The Huguenot State was set up in reaction to the excessive power of the monarchy

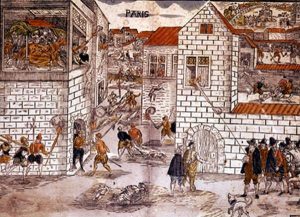

There was relative peace in France after the Treaty of St Germain in 1570, which gave Protestants a certain degree of religious freedom and four strongholds. Catholics and Protestants lived peacefully together until the St Bartholemew Massacre in 1572, which brought this situation to an end, forcing many Protestants to escape from France.

However, not all Protestants decided to leave the kingdom – some gathered together and founded a community establishing a kind of Huguenot state similar to its Dutch counterpart and called the United Provinces of the South. This was not a true comparison because the French structure was not a Free State but under the domination of another sovereign State, unlike the case for the Netherlands.

It was made up of local communities and had been founded in Millau in 1573. Each province had a certain degree of independence; their General Assembly elected the following Protectors: Henry of Condé until 1574 followed by Henry of Montmorency-Damville until he joined forces with Henry III in 1577 and finally Henry of Navarre.

Its organisation

The union consisted of the following provinces: the Poitou, the Languedoc, Provence, the Dauphiné and the Massif Central. It was essentially an urban structure which included all social classes and its aim was the peaceful cohabitation of Catholics and Protestants.

The General Assembly was made up of deputies from provincial assemblies, and met every six months. It elected a permanent council of four members and a military leader – it was as powerful as a sovereign state with a capacity to conduct diplomatic, tax, legal and military policies.

The Provincial Assemblies, made up of representatives from towns and villages, met up every three months and chose a permanent council and a military governor.

Its aims

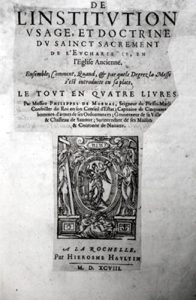

The Union’s aim was. not to break away from the kingdom and establish an independent state. On the contrary, there was a clear affirmation of loyalty to royal institutions, even if the followers of a moderate monarchy regime considered that certain royal decisions were unacceptable and there was increasing misunderstanding between the leaders of the Huguenot State and the local representatives of the royal administration. The Union’s only aim was ‘to give glory to God to bring about Christ’s kingdom, to serve the Crown and strive for its wellbeing, to achieve peace for all in this kingdom’ However, the conditions which Protestants had to accept at the time, amid constant threats from the Catholics in power, did not always mean that the Union by its aims; also the General Assembly evolved, both in the social and geographical level of its representatives, so that it became an ideal implement in the hands of Henry of Navarre when he was calculating how to seize power.

How the Huguenot State evolved

When the State first began, the federal deputies came from regions where there were the most Protestants and from the Languedoc in particular. There were many militant Protestants at the Assembly in Millau. Later, this situation changed, however, and from 1581 onwards the provinces of the South sent many deputies; by 1585 at the Assembly in Montauban, most of the deputies came from the West. In fact it was those regions influenced by Henry of Navarre who had the most power in the Assembly.

It was not only the geographical situation which changed – the social level of the deputies of the Federal Authorities also evolved. In 1573, there were only a few aristocrats but in following assemblies this was no longer the case and the monarchists became the most powerful group.

The governing provincial body remained the same as at the beginning; composed of lawyers, squires and pastors.

The Protector took complete control of the Huguenot State

In 1577, Henry of Navarre ‘first prince of the blood’, became the Protector of the Huguenot State; he established his power by placing his supporters in the federal authorities. He taxed both Catholics and Protestants alike and decided to reserve a large part of the State budget to the financing of troops defending the Protestant cause. In this way the Huguenot State became a military structure which was much needed when army raids were carried out into Protestant territory by the troops of the king, who sought to impose Catholicism and centralize power.

What the Union of Provinces achieved

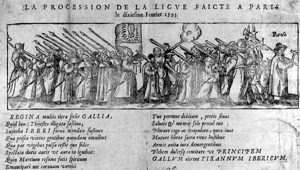

The main achievement of the Union of Provinces was to have created and maintained unity in the South of the kingdom, first against Montmorency-Damville when he decided to support King Henry III and later against the Catholic League in 1588.

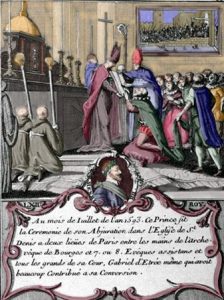

When Henry of Navarre became both Protector of the Huguenot State and heir to the French throne after the death of the Duke of Anjou in 1584, there was a convergence of aims for the Huguenot State and its Protector. In fact the Huguenot State became quite naturally part of Henry IV’s increasingly centralising governing policy.

The Union of Provinces maintained a lasting administrative and judicial authority in the South of the kingdom. It enabled Henry IV to take power quickly and establish order because it was indeed already part of his kingdom. To quote Janine Garrisson, the question is “whether this strange country had ever been anything other than a purely fictional existence on paper”.

One can agree with this view and consider that it had never been much more than the preparation for the conquest of France by Henry of Navarre. It was not a state – there are no visible signs of its existence, but a true Union of Provinces which was instrumental in Henry of Navarre’s conquest of France both before and after he came to the French throne.