The beginning of the McAll Mission

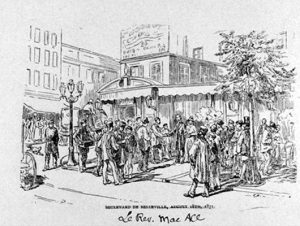

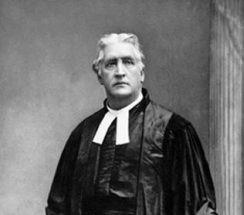

The Popular Mission began when the Scottish Protestant minister McAll (1821-1893) met the working people of the Belleville area of Paris in 1871, shortly after the Commune and the terrible repression which followed.

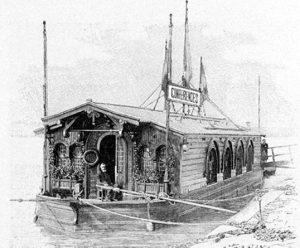

McAll was deeply concerned about the living conditions of the working class and their dechristianization but he also strove to fight against alcoholism and family violence. He understood that workmen wanted ‘a religion of freedom and reality’ and this finally led him to leave England for good and settle in France. He rented restaurants, barges, motor cars, ‘places where the seeds of faith could develop’ – in fact places which could be dismantled or moved after a service – so that ‘the Bible could be read, prayers said and the Holy Scriptures made accessible to all’.

At this time Protestantism was respected in France because of its modern attitude and encouragement of social progress, as opposed to Catholicism which was considered as ‘an instrument of superstition’ and disloyal to supporters of the Commune, who were in disagreement with officials in Versailles.

In order to present a valid alternative to social violence, McAll, and supporters who soon hastened to join him, were careful not to be judgmental about past or present political events and to be very tolerant towards those involved in them.

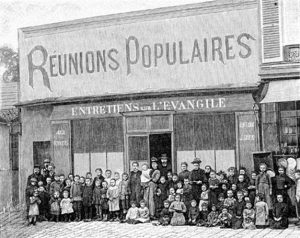

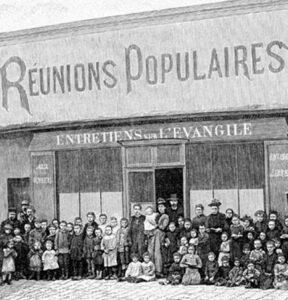

His meetings were more successful than he could ever have imagined. In the space of 20 years they were held in more than 50 towns, in places called ‘fraternities’ (of which there were more than 100).

They all operated the same way:

- An evangelical sermon on traditional lines which aimed at making new converts and was sometimes anti-Catholic.

- Attended by the poor and non-Christian.

- Social work, always associated with evangelization, in order to improve the people’s living conditions.

- An international financial organization based on McAll’s personal fortune and the support of many foreign donors.

By and large, those running the Mission – who we will call the ‘Permanents’ – had to ensure a good working relationship between:

- Workers on the ground seeking to alleviate poverty among the working class without a hidden agenda.

- Donors (mostly foreign) supporting the primary aim of the McAll Mission: to evangelize souls.

- French Protestant pastors and lay people who wanted new converts to join their own churches rather than missionary Churches over-concerned with social issues.

Indeed, for a period of 75 years, the Popular Mission, faithful to its original ideal, was close to the Social Christianity movement, sharing the same desire to change social conditions; the latter wanted ‘to change the social system in order to establish God’s justice on earth ‘ while the former sought ‘to change social conditions and individuals in order to save their souls’.

After the Second World War

After the Second World War there were many problems in society with the whole social infrastructure to be rebuilt. Many top members of the Church feared that Christian values would be progressively abandoned and that religious practice would cease in the working class because of the success of the Communist Party. Between 1945 and 1975 the Popular Mission went through a period of intellectual ferment.

Within the Catholic Church the ‘Working Priests’ movement indicated that they too were asking the same question: should one get to know the working man better before attempting to evangelize them?

On a more practical level, Pastor Francis Bosc (the brother of the theologian Jean Bosc) put these ideas into action in the Foyer de Grenelle, Rue de l’Avre in Paris. As well as evangelizing, help was given to workers to improve their living conditions without anything being asked in return. Within the French Protestant Church some considered that this work was political rather than evangelical. During the difficult rebuilding of society in the post-war years and the cold war, feelings ran high and the ‘Permanents’ of the Foyers were considered to argue with those they wanted to convince more from a socio-political than theological perspective.

For a period of twenty years, life for the Popular Mission was far from smooth and there were inherent difficulties because of the new direction in which it was heading:

- There should be no differentiation between believers and non-believers, Mission staff and the congregation.

- Some problems were solved through sociological analysis.

- The Mission felt closer to the working class than to French Protestantism, who they considered to be more teachers of the faith.

In 1964, the Teams of Protestant Workers were set up with the aim of meeting the working man in his place of work, but gradually the religious dimension ceased to exist, so some members of the Popular Mission no longer supported the movement.

Even though it was still a member of the Protestant Federation of France in 1969 tensions remained: for some there was over-emphasis of politics, for others, it was the real effort made by the Eglise Réformée to deepen their knowledge of the working class. However, since 1980, ideas have been based on values held by all.

In 1992, the Congress of Ecully reaffirmed the ideal of the Popular Mission: “to be based on the Gospel and companions of the socially outcast”.

The main role of the Popular Mission is to try and respond to the new religious needs of the working class and to stand for traditional Protestant values: a critical mind, individualism but, above all, to live according to the Gospel.