The reign of James I (1603-1625)

When Elizabeth I died, James VI of Scotland (James Stuart) came to the throne, he was known as James I of England and VI of Scotland ; in this way, Scotland and England were united at last. As he had been brought up a Calvinist, the English Calvinists had hopes of England becoming Presbyteria but they were soon disappointed when he converted to Anglicanism. As he had complete power in the realm of religion, it was a temptation to also have complete power in politics as an absolute monarch. He did, however, allow Anglican priests a certain amount of freedom in the way they led their services and their use of the liturgy in the Prayer Book. Those who rejected the sign of the cross and the practice of kneeling were not persecuted ; in fact the Church of England was popular with most of the population around 1620.

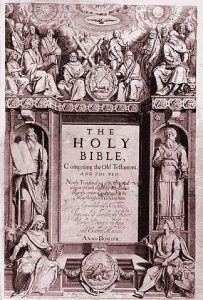

There was, however, a small minority of Calvinists who were in opposition to the Church of England. They were persecuted and some emigrated to the Low Countries or to America (the “Mayflower” pilgrims in 1620). King James 1st considered the Geneva Bible to be too Calvinist, so he had it replaced by a new translation (the “King James” version). This was the work of 47 scholars, much loved and had a great influence on English literature – it was so popular that its use extended right into the XXth century. Even though people were allowed to read other versions in private, this was the only version to be officially used in the churches.

The reign of Charles I (1642-1649)

James’ son Charles I believed in absolute power and he tried to impose his authority on Parliament, who objected violently. He appointed Laud as archbishop of Canterbury and with his help, tried to impose more rigid rules on the way the Church of England conducted their services. He forced priests to follow the Prayer Book to the letter and to wear special religious ornaments. As for the congregation, they had to kneel for communion, make the sign of the cross etc. He had the churches decorated with religious images. So much so, that many Englishmen had the impression that Laud wanted to bring back Roman Catholicism. And as for the Calvinists, (who had managed to survive without too much harassment under James I), many now openly broke away from the Church of England. In Scotland, Charles 1st imposed Anglican rites and especially the Scottish Book of Common Prayer on the Presbyterians. In spite of opposition from the clergy and Church members he continued to impose his will. This led to armed rebellion. In order to put it down, the king had to call Parliament, which had not met for eleven years. In the House of Commons those who opposed the king held sway and the country was plunged into civil war.

Civil War (1642-1649)

At first the civil war was a conflict between the king and Parliament. However, this soon took on a religious aspect when the Scottish Presbyterians and rebels against Laud decided to support Parliament. In the first Act of Parliament, Laud was dismissed, later imprisoned and finally executed in 1643.

Since Parliament and the population of London were in open rebellion against the king, he decided to leave London for Nottingham, where he raised an army. The Civil war consisted of a conflict between the “Cavaliers” who supported the king (Anglicans, noblemen, farmers) and the “Roundheads” who supported Parliament (Calvinists, the urban middle class and minor nobility). At an early stage of the war, Oliver Cromwell came to be recognized as an outstanding leader ; he was a country gentleman who had raised a Roundhead army at his own expense, which was organized on democratic lines with elected officers. Parliament appointed him General Lieutenant of the cavalry and his role was to totally reorganize the army which was then renamed “the new model army”. His officers often led the prayers or preached at church services. Cromwell led this army to a resounding victory against the royalists in 1645. Charles 1st fled to Scotland but the Scots handed him over to Parliament in 1647. The latter wanted to reduce the power of the king but not necessarily abolish the monarchy. However the army seized power and when Charles I tried to escape, Cromwell took the opportunity to crush Parliament. The new Parliament, consisting only of extremist puritans, sentenced the king to death and he was executed in 1649.

Oliver Cromwell

In 1649 England became a Republic, although only a minority of the population were actually republicans. Oliver Cromwell was appointed lord-protector in 1653 and his position resembled more and more that of an absolute ruler.

Parliament had already abolished the episcopacy and the Prayer Book since the beginning of the civil war in favour of a Presbyterian system which was in fact only applied in London and Lancashire. Oliver Cromwell was not a Presbyterian but an “independent”, believing in the “reign of saints” that is to say, the reign of the puritans. This religious tendency gave rise to many new communities and its most eminent member was the great English poet John Milton.

The puritans

The name “puritans” was given around 1560 to a certain group of Calvinist protestants who wanted further reforms to be carried out within the Church. They objected to priestly robes as they wanted to purify the Church of anything ornamental. They wanted a simpler kind of liturgy and refused strict obedience to the Prayer Book. However their main reaction was to the Episcopal system which they wanted to abolish in favour of Presbyterianism ; this led Elisabeth I to install a violent regime of repression against them.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the puritans welcomed James 1st favourably. When he converted to Anglicanism some began to emigrate to America, but most of them remained members of the Church of England, who did not reject them. In the reign of Charles I they became actively involved in opposing the king and in the civil war the puritans, victorious, seized power under Cromwell’s Protectorate. However, the puritans as we know them, renowned for their austerity, strict respect for morality and the Sabbath, did not actually form a united group. On the contrary, there were various different tendencies:

- The Presbyterians were the majority. These Calvinists wanted their ministers to be free to preach the Gospel and a Presbyterian system to be established within the Church ;

- The Congregationalists or independent Church (of whom Oliver Cromwell was a member), were also Calvinist, they but wanted total autonomy for their parishes. In Cromwell’s reign, some parishes became Congregationalist and other, new parishes started up alongside those which already existed. They were led by ordained ministers.

- The Baptists practiced adult baptism – this was necessary to become a member of the Church, or a “saint”. They were influenced by the Dutch Mennonites, the modern equivalent of the Anabaptists. Some remained Calvinists but others rejected predestination. Moral discipline was strict.

- The millennium communities attracted members at times of political or religious crisis. They sought their inspiration in the books of Daniel and Revelation, which they used to justify the idea that Christ would reign for a thousand years and the year 1666 was the apotheosis of such an expectation (this was because 666 was the number of the beast in Revelation). Some communities tried to set up a new social and political order to establish a new Jerusalem. However, since the millennium did not actually happen, these somewhat ill assorted movements tended to disappear little by little. They were often led by “inspired” leaders.

- The Quakers, or tremblers were part of these “inspired” groups. They thought that the inner light in a human being was more important than Scripture and that everyone could have this light. George Fox, the founder, was an inspired layman. He rejected any form of worship or hierarchy and proclaimed brotherhood and equality among men. His “Society of Friends” was founded in 1688. At their meetings, Quakers would express their inner inspiration by improvised speech, gestures and expressions of enthusiasm or by trembling – (to quake = to tremble). George Fox was insolent towards the clergy and magistrates – as a result he was imprisoned several times. His charisma and gift for organization enabled the movement to survive even when it was persecuted in the reign of Charles 1st. At this time the emphasis was on pacifism, mysticism and the search for the Kingdom within oneself. The Quaker William Penn, the son of an admiral, studied in France with Moïse Amyraut and went on to found the colony of Pennsylvania in America in 1682.

- Although their refusal of military service and the taking of oaths for the authorities caused them many difficulties, their spirit of tolerance, social work and educational institutions made them pioneers of the ages to come – it was thanks to their influence that the future anti-slavery and human rights movements were able to achieve their aims.

The restoration : Charles II (1660-1685) and James II (1685-1688)

When Cromwell died in 1658, his son Richard and successor came into conflict with the army and had to abdicate. The English no longer wanted anything to do with military dictatorship so they called on the son of Charles I to be king in 1660, under the name of Charles II. This was after he had promised a general amnesty and freedom of conscience. Charles II restored the Church of England and the episcopacy. There were attempts at altering the Prayer Book in favour of a more Presbyterian approach but these failed and 20% of the ministers left their parishes. The puritans (or dissenters) were persecuted : they were not allowed to have meetings or hold public office in their local community and were imprisoned. 8,000 people were imprisoned on religious grounds, among whom there were many Quakers and Baptists. The most famous prisoner was John Bunyan, who, while he was behind bars, wrote his famous book, The Pilgrim’s Progress which would become the most translated book after the Bible.

Charles II’s brother James II (1685-1688), a convert to Catholicism, became king and swore an oath to defend the Church of England. However, he had many Jesuit friends, who drew the animosity of both Anglicans and dissenters. When his son was born, his adversaries called on James II’s son in law, the Dutch stathouder William of Orange, who was recognized as a royal regent when the king escaped from the country : he later became king and his wife Mary became queen. They were known as William III (1689-1702) and Mary II.

William and Mary (1688-1702) : the Glorious Revolution

When the Calvinist William of Orange and his wife Mary came to the throne, there was no violence or bloodshed. This is why the English call this period the “Glorious Revolution“. The new sovereign led England and the United Provinces into the Nine Years’ War (also called the War of the Grand Alliance – Ligue d’Augsbourg) against Louis XIV; at one stage this raised the hopes of the persecuted protestants in France, but they were soon to be disappointed.

From the religious point of view, this was a peaceful time, but 400 priests and 6 bishops, out of loyalty towards James II and the Stuarts, refused to swear allegiance to William III and they were evicted from the Church of England. On the other hand, the king, a Calvinist, tried to reintegrate the Presbyterian pastors into the Church of England but he did not achieve his aim. The most important act to be passed during this reign was the Act of Tolerance on 24th May 1689, which raised the sanctions against the “non-conformists” – that is to say the protestants who were not part of the Church of England – and gave them places of worship on condition they swore allegiance to the king. This was an era of relative tolerance towards religious minorities, excluding the Catholics.

Gradually a spirit of rationalism and tolerance spread throughout the country. This gave rise to a new movement within the Church of England which aimed at putting an end to theological disputes – the accent was put on moral reform and piety rather than dogma and church government. It was called the “Low Church” and its pastors gave new energy to the Church of England through their enthusiasm and example.

As none of William and Mary’s children survived, the king and Parliament voted the Act of Succession in 1701, which excluded any catholic monarch from the English throne and gave the succession to Ann, Mary’s sister, a protestant, then, to the House of Hanover.