The embraced Revolution 1789-1792

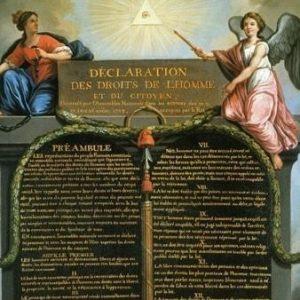

In its early days the Revolution was enthusiastically welcomed. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen affirming the freedom of faith, and access to all State functions for every worthy citizen was warmly welcomed by the Protestants. Ministers of any religion were asked to officiate at the altar of the Fatherland, upon celebrations of the Federation in June 1790.

The Civil Constitution of the Clergy in July 1790 allowed for bishops and curates to be elected by all the citizens, whatever their faith, which made the Catholic Church emanate from the Nation, a complete break from the principles of Catholicism.

Privileges were abolished in the night of the 4th of August, 1790. Then the property of the clergy was made available to the Nation on 2 November, which scared the Protestants, even though the property of their Churches was provisionally excluded from sales, a favour frowned upon by the Catholics.

As the Protestants feared being included in a system that would not take account of their specificity, they set up a civil constitution project for the Protestant clergy, with the parish as a basic unit. The project was submitted to the National Assembly who did not comply, even more so as many parishes were against it.

Cordial relations were established with the constitutional bishop of Strasbourg. People took part in every patriotic event, flags were blessed by curates and pastors. An oath of loyalty to the Nation and the king was sworn.

As the Revolution had maintained the autonomy, the freedom and financial security of Protestant Churches, Alsatian Protestants displayed unwavering patriotism. They took part in the memorial service upon Mirabeau’s death.

The Terror

After the Parisian riot on 10 June, 1792, the defeat of the constitutional party and the overthrowing of the monarchy, some municipalities decided on a restrictive policy concerning worships. After the Republic was founded on 22 September, 1792, civil registration was introduced and pastors feared that they would no longer be able to keep records of baptisms, marriages and burials. In February 1793, commissioners on mission aimed to proceed with the sale of parish property, but the initiative was turned down by the Convention.

After the defeat of the Girondins in June 1793, the Mountain became all-powerful. In Strasbourg among the ‘Friends of the Constitution’ the ‘moderate’ Protestants were called the servants of the mayor, then the Protestant Jean de Dietrich. Some radicals in the Jacobin Club made hostile statements about the Protestants, accused of arrogance towards the Catholics, and to payments by the wealthy Lutheran Saint Tomas foundation’.

The declaration of war against Austria caused the radicalisation of the regime and the installation of the Terror. Representatives of the people on mission launched a massive purging of all elected bodies. Denunciations increased, a revolutionary court of justice was set up in Strasbourg, and prisons were filled. Protestant figures such as Blessig, Lobstein, or Haffner were imprisoned along with many priests already held for months.

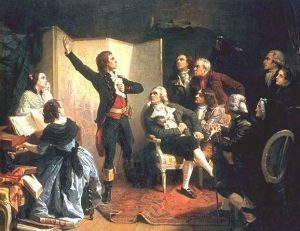

The guillotine worked. The first pastor was executed in November. The former mayor Dietrich, in whose house Rouget de l’Isle had composed the Marseillaise, was accused of treason with the enemy and executed in Paris in 1793.

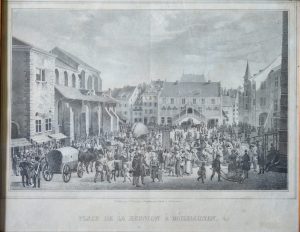

All worship buildings were commandeered, and precious items sold. The cathedral was turned into the temple of Reason, and its spire topped with a tin Phrygian cap. About twenty pastors out of 220 declared their abjuration and did not resume their ministries after the Terror.

Repression was particularly important in Strasbourg but less in the Haut-Rhin region. In the countryside the situation was less tragic, especially as the revolutionary propagandists did not understand either the Alsatian language or mentality. Worship was disguised as patriotic sessions, pastors often had to hide, but in some places they could celebrate worship until July 1794. The arrest of all ministers was then decided, but the fall of Robespierre put an end to the excesses.

It should be noted that the Protestant left-wing took part in political and civic actions. The ‘popular society of the friends of liberty and equality’ united disinterested Catholic and Protestant idealists, and worked intensively to serve the common good, especially education. The Society was busy appointing qualified schoolteachers for the new national schools set up to replace forbidden denominational ones, and also the High School in Strasbourg.

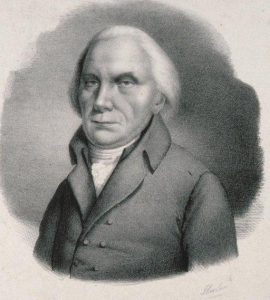

Pastor Oberlin, a major personality of the mouvement, was arrested in spite of repeatedly testifying of his republican public spirit, but fortunately freed at Sélestat on the 1st of August, 1794.

The attempt to replace traditional religion by philosophical ideology having failed, several decrees, dated February and May 1795, reinstated the freedom of religion, and gave confiscated property back. The resigning pastors were more difficult to replace, as reorganising theological teaching was needed. To solve the financial problems due to unpaid municipal services for some years, parishioners were asked to contribute.

The Directory

In 1798 under the Directory, from October 1795 to November 1799, the free city of Mulhouse joined the French Republic.

Many pastors kept the grandiose style of the time. Pastors had to pledge the civic oath again. Hymns were in German and preaching in French praised civic virtues. The public authorities only considered the Protestant population as ‘tolerant, moderate and outstandingly submitted to laws’.

In 1799, some Jacobin representatives asked again that the property of Protestant Churches be seized. But the Directory did not wish to upset the Protestants, hesitated, and eventually Napoleon Bonaparte’s coup on 18 Brumaire Year VIII (9 November, 1799), ended the dispute.