed the ‘new religion’ but were not executed were banished. An estimated 12,000 left for England, Holland or Geneva where they founded Walloon or Flemish Reformed Churches.

From the late 16th to the late 17th century

While the Reformed movement was losing impetus in Artois, towards the end of the century, the population of the Calais district, from which the English were expelled in 1558, steadily grew again. The persecuted Huguenots from Artois and Flanders took refuge there and were joined by Dutch emigrants around 1600.

When the Edict of Nantes was signed in 1598, two temples were opened in Marck and Guines. A 3,000 strong community from all walks of life: Flemish farmers or craftsmen or rich Dutch merchants, helped one another and supported the most destitute.

Even before the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, defamatory proceedings took place, namely people arrested, worship places closed, and discriminations of all sorts that drove most of the population away.

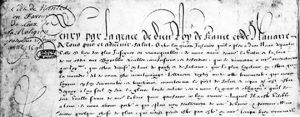

In the Boulogne district some noble and important families, who remained faithful to Protestantism, led a small community of about 350 worshippers in the late 17th century. They assembled at La Haye, a large fortified farm in Nesles, in the Pas-de-Calais département, where Reformed worshipping was proclaimed according article VII of the Edict of Nantes of 1598.

Several Protestants chose to be buried in a nearby meadow that was called the ‘parpaillots cemetery’ for a long time – translator’s note: parpaillot is a derogatory term for Protestant.

After 1672, however, preaching and burying authorisations were progressively revoked.

In 1685, the few remaining families in the area recanted leaving about 300 Protestant families in the Northern region.

19th and 20th centuries

In the early 19th century an active and influential though minority Protestantism was re-established under various circumstances.

At the beginning of the Concordat, Lille was the only city in the area with an official pastoral position. Protestants were few, but the community grew thanks to foreign families from England and Germany, who had come and created textile businesses in the region. The owners were greatly concerned by social issues and cared about the religious education of their workers.

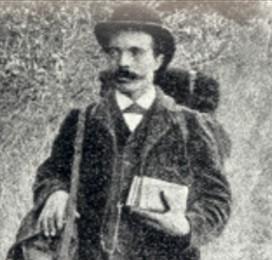

In the late 19th century the Revival Movement, partly inspired by the English Methodist pastor John Wesley (1703-1791), was introduced in Northern France by Tommy Fallot (1844-1904) and Élie Gounelle (1865-1950) and was met with a significant success.

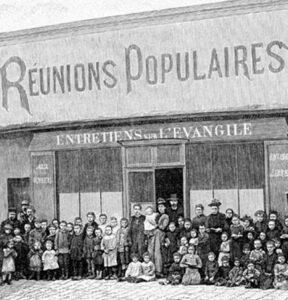

As communities were being established, Pastoral positions were created in Dunkerque, in Tourcoing, and in Roubaix where pastor Gounelle opened a meeting hall called ‘La Solidarité’. It housed many various charities: welcoming place, people’s university, workers’ circle.

In the mining area Protestantism was established later, thanks again to an Evangelical Society, the Christian Society of the North.

The working population massively took part in the meetings, which led to opening Protestant centres at Hénin-Beaumont, Liévin and Lens, and to building temples and presbyteries there towards the end of the century.

Another noteworthy evangelising figure in the North was Henri Nick (1868-1954), a pastor of the Reformed Church in Lille, who asked to be appointed at the Popular Mission in Fives, one of the most destitute districts in the city. He set up medical centres, addressed alcohol abuse, organised evangelical campaigns and debating to contradict important freethinkers. He organised holidays for workers’ children, supported them during the major 1930 strikes, and was thus present on all fronts of the workers’ struggle. But his action positioned itself outside the Social Christian Movement in the Northern region despite it being one of its main centres.

In Boulogne (Pas-de-Calais département) evangelizing the working-class was also a concern. Pastor Henri Pyt (1796-1835) was sent there by an English Evangelical Society, followed by The French Evangelical Society and later by the Popular Mission of the English Methodist pastor Mac All (1821-1893).

One can assess the decisive action of pastors outside the formal framework, especially concerning the regulation of child labour and the fight against alcoholism.

But the development of those initiatives, supported by Evangelical Societies of various origins and of many inspirations, harmed the unity of Protestantism so that there were 3 Unions of Churches in the Northern region the late 19th century:

- The United Reformed Church,

- The Union of Evangelical Churches,

- The Union of Reformed Churches (inspired from the Revival Movement).

It was only in the first third of the 20th century that a union of all the Churches could be contemplated, and eventually completed when the Église Réformée de France (E.R.F.) – French Reformed Church – was created in 1938.

The desire to evangelize and to help the most destitute was to remain one of the permanent features of the active and influential core of ‘Northern’ Protestantism. During the 20th century many Protestants were engaged in municipal, departmental and regional commitments.