Forty galleys needed rowers when Louis XIV was in power.

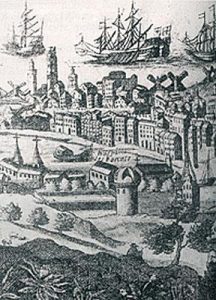

The galleys were used as detention facilities rather than warships. They were abandonned in 1748 and replaced by convict prisons in navy ports, or arsenals. Louis XIV had forty galleys, thirty-four of which were based in Marseilles. A regular galley required 260 rowers, that the courts were required to provide. However, Protestants were not sentenced to provide labour but in order to set an example and promote fear.

On the sentence registers which recorded 60,000 galley-rowers between 1680 and 1748, the 1550 “galley-rowers sentenced for their faith” made up only 4% of the total number.

The reasons for sentencing based on religious faith

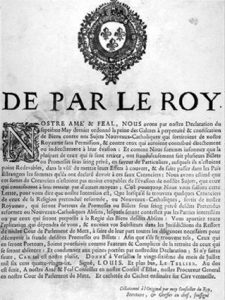

The 1685 Edict of Fontainebleau, or the Revoking of the Edict of Nantes, made provisions to sentence to the galleys those Protestants who attempted to leave the country or who publicly practised their faith in the banned Reformed Church .

Among those who were sentenced :

- 22% for leaving the country

- 53% for illegally gatherings of « Churches of the Desert »

- 11% for possession of firearms or gunpowder

- 1% for protecting or sheltering a pastor

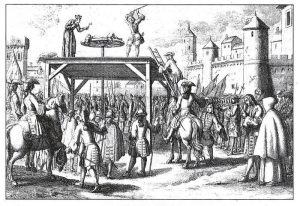

Very few pastors were sentenced to the galleys because they were generally sentenced to death instead.

The periods of pro-active persecution

Some periods of time saw a massive influx of Protestants : at the Revocation of course (1685), but also in 1690 when Louis XIV declared war on Protestant Europe (Augsburg union), in 1697 when the Ryswick Peace Treaty was signed and finally when the “Camisards” rebelled.

In one single day in Montpellier, Superintendent Baville sentenced to life imprisonment 75 men who had been to the Principality of Orange, a foreign enclave where the Reformed cult could still worship publicly.

In 1713, a large number of Protestants were released under repeated pressure from Queen Ann of England, provided they left the country.

Under Louis XV, 132 Protestants were still sent to the galleys, and around 50 after 1748 when the convict prisons replaced the galleys as a detention facility. The last two Protestant convicts, who had been forgotten, were finally released.

Life as a galley-rower

The rowers were kept tied to their bench twenty-four hours a day on the uncovered single deck of the galley, sitting on both sides of a gangway, at the end of a 12-metre long oar. Two teams rowed at the same time at a pace of twenty to twenty-five strokes a minute ; sails could sometimes be used instead to propel the boat.

They served at sea for roughly two to three months ; the rest of the time, the galleys remained in Marseilles ; a large number of the convicts were hired by the port craftsmen. They seldom escaped because a huge reward was promised in the event that they were caught. The others, who had remained on board, had to hand-make stockings.

The lot of Protestant galley-rowers

The life on board galleys was accurately described by Jean Marteilhe, a Protestant who was sentenced to the galleys in 1701 and released 12 years later, in a book : “Memoirs of a galley-rower at the service of the Sun King”. He showed how hard people tried to convert Protestants, who were subject to extra mistreatment and the most recalcitrant ones were kept in dark cells in Fort Saint-Nicolas in Marseilles. On board, the Protestants managed to organise support networks among themselves and with members outside, both in France and in the countries of Refuge in order to get financial support or letters to support them in their faith.

44% died in the Royal Hospital for Convicts in Marseilles (71% of deaths occurred within three years of sentencing). 56% were released, although 40% of them spent ten to thirty years on galleys.