The Cardinal's ambivalence

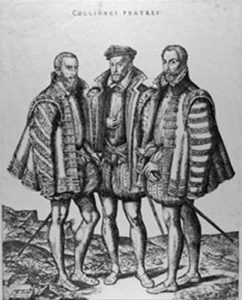

Odet de Châtillon, even more than his two brothers, was influenced by the education he received from the humanist Nicolas Bérauld, but also by the evangelical piety of his mother, Louise de Montmorency.

Thanks to his influential family Odet, was made Cardinal when he was 16. The following year he was made Archbishop of Toulouse and prior of many abbeys. In 1535 he became Bishop of Beauvais.

During the 1550s as the tensions between the Catholics and the Protestants grew, the ambiguous attitude of the Cardinal made him look heretic. The historiographical tradition tells that the Cardinal converted to Calvinism at the castle in Merlemont (Oise) on Easter Sunday 6 April 1561, as he practised the Holy Communion under both kinds. But it was not so. Châtillon did not act as a Protestant but as a living example of the deep reformation of the Catholic church he advocated: the Holy Communion under both kinds, a more internalised faith freed of what he called superstitions, and, we may assume, the permission for prelates to marry, as his affair with the young and beautiful Isabelle de Hauteville was notorious at the court.

He was allowed such freedom thanks to the unconditional support of Catherine de Medici, as one of her favourites, and to his friend Michel de l’Hospital. Along with them and Jean de Monluc, Bishop of Valence, he belonged to the mainstream moderate Catholics at the Council of the King. That was why he totally committed himself to the compromise between Catholics and Protestants initiated at the Colloquium of Poissy in the early 1560s, then in negotiations with the papal legate in 1561, where he tried to inflect the Catholic dogma so that Christian Churches could unite. But to no avail. Odet de Châtilon’s religious commitment was not understood.

A long conversion process

During the first war of religion (1562-1563) the Cardinal of Châtillon suit aside his bishop’s purple. As soon as the Peace of Amboise was signed, he took it back for good and attended mass again. This attitude, condemned by inflexible Catholics, was tolerated, even encouraged by the Calvinists, who believed that his presence at the King’s Council could help their cause. Their idea was to allow the Cardinal time to decide when to reveal his commitment, which could no longer be doubted. In July 1563 Odet de Châtillon had been officially excommunicated from the Apostolic and Roman Church. In 1564 he married Isabelle de Hauteville.

Rejected by the Catholics, Châtillon kept his religious feelings hazy. It was only in 1567 upon the restructuring of the Huguenot party that he officially committed himself to the Protestant cause.

The diplomat

Due to his exceptional skills as a diplomat and to his very good relation with Marie de Medici and Charles IX, he negotiated the best part of the Peace of Longjumeau (March 1568). Thus he made it possible to end the second War of Religion that his brother was instrumental in starting.

The edict of pacification was short-lived, as early as the month of August, war was declared again and Châtillon had to flee to England. Within a few weeks he won the favours of Queen Elizabeth I, but could not convert them into material and financial backing for the Huguenot party.

Upon the peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (8 August 1570) he stayed in London but at the service of Catherine de Medici – the queen-mother meant to use his good relations with the Court of England to negotiate the conditions of a marriage between the British sovereign and the Duke of Anjou (King Henri II to be). But the negotiations finally failed. On 21 March 1571 as he was ready to embark for La Rochelle he died of such a rapidly fatal disease that poisoning was suspected. He was buried in Canterbury Cathedral.