Who were they ?

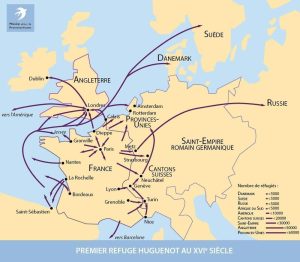

In actual fact, this emigration only concerned a very small minority of the 200 000 protestants who left France after the Revocation of the edict of Nantes. From 1688 to 1691, only 178 families (which makes less than a thousandth of the total number of protestant refugees from France), travelled to South Africa on 4 ships, the biggest being the Osterland. They came from two main regions in France, one region consisted of the arch stretching from Flanders to Saintonge, the other region consisted of the arch stretching from the Dauphiné to Languedoc, which includes Provence.

The Huguenot emigrants were different from the Dutch and German settlers who made up the average population of the Cape Colony. These were especially poor wretches living in desperate circumstances or mercenaries who had been unemployed since the end of the 30 years war. The French protestants, on the other hand, who had fled because of religious persecution, mostly belonged to the bourgeoisie and what’s more, a quarter of them even had typically aristocratic names, judging from the passenger lists.

The East India Company

The Cape Colony was at the time an essential port of call on the route to Batavia for the ships belonging to the Dutch East India Company. The Colony was an extremely rare example historically of a country which was entirely run as a business enterprise.

Why did the “17 powers” (that is to say the 17 administrators of the Company) ask the Huguenots to come to the Colony ? For two main reasons :

- The first was a real desire to help people who shared the same religion as themselves – indeed, this was according to the religious principles of the Company.

- The second reason was of direct benefit to the Company ; they needed to develop agriculture in order to provide fresh supplies of food for the ships on their way to Batavia. An essential ingredient in these supplies was wine, which kept better than water on board ship. Up until then they had not managed to grow vines successfully so when they were making their choice of volunteers at the beginning of this venture it was of great importance to have expert knowledge in this area of agriculture.

The journey to the Cape

Strict conditions were imposed by the Company on those wishing to emigrate ; no luggage was allowed, the journey was free, on condition that the emigrants kept to the rules, one of which was the necessity of staying in the Cape for at least five years – after this period of time they were allowed to return, but they had to pay for the journey. The Company promised the Huguenots that on arrival they would receive as much land as they could cultivate – in actual fact they received 30 to 60 morgen, that is, about 15 to 60 hectares, (maximum about 100 acres) as well as the necessary tools and seeds.

The 6 week long journey was fraught with dangers of every sort : storms, pirates, the king’s vessels, and especially illness, with scurvy being the worst. However, notwithstanding these bad travelling conditions, all four ships arrived safely in South Africa.

How they were received

Since they had previously been given a warm welcome by the Dutch, the Huguenots were well received by the Governor, Jan van Riebeeck, whose wife, Maria de la Quitterie, was French. To start off with, his successor, Simon van der Stel, was also favourable to the Huguenots.

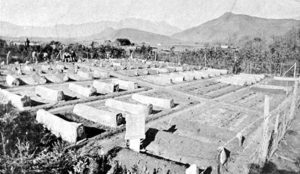

They settled about sixty kilometres north-east of the Cape, between Paarl and the area which was later to be called Franschoek (“the French corner”). In spite of the fact that the ground was fertile, it was quite overrun with scrub and they spent at least three years clearing it in order to be able to start growing any crops. What’s more, the Company did not keep its promise concerning the agricultural equipment they had said they would provide.

Although they started off on good terms with the Governor and his son, the Huguenots came to realize that little by little, the situation was deteriorating, probably due to a misunderstanding about their future role in South Africa. Whereas the Company wanted the Huguenots to integrate and become “good Dutch farmers”, the French, on the other hand, clung to their language and their traditions. As long as Pasteur Pierre Simon was there, with his parishioners, they maintained their French identity. But when he left, the newly arrived Huguenots were not allowed by the Company to have French pastors or primary school teachers and the result was that by 1730, the French language had completely disappeared, in less than two generations. Never before in the history of French emigration had such a thing happened.

What have we inherited from the Huguenots today ?

Although it was difficult at first, the French settlers soon thrived as farmers and became wealthy in the course of the XVIIIth century. When South Africa was conquered by the English, few of them took part in the “Big Trek” in 1836 ; this was the migration towards the northeast of the country and led to the foundation of the Free State of Orange and of the Transvaal.

What remains of all this today ? We can say that there are roughly three factors to consider :

First of all, names : 20% of Afrikaners, the white non-English population, have French names ; the telephone directories are full of them ! You can find Du Plessis, De Villiers, Du Toit, Joubert or Marais ; some of them have been assimilated into the Dutch language : Leclerc has become De Klerk, Villon has become Viljoen, or Rétif has become Retief, etc. The farms near the Cape have also kept their original names, connected with places, such as La Motte, L’Ormarin (for Lourmarin), La Brie, Picardie, Chamonix, etc., or they may have a connection with religion, for example Bethléem or they may simply be poetic, such as Plaisir de Merle, (The Blackbird’s Delight) or La Concorde (Peace).

The second factor to consider is the tenacity of religious tradition ; it is said that if Calvin came back on earth, it is in South Africa that he could be found ! Indeed, the Dutch Eglise Réformée has not changed by one iota the protestant liturgy of the time, nor the hymns by Clément Marot and Théodore de Bèze, in their original translation, set to music by Gaudimel. We can trace back the tradition of daily Bible reading and its literal interpretation to this period, when the Huguenots did not have any pastors to guide them. Indeed, tragically, it was this literal interpretation of the Bible which led to the theory of apartheid. Lastly, South Africa is a church-going country and the church parish still remains the centre for family and community life today.

The third factor is that in spite of, or because of their assimilation, the Huguenots have contributed greatly to the creation of the Afrikaner spirit, notwithstanding the fact that they were few in number. It is as if, since they could not remain French, the least they could do was to become the spearhead of this new country. In the little Huguenot museum in Franschoek, their influence can still be seen. Here, a great deal of emphasis is laid on the fact that many French names can be found in the fields of politics, finance and rugby.