Protestants and economic life

Soon after the Reformation, Protestants became involved in collective and public responsibilities with a significant impact on both university and economic life.

Protestant «men of action»

As from the XVIIIth century in Anglo-Saxon countries, and from end of the XIXth century in France, Protestants contributed to the modernisation of universities. An example of this was the introduction of technical education.

As far as economic life is concerned, they took a prominent part in the development of modern western industrial capitalism, “modern” because it was founded on a rational organization of work.

In France, the names of Oberkampf, Schlumberger, Peugeot, De Dietrich, Hottinguer, Odier, Bungener, Courvoisier, Mallet, Haviland, Vieljeux, Delamas became well-known : since the XVIIIth century these had been the great names contributing to the merchant navy and the shipbuilding industry (opposing the monarchy, they had hoped to take advantage of the profits by investing them in a naval fleet). Amongst them also, during the XIXth century, the names of a number textile manufacturers or the wool industry, managers of the fledgling steel industry, or of the merchant banks who, through their credit policies, were able to encourage significant industrial progress. Generally speaking, Protestants have been responsible for great industrial achievements in Germany, in the Netherlands, in England, where the industrial revolution had begun (the economist Adam Smith had studied theology), and of course, in the United States.

Does this imply that Protestants were particularly competent to develop such responsibilities, and that such competence was inseparable from an ascetic way of life necessary for the enactment of secular utilitarian doctrines still in force today – though in a more complex world where, to a certain extent, entrepreneurial capitalism has taken over ?

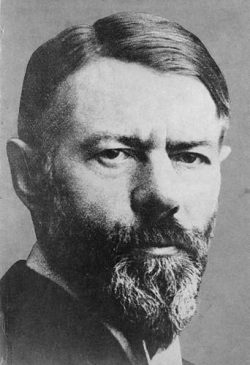

Max Weber's sociological theory

Such is the well-known theory expressed by the German sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920) in his work Protestant Ethics and the Spirit of Capitalism. Max Weber never claimed a relation of direct cause and effect between the Reformation and the industrial development of modern societies, but he did suggest the existence of a selective affinity between Protestantism and modern capitalism, an affinity closely linked to the new formulation of the nature of salvation proposed by the Reformation.

Neither did Max Weber claim that capitalism had its origins in the Reformation. Capitalism existed prior to the Reformation, but with more speculative, more adventurous, violent warlike characteristics.

The sociologist’s theory is primarily founded on a study of action analysed over a long period of time, from ancient Judaism (the beginnings of monotheism) until the early XXth century. He wrote at length about early indications of a desire for rational action in western monasteries and their asceticism away from the world.

Specific work ethics

The Reformation gave a new formulation to the doctrine of predestination, and with it asceticism became a requirement for life in the world and no longer for a secluded life only. Max Weber did not deal with the theological issue of predestination. He kept to certain interpretations of it, such as the notion of a divine decree or ordinance that determined, prior to a human being’s birth, what his salvation was to be.

Such an interpretation did mean, however, that the certitude of salvation could no longer be expressed in earthly terms, nor decreed by a human institution whose rules would have to be obeyed. In other words, eternal salvation is not acquired through works. On the other hand, signs of a confirmation of such an eventual election, though liable to be withdrawn, had to be sought by means of constantly re-evaluated labour.

It is, therefore, of the utmost importance to submit an action to prior reflection and to a concern for earthly ethics, so that the glory of God may be made manifest. The fruits of work are not a source of visible, personal glory. Nevertheless, Protestant ethics were undoubtedly close to those other-worldly ethics of work developed in western monasteries (and often very critical of the established Church). At any rate, it gave pride of place to the principles of rational action put into practice by the greater monastic orders.

Factors of economic success

From the start, all successful and influential Protestant enterprises adopted rational principles of reflection about the work to be undertaken. Such principles have been acknowledged as being instrumental to their success.

They were founded on :

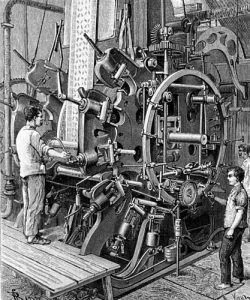

- a rational organization of work ;

- a rational system of book-keeping ;

- a rational search for worthwhile outlets ;

- a rational use of production tools, permanent attempts to improve them, and the encouragement of technical progress ;

- a clear-cut separation between industrial and personal ownership.

In this way such enterprises helped avoiding the violent upheavals of a long-existing speculative capitalism, and proved to be a great incentive to social development.

A method of organization that was to develop outside the Protestant world

Protestants being a minority in France, the success of their firms in France were often followed by alliances with Roman Catholics. Nevertheless, such alliances were realised only at a time when rational principles of economic development had become quite secular and were often based on utilitarian theories. The latter, though they had often been introduced by Protestants, had since become autonomous, and were to know other problems.

Associated tours

-

Protestants and economic life

Business and banking, though perfectly secular activities, have retained a durably specific connotation when carried out by Protestants.

Associated notes

-

The Peugeot family

Since the XVIIth century, the Peugeot family – a Lutheran family from the Montbéliard district – has contributed to the economic growth and social development of France by building an industrial empire... -

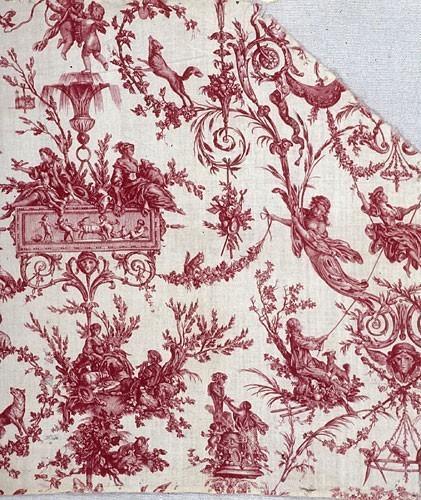

Printed fabrics in Jouy-en-Josas (1762-1843)

In 1762, Christophe-Philippe Oberkampf established a cotton printing factory in Jouy-en-Josas (Yvelines) ; it was to become very well-known. He succeeded in keeping the factory working throughout the whole French Revolution.... -

The De Dietrich factories

-

Frédéric Engel-Dollfus (1818-1883)

Frédéric Engel-Dollfus was a protestant and a textile industrialist concerned about conditions for the working class.